Most major cities in Japan were left in ruins after the second world war, in particular, Nagasaki and Hiroshima. In the post-atomic bomb area, Japan was democratized and turned into a nation with a pro-American orientation. As a response to the human and environmental catastrophe, and as with the growth of the Japanese economy in the early 1950s, proposals for urban redevelopment began to appear. This is when the first concrete example of urban planning with ideas that would later come to define the metabolism movement appeared. You can argue that it started with the designing of the reconstruction of Hiroshima. The Japanese architect Kenzo Tange and his team of architects was commissioned to make this plan.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum / Kenzo Tange. The initial plan was presented in 1949 and the building was made in 1955. source: "Hiroshima mon amour [1959]"

In the 50’s Kenzo Tange was very oriented towards the international architecture scene, note the resemblances between the memorial building and the work of Le Corbusier. He also met up with and found inspiration in an architect such as Aldo Van Eyck who was in many ways in opposition to the “functionalism” of Corbusier that was criticized of ignoring its inhabitants. Van Eyck created the orphanage next to our school, and took part in coining the architectural movement structuralism that Tange also defined himself within.

Orphanage / Aldo Van Eyck build in 1960. source

In short you can say that they shared some of the same ideas in creating spaces where the relationships between the elements are more important than the elements themselves – built structures corresponding to social structures. It wasn’t until 1960 that the movement was actually defined, by the architect Kiyonori Kikutake who created their first manifesto together with the architect Fumihiko Maki and Kisho Kurokawa:

“Metabolism 1960 : The proposals for a new urbanism ”.

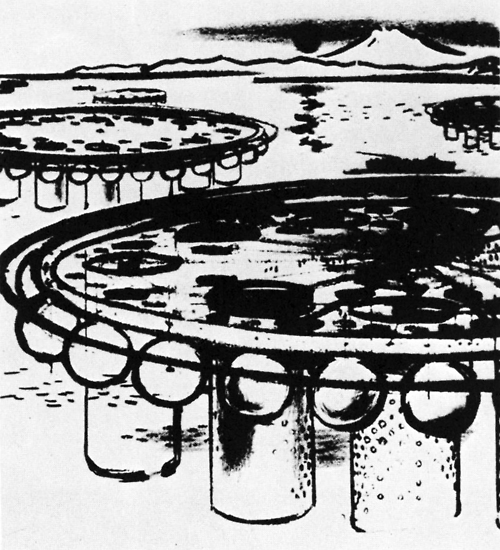

The name arrived to an other member of the movement, Kionory Kikutake, as he was working on a floating metropolis, his “Marine City” project.

Marine City / Kiyonori Kikutake 1958. source

The word “Metabolism” comes from Greek and translates to “change” but also refers to the life-sustaining transformations within the cells of living organisms. As the name might suggest? they pushed that buildings and cities should be designed in the same organic way that life grows and changes by repeating metabolism.

The “Marine City” is one of many projects that was never realized but played a central role in the works of the Metabolists. It was this vanguard idea of taking on new space whether it be the ocean or the sky that was the foundation of their way of shaping “the future”. At the same time it required developing and making use of new technology. None of the experiments and realizations were made by single individuals but drew on the big think-tank that the Metabolist movement was from artists and writers to scientists and industrial designers. The “marine city” was a proposal for a solution to the rapid population boom especially taking place in Tokyo in the years after the war till the brink of the 60s. Kikutake believed that the ocean was the only valid space to develop in times of an imbalance between population and agricultural productivity.

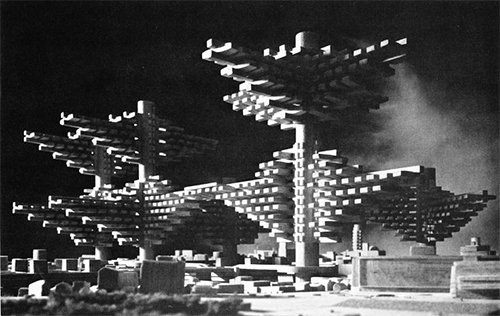

City in the air / Arata Isozaki 1961. Never realized.

As such sustainability was surely an integral part of this movement as well as resilience considering how the risk of earthquakes and tsunamis make for tough conditions in japan – especially for urban concentrations. Structure wise the Metabolist movement was characterized by taking certain architectural steps towards recognizing this. A main idea was to design architecture to be built around “spine-like” infrastructure on and around which pre-fabricated replaceable parts could be attached being almost cell-like. At the heart of this setup is also reorganization of the relationship between society and the individual.

Another important inspirational source was found in old Japanese shinto religion and a specific Ise Grand Shrine that carries the ritual of being created anew every 20 years. This is an example of how the Metabolists as a movement was wearing multiple meanings, being both modernists and traditionalists at the same time.

Ise Shrine having been in continual existence since 690 C.E. source

The Metabolists respected environmentally-conscious boundaries and the material in which they worked. This gave them the pride, and also reluctance, to not be parted from their vision. To demonstrate and construct only that of ideas was monumental enough.

Festival Plaza / Kenzo Tange and the artist Taro Okamoto, Osaka Expo, 1970. source

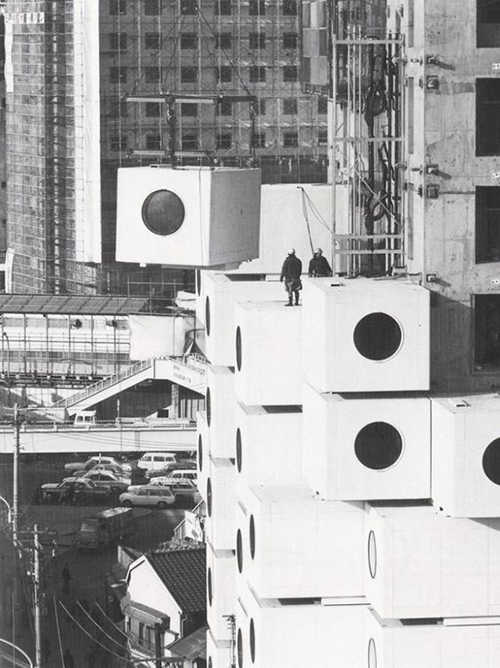

After 10 years of development and growth within the Metabolist Movement, the structure that was metabolism came to a climax, exhibiting some of their finest work, at Expo 70’ in Osaka, Japan. It was around this time that Kisho Kurokawa’s project, The Nakagin Capsule Tower, began construction. A process that took only 30 days to complete.

Nakagin Capsule Tower / Kisho Kurokawa 1972.

This building would serve as an “icon” to the movement. After the Expo 70’ took place in Osaka, individual architects from the movement began to take a step forward personally, focusing more on individualism and self-driven growth. Ideas about sustainable development within the 21st century are not new ideas; they have spread through a continuous evolution. An end sometimes not only existing as an end, but that of a new beginning.

text by Christian Stender and Ivan Fucich