In the Booijmans exhibition ‘Setting the Scene’ both a work of Joep van Lieshout and Bas Jan Ader are shown next to each other in the theme room System. Does it make sense to combine these artists and to place them in this category? We try to answer this question by looking at the oeuvre of both artists.

JOEP VAN LIESHOUT

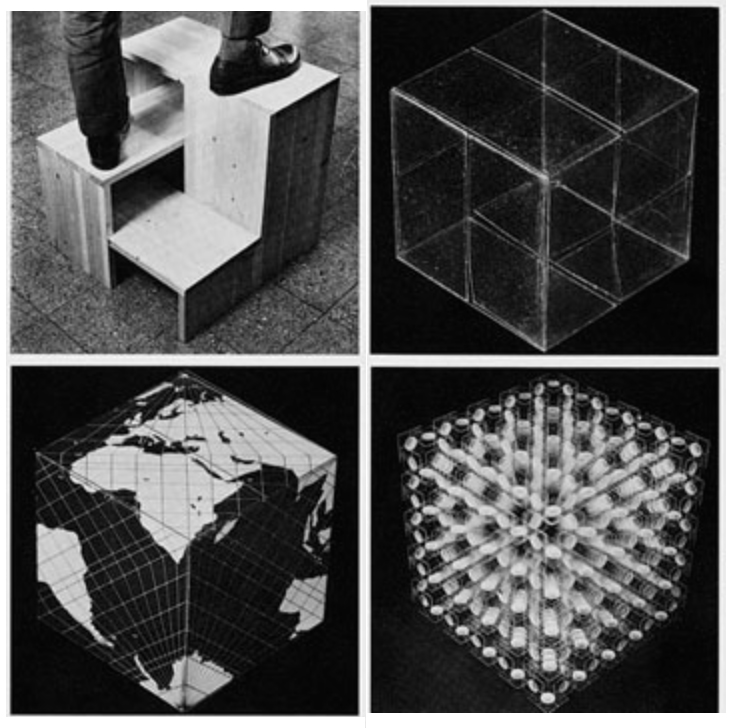

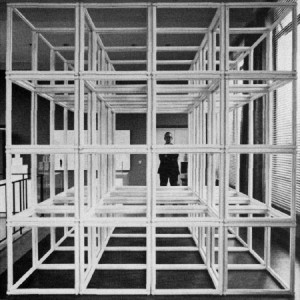

The work of van Lieshout that is shown in the exhibition is 12 crates, 12 stones. By ‘accident’ van Lieshout found out that they exactly fit together. But this is not all that random, because almost everything around us is build according to a system of standard measurements.

But 12 crates, 12 stones is not really representative for the work of Van Lieshout, aesthetically it looks like an outsider. He does however frequently use the notion of System in his work, but rather in the sense of human systems.

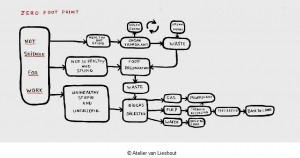

A good example is his work slave city (2005-2008). In the concept for this city, van Lieshout developed a system to re-use human bodies. The inhabitants that are not suitable for work can be recycled.

Next to this conceptual approach van Lieshout makes a lot of visual work showing the human system. In his organ sculpture series he took parts of this inner system outside of the body in a big and stylised form.

He also took the shape of organs into design and architecture. A great example is the CasAnus, a giant sculptural enlargement of the digestion system. The inside contains everything that a comfortable hotel room has, and for 120 euros you can spend the night in it.

If I reflect his work, I would say that Van Lieshout uses the human body system in two major ways. Both provocative (showing the inside, using body as flesh, focus on genitals) and functional (recycling, using shapes for design).

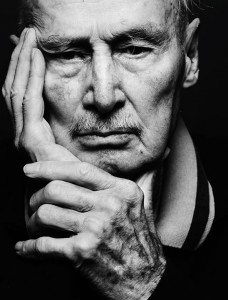

BAS JAN ADER

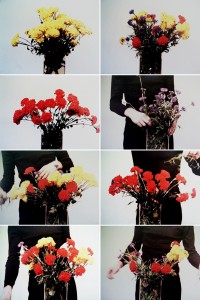

Bas Jan Ader’s work Primary time is also shown in the the room System as wel. The connection to this video with the theme is just as Van Lieshouts’s 12 crates 12 stones- totally obvious: a bouqetue of flowers are variously arranged by variating colour.

But is Bas jan Aders further ouvre related to this theme as wel or is it just this specific work that fits in? On fitst hand I tought the last example was trough. But when I made a small investigation on his work I saw it was very accurate to place him in the room “system”. When you look at the whole ouvre of Bas Jan Ader you can recognise a certain struggle with the system. For example in the “fall” serie”. He falls from a roof, from a bike, from a brach, etc. He puts himself in situations where the fall is ineveteble, the gravity wil win overpower anyway. In this work he is dealing with the rules of gravity: a deadlocked system. He reveals in a metaphorical way how this system is overpowering us.

The work “PietNiet” shows Mondriaan-alike paintings with no horizontal & vertical lines but only diagonal lines, with letters in them forming the statement “piet niet” (what means “no piet”). Also in this work you can recognise this urge to uncover a system, in this case more related to the artworld.

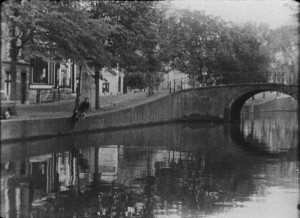

In his famous and fatal last work “in search of the miraculous” he tried to cross the ocean in a little boat. This failed and he died somewhere on the the atlantic sea. It’s very clear that he challenging mortality here; the ultimate system that we all obey. Bas Jan Ader as a filibuster who used poetic metaphors who that the attempt to bring down every system, even if its doomed to fail, and maybe even, especially because its doomed to fail.

CONCLUSION

Bas Jan Ader and Joep van Lieshout both deal with systems in their work. At van Lieshout work this is more a fascination; he isolates and enlarges certain systems in a -often humoristic- visual language. To play around and to investigate them. Bas Jan Ader is more challenging the system, he tries to break them down, what gives a more philosophical note to his work. And maybe, because all his attemps fail, you can even call it romantic.

On the other hand is there also a big thing these artist might have in common; an awareness of how many systems are dictating us. Bas Jan Ader plays around with the systems of life itself, Joep van Lieshout is finding this challange maybe more in the artworld. He breaks the distuigishment between art en design and he makes it inpossible for the vieuwer to put a stamp on his work. Maybe smart from van Lieshout to find this chalange in the art world and not in the real world, because – as Bas Jan Ader showed – playing around with the systems of real life can be fatal.