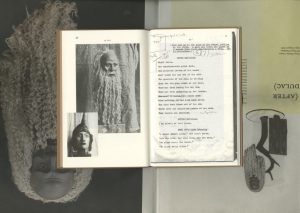

ARTISTS' COCKTAILS by Ryan Gander

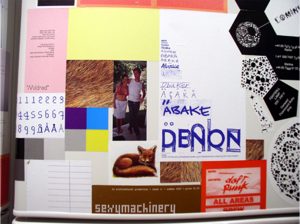

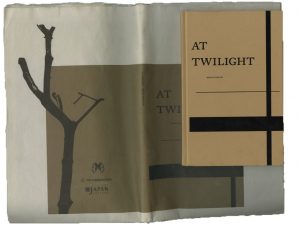

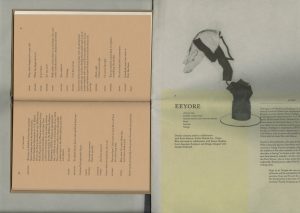

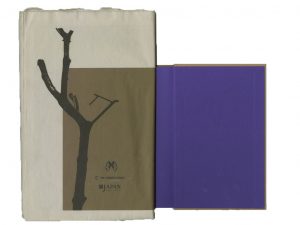

This small and light book is bounded with a hard cover, but also covered with a soft non-glossy finished paper so that it gives you a soft touchiness. Before you open the book, you can see the side of the paper has colored yellow, orange and fluorescent pink as you can see the same layers on the book cover. As the book has the theme of a cocktail, when the book is opened, the layered colors from both sides of the paper surround the text as the color spreads in the glass like a cocktail. Fun. In the text, the shape of the little letter ‘g’ seemed to simulate a water droplet. A fluorescent pink color was used was used to accentuate parts of the text. If you look into the images, you will notice that those are all different in size, layout and content, but the contents are all corresponded to the cocktail recipes introduced later. These layouts allow me to cross the front and back of the book and engage me to participate more actively.

This book was designed by Åbäke with Delphine Bourit. On the back cover of the book has the names of more people who participated, and for the first, there is Åbäke. Åbäke. Åbäke.

Who then is Åbäke?

Åbäke is a London-based collective of four graphic designers. Patrick Lacey from the UK, Kajsa Ståhl from Sweden, Benjamin Reichen and Maki Suzuki from France. They have been working together since 2000 after studying at Royal College of Art in London.

If you know Swedish language then you would smile at the name of the studio, because it means ‘clumsy’ in Swedish, but it also has the meaning of ‘ghost’ in Japanese language.

They have worked on magazine Sexymachinery(2000–2008), restaurant Trattoria(2003), the publishing project Dent-De-Leone(2009), the propaganda Victoria & AlferD Museum(2010) and so on.

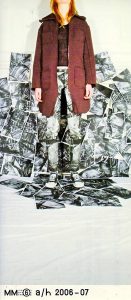

© Shift [left] © Maison Martin Margiela / Åbäke[right]

Active since 2000, they have collaborated with many Galleries and with fashion designers such as Hussein Chalayan and Maison Martin Margiela, artists such as Ryan Gander, Johanna Billing, and bands such as Daft Punk. If you search more about them, you will find out that they are the co-founder of Kitsuné.

Kitsuné is well known as ‘Maison Kitsuné’, which is French fashion label. Åbäke established Kitsuné in 2001 with Masaya Kuroki and Gildas Loaëc.

Masaya Kuroki and Gildas Loaëc © Maison Kitsuné

At the beginning, Kitsuné was French electronic music record label. Gildas Loaëc is French DJ who was the manager and art director of Daft Punk. He met Japanese-French designer Masaya Kuroki when he went to watch ’interstellar 5555 (Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem – produced by Daft Punk, Cédric Hervet and Emmanuel de Buretel with Toei Animation under the supervision of Leiji Matsumoto)’. They found their common interest and made the label together with Åbäke.

Kitsuné, which already has a large fan base in Europe and the U.S., begun to be recognized as a fashion label in 2005, showing their first fashion collection and the mixed album ‘Compilation Kitsuné Maison 1’ at the same time at ‘Palais de Tokyo’, one of the famous museums in Paris.

Following the website of Maison Kitsuné, “Maison” is the French word for “house”, and “Kitsuné” is the Japanese word for “fox”, a symbol of versatility.

Fox symbol logo of Maison Kitsuné © Maison Kitsuné

As the fox possesses the power to change its appearance in the Legend, Maison Kitsuné always has been tried to adapt its repertoire according to inspiration. The philosophy that Maison Kitsune pursues is that they try to change their material and style freely according to their inspiration, as their name suggests, it is quite similar to what Åbäke is doing.

If you follow the steps of Åbäke, then you will see much of their projects were coming together with concentrations on the social aspect and the collaboration. Their events usually comes with different sources like film, dancing, eating and cooking and teaching. They are also singers, painters, photographers, members of bands, furniture designers, curators, fashion designers, DJs and teachers. These are also happening at Kitsuné. They are usually coming up with collaborations between different fields as well.

Just as Åbäke runs many workshops with students along with their own projects, Kitsuné is creating their own thing while also discovering and growing artists. Further more, as Åbäke collaborates with agencies and artists, Kitsuné is also performing collaboration with artists and fashion labels. Although their fields are not quite the same, it is clear that they inspire each other.

In the interview with Japan-based international online magazine ‘Shift’, In 2003, Åbäke said that with Kitsuné they are able, because of their different fields of knowledge, to work in music, clothes and events.

I seem that it is important to talk about Kitsuné when I looked at Åbäke because they have different shapes, but same steps to each other. I am still waiting for the reply from Åbäke that I asked about Kitsuné, but I think there is no doubt that this one big galaxy -Kitsuné- is definitely the greatest cocktail of Åbäke.

Ryan Gander: Artists' Coctail. designed by Åbäke, Rietveld library number: gand 5