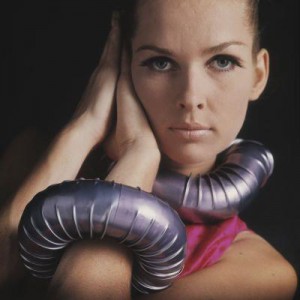

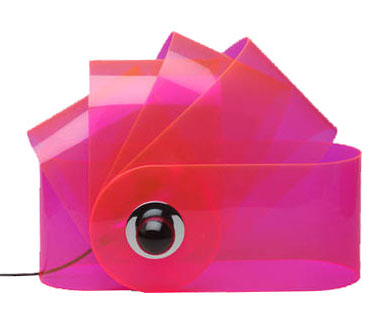

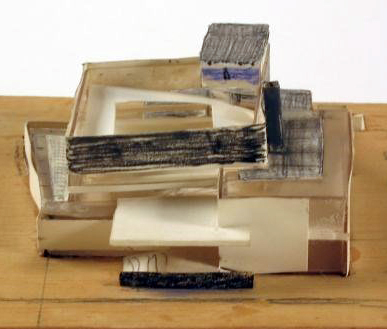

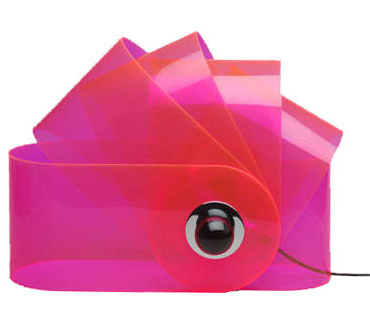

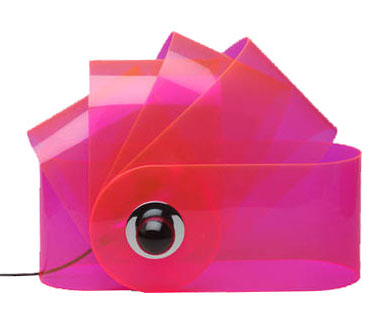

Gherpe – a lamp designed by Superstudio

(via:http://www.nova68.com/gherpelamp.html)

I think the Gherpe lamp is a relevant design because of several reasons. First of all, the lamp itself is made of materials that are still considered modern, even though it was designed more then forty years ago. That alone already shows how we still hang on to, or maybe are condemned to these materials nowadays. Next to that is the design, which references to the mathematics that appear in Nautilus shells. Then again the way this shape is interpreted is more like a cartoon of it, leaving the classical Nautilus image behind. This way of designing, letting interests and research – the designer was into marine biology – influence the work is something I think many designers work like, or would like to work like. Last reason why I think this is a relevant piece is because I think the whole of Superstudio, their designs and mainly their architecture is, because of their new views and extensive researches, relevant. They were part of a critical wave, commenting on Florence and it’s ancient heritage, on the years of full trust in technology and on architects before them. They wanted designers to be responsible for their creations when they design to make a better world. Their criticality on how design and architecture influences the life of other people and self-reflectiveness is what made them different from many before them. This idealism in theories, but with playfulness towards the designing process itself is to my opinion something important to keep relevant in art and design.

(via:http://photografieundmehr.com/pics/2012-11/gherpe_01.jpg)

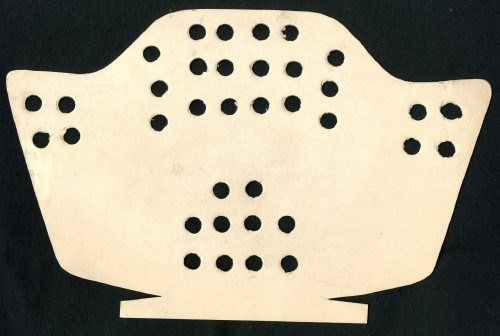

Nautilus shell

(via: http://www.hungrywalrus.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Nautilus-POS.jpg)

To test it’s relevance I’ m trying to get to know what Gherpe is, what it is not and what it could be, what it means to Superstudio and what it means to me.

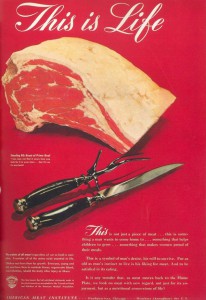

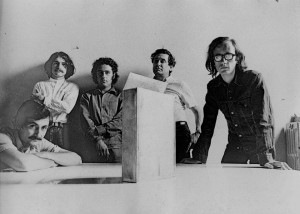

At a time where popular culture is stealing all the science and logic that Modernism employed to make this world better, with youngsters starting to call themselves Mod.’s, Pop Art commenting on this Modernist reality and society by reproducing imagery from that popular culture, Gherpe is born. It’s designed by Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, and adopted by Superstudio, the Italian architecture group where Toraldo is the most important member of, together with Adolfo Natalini, who is a Pop Art painter when they found the group in 1966.

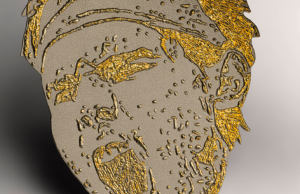

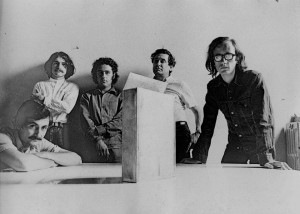

Alessandro Magris, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Piero Frassinelli, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini

(via:http://www.domusweb.it/content/dam/domusweb/en/from-the-archive/2012/02/11/superstudio-projects-and-thoughts/big_374062_2176_giulia_superstudio3.jpg)

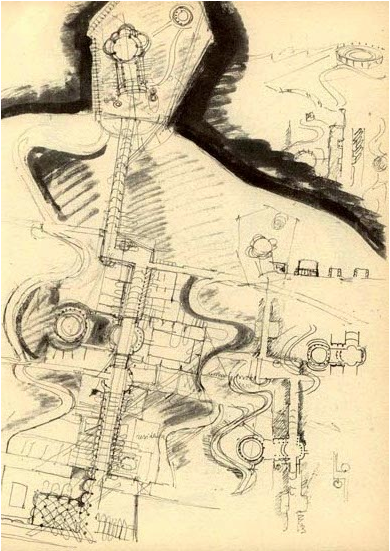

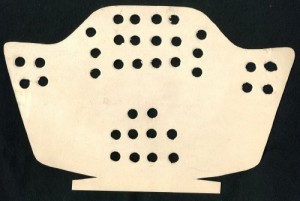

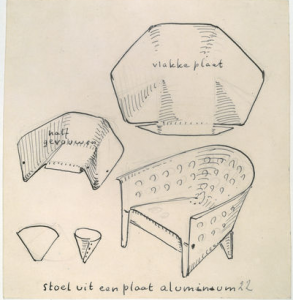

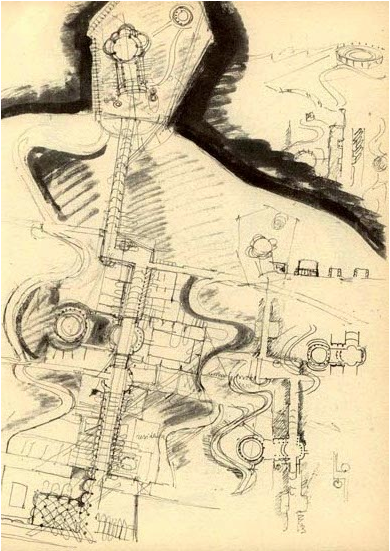

Where Modernism, in its affirmation of the human power to improve their environment the aid of practical experimentation and science, goes for logic, Gherpe pretty much mocks Modernism, by taking it’s science and it’s new materials to make something that is not in any way useful other than it’s aesthetical purpose. Gherpe is not practical, and it’s not helpful. But Gherpe’s cartoon like ambiguity looks fun, you want to have it, it looks smart even though it isn’t, and that’s exactly in line with popular culture of that day. Gherpes connection with nature is meaningless, but very important for it’s attractiveness. You could say it’s a beauty trick. The interest of Superstudio in nature combined with construction is to be traced back to one of their guides in the Academy of Architecture in Florence, which most members of Superstudio were attending. His name was Leonardo Savioli. As Adolfo Natalini says about Savioli: “Even when the drawings looked like traces of insects or explosions, galaxies, spiderwebs or wounds, they were always able to resemble parts of constructions or something constructable”.

Plate XVIII, a drawing by Savioli

(via:www.etsavega.net/dibex/Savioli_citta-e.htm)

The fact that Gherpe’s reference to nature doesn’t have any symbolism or engagement in it, already shows what things it really has to do with, things like freedom. Gherpe is free from the morals that come with modernism: Superstudio didn’t think architecture could change the world for the better. Gherpe is the joyous realization that the burden of creating something that will add to create paradise on earth is not possible.

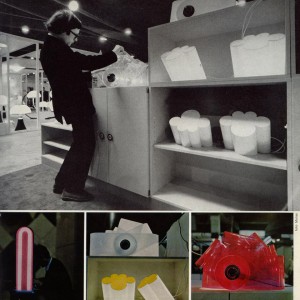

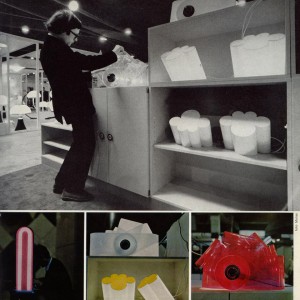

Gherpe was in the Superarchitettura show. This was a show combining two groups. The Superstudio and Archizoom, both from Florence and mainly from the same architecture school. The show took place right after a flood had swallowed a chunk of Florence’s renaissance beauty, at a time where others mourned renaissance architectures birthplace the Superstudio show was a psychedelic experience work that purposely lacked engagement and put consumerism on a pedestal. Their ideal: morals were irrelevant to architecture, and so you should not aim to change the world with it either. So there is a different approach: “Superarchittettura accepts the logic of production and consumption, it utilizes it in an attempt at demystification” and “Superarchitecture is the architecture of superproduction, of superconsumption, of superinduction of superconsumption, of the supermarket, of the superman, of the super gasoline”.

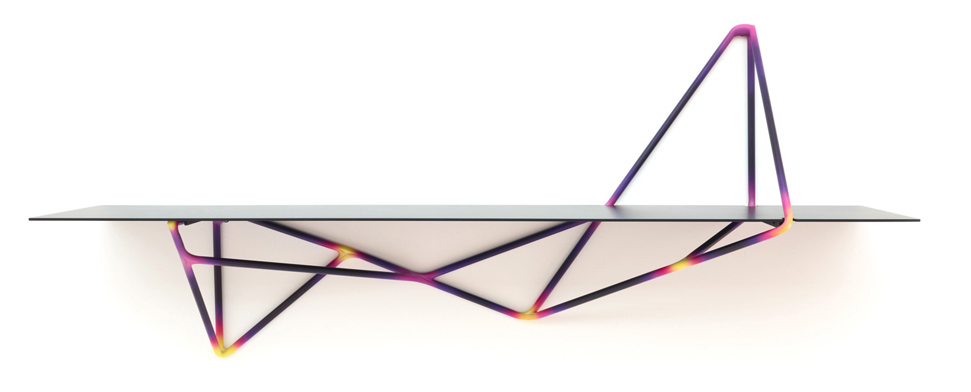

Toraldo and Gherpe, and Passiflora

(via:http://www.centrostudipoltronova.it/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/gherpe-archivio2.jpg)

Seeing Gherpe from the eye of the Superarchitecture that it is, means not that Gherpe was meant for a world better than ours, but for the world as it was in 1967, where consumption and production were exploding. You could say, Gherpe is super itself. A lamp fitting for all these phenomena that felt relevant for the younger generation at this time. Instead of denying these phenomena, or wanting to change them, Superstudio designed something that fit in. It might even accelerate superconsumption, be meant for that purpose. In this perspective Gherpe is in a way a neo-futuristic piece, a monument for the speed and mass of its time. You could also see Gherpe as an, perhaps slightly melancholic, attempt at creating something, something touchable and real out of all the superlatives that together form the ungraspable frightening dystopia that was (and is) everyday life. And maybe that this is the reason we enjoy it, because Gherpe is then our comfort, a sign that from superproduction and superconsumption something appreciable can materialize.

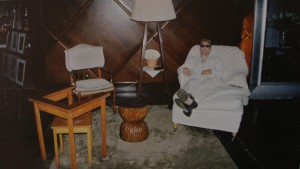

Image of Superarchittettura show

(via:http://www.stylepark.com/en/news/a-landscape-of-mountains-and-valleys-the-design-parade-03-in-hyeres/283330)

Gherpe shows Superstudio’s double nature: it’s serious, socially critical but can also be ironic. When Superstudio presents an utopian, or dystopian design we can never accept it at face value. When they design a utopia, they explore every possibility into the extreme, and so exploration of the architecture itself is it’s aim. Instead of presenting the possible solutions it tells the stories of the decisions of mankind, the ones it made and might make. A very serious and melancholic subject, reflecting their serious opinions (Adolfo Natalini: “the race of consumerism is definitely wrong”) but enabling playful and smart experimentations.

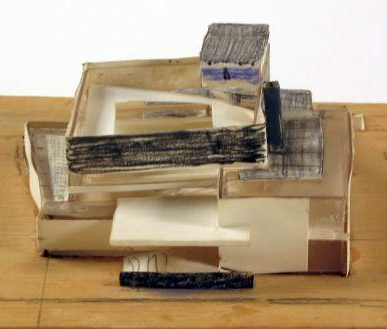

As Gherpe is an early Superstudio piece, Gherpe is also an early exploration which, as we can see in the Stedelijk, ended in a lamp. As Superstudio kept exploring their ideas became more and more critical of architecture and design, which made their projects end up way less often in actual designs and realizable architecture. Instead they expressed their ideas in movies, models and collages.

According to Superstudio architecture was corrupted to such an extent that even the avant-garde architect was guilty of suppressing human development, since he made use of existing conventions in architecture. An interesting idea, which suggests human development can come from no other place than out of the blue. Where one can ask the question what human development actually is, but let’s get back to Superstudio. They saw reason as the only quality that’s uncorrupted by these conventions. This makes it’s easy to see why they step farther away from architecture and design, as they are easily seen as complete and valid evidence of manifestos or ideas, rather than generally questioning and alienating. That doesn’t mean Superstudio didn’t make anything at all anymore, as you might expect.

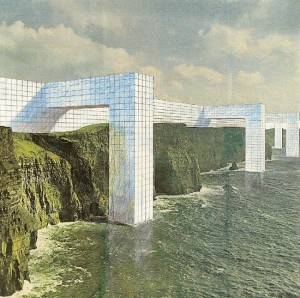

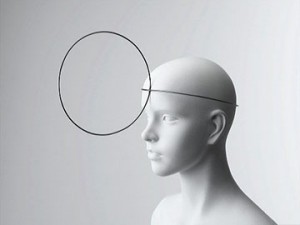

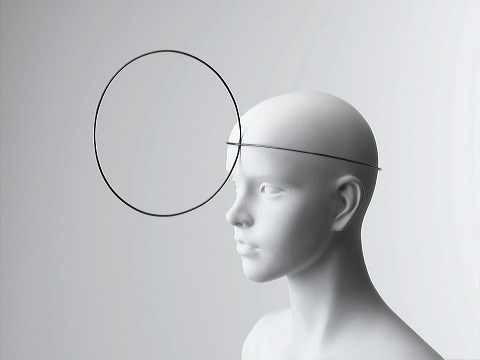

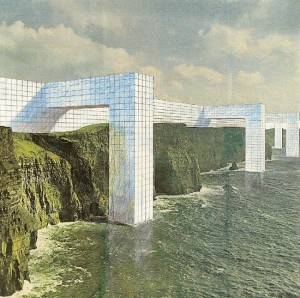

Instead they found ways to visualize what architecture could be, without designing from conventions. Something that wasn’t really architecture. For the exhibition “ Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” in the MOMA Superstudio made an 8 x 8 black square on the floor, and made it repeat itself in an endless grid by placing mirrors at the walls. They put a box with wires on each corner, making the plugs recur regularly in this “landscape” [x]. It wasn’t the first time they worked with this black grid [x], but it was the first time architecture and design was so completely dismissed that it was actually left out at all. Even though this seems like the ultimate conclusion, there’s more to the ever expanding black grid. In the Continuous Monument, a glass grid-like structure that spans all over the world, visualized in absurd collages [x] where it embraces Manhattan or faces the Taj Mahal, the irony, social critic and dystopia remains: a homogenous unrealizable blank space, but also a space where we can project our own ideas on of what it really is. Our ideas, full of conventions and corruption.

Grid in the Moma: View of Supersurface: An Alternate Model of Life on Earth, by Superstudio, in Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, MoMA, 1972. Photo: Copyright Cristiano Toraldo di Francia.

(via: http://www.archdaily.com/421040/environments-and-counter-environments-italy-the-new-domestic-landscape-moma-1972-exhibition/)

As you understand now, Gherpe too is a piece of corruption. A mash up of conventions and brainwashing, which will, as you look at it, only corrupt and brainwash you more. Which is very true in the sense that, the more you know, the more you are stuck in the things that already are. Whether that really suppresses the development of humanity is questionable. I personally am less negative about the influences of the past and the conventions we get taught. But the fact that Superstudio deals so productively with their frustrations over a system is something everyone, defenitely every art student, can be inspired by.

Over thinking and commenting on how design works is something I find fundamentally important, as I think this self reflection is what can bring us to new insights. Insights that can be reflected on again later, a continuous process I’d say would be human development rather than corruption. But, if you are reading this, and you do happen to find yourself having been corrupted by looking at Gherpe and reading about it, then at least we can be sure about it’s relevance for the (design) world today.

The Continuous Monument, one of the many collages.

(via: http://www.spaceinvading.com/bookmarklet/Images/2701091233096716superstudio_monument_1_kl.jpg)