The American-born French artist William Klein (1928) is a multifaceted photographer and filmmaker, known for an unconventional style of abstract photography and in the same media a revolutionary approach to fashion. This text, however, focuses on his series of photo books portraying the cities New York, Rome, and Moscow.

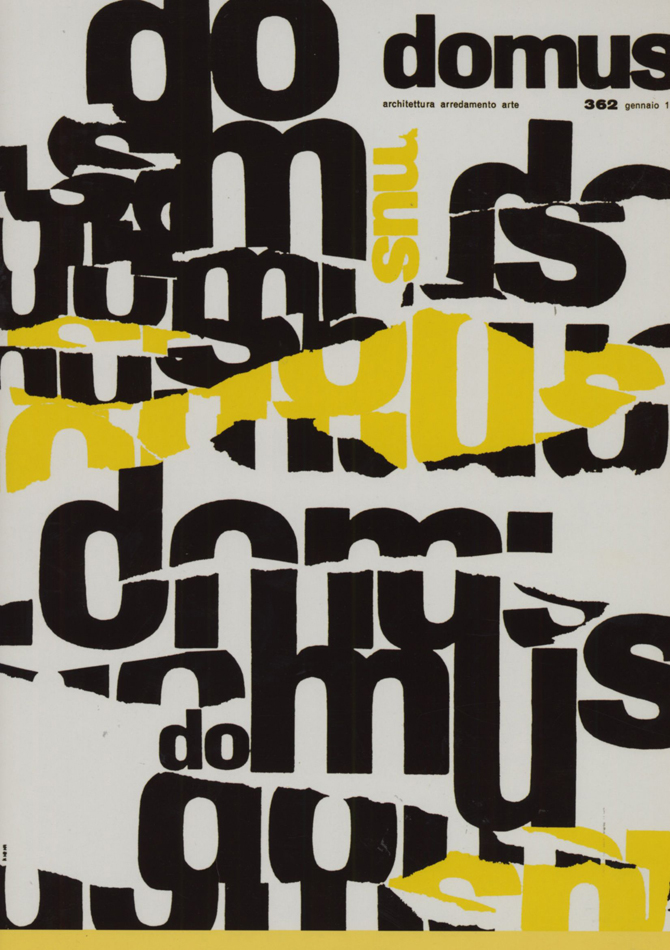

This research had its starting point in Klein’s posters for the magazine Domus; As elaborated later in the text, Klein experimented to a great extend with a sort of “trashy”, or maybe just honest, way of expressing “city life”. Domus began to publish Klein’s experimental graphics/photography as front covers for the magazine in 1952. Among the covers were a very rough way of handling photography and typography to be seen: William Klein would torn his own work apart and put the ripped parts back together in an uncouth order. As a visual language this lack of perfection and polished finish seems to find its inspiration in the actual torn posters one sees on walls in the streets of big cities. Having this style of “torn” magazine covers in mind, this research dives deeper into Klein’s visual language [x] describing the life of a city.

Klein studied painting and never received formal training in photography. One can argue that this “lack of technical education” made his experimental approach to the media possible. He would have to find his own way. This experimental and playful way of working with a medium is also present in Klein’s graphic work, as for instance seen in various posters, where Klein mixes photography, painting, collage, and typography.

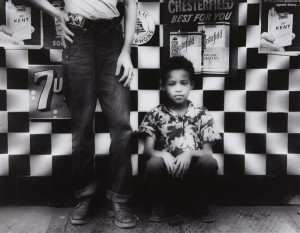

His lack of academic photography training also showed itself as a virtue in his genre-defining photo books portraying cities that Klein visited. The first one, “New York” started as a photographic diary. When Klein came back to his hometown after six years of studying in Paris, he found momentum in this medium, that he had never really used before, and executed the extensive series in just 3 months. It was also a reflection of him returning to the streets he walked growing up and seeing new representations of people and situations he experienced there. The blurry, close up, in the actual photographs where not popular at the publishing houses but eventually broke through and had a huge influence on what we know as street photography. The next book, “Rome”, was made shortly after Klein moved there to be an assistant to Fellini.

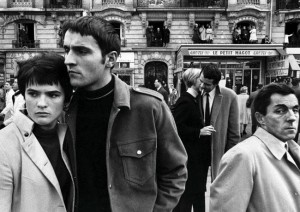

left: image from 'Rome'©59 / right: image from 'Life Is Good and Good For You In New York'©56

Having two very separate relationships to the two cities must have affected the way Klein approached the photographic investigation. With this background in mind, you can distinguish some differences in these portraits. “New York” contains more pictures of children, a way for him as the protagonist to relate back to his past experiences in the space. He even says in an interview that he sees many “self-portraits” in the series. While “Rome” has similar stylistic features, you can glimpse more of an outside view, even in the way people look back at the camera.

One strong characteristic that separated William Klein from the start and became one of his signatures, was the use of motion and blur causing blur. This expression was developed in Paris when he was trying to document a mural he had painted. The wall consisted of a row of rotating panels, that when captured on an image created geometrical shapes with obscure lines. This discovery would be very crucial to several of the branching that his practice took, but would not be well received initially by traditionalists.

When Klein originally tried to publish ”New York” it was perceived as being ”too ugly, too seedy, too one-sided”. The publishers were used to, and wanted to, see the city portrayed in a romantic light. The high class, the architecture, the richness. Klein’s approach was instead semi-aggressive, unpretentious, focused on the people, and had no interest in being a promotional tool. This, for the time, controversial viewpoint would, however, be very welcome when he made the ”Moscow” book, the third in the series. The western/American picture of Russia was (and still is, but maybe even more extreme back then) extremely alienating and one-sided. His book depicts a lively and multifaceted Moscow and is considered to be the book in the city series where he comes closest to the subjects.

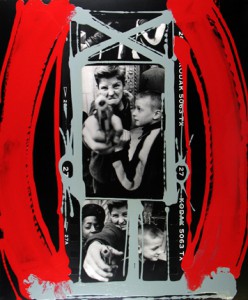

Sarah Boxer wrote a review in 2001 in New York Times [x] of two of his shows, where she brings up the notion that the authenticity in Klein’s pictures might be partially staged. Specifically, she talked about an exhibition where his contact sheets are being magnified and displayed. The contact sheets had notes in the shape of circles, arrows, and crosses, singling out the pictures that Klein had chosen to use when he originally developed the film. What made her questioning was the decoratively ”perfect” manner in which the lines were made. A lot can be said about this. Klein was originally a painter, so that could be an explanation for the way the motions of his hand could come of as decorative by default. Anyhow, it is interesting because much of his legacy, and the tradition of street photography in general, is built on the purity and honesty of the content. Though some of his works are known to be staged, it still has proved itself to be able to catch an essence in a community in a superior way.

A general problem in culture is the inevitable tendency for rebellion to become stagnant. As a direct consequence of success and the finding of a language that comes with age, groundbreaking eventually becomes mannerisms. Klein has been lucky to keep a youthfulness about his work, often by sporadically changing lanes and looking for limits to cross in another niche. This quality has made him a prominent figure in a variety of photographic disciplines and testifies the importance of diversity that the market often overlooks.