… and as I grab you and pull you closer to me, to get a better look of you, to face you, I feel instant disgust.

Disgust.

Maybe that is too strong of a word. It’s not like the look of you make me want to let go of you, not immediately.

Discomfort. The opposite of comfort. Suits quite well.

Dis-comfort. Dis-com-fort.

So, we stand here, face to face. I don’t even try to hide my feeling of discomfort. Don’t have to.

Look at you.

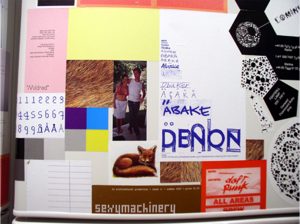

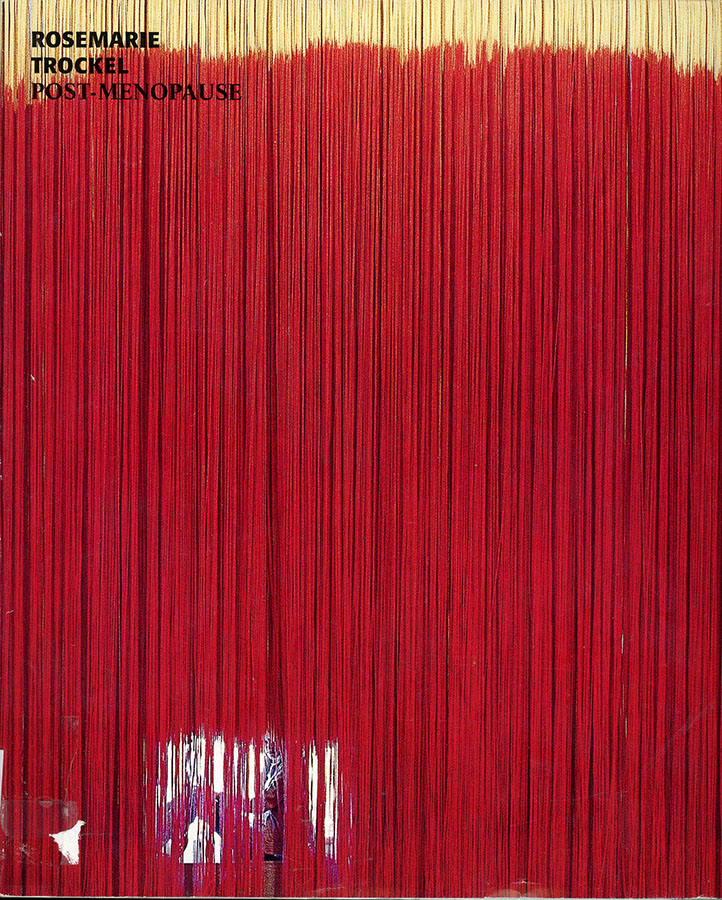

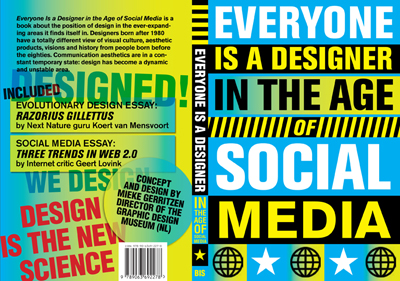

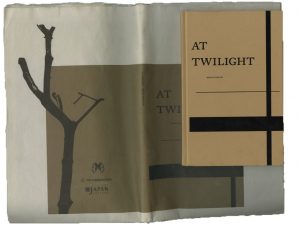

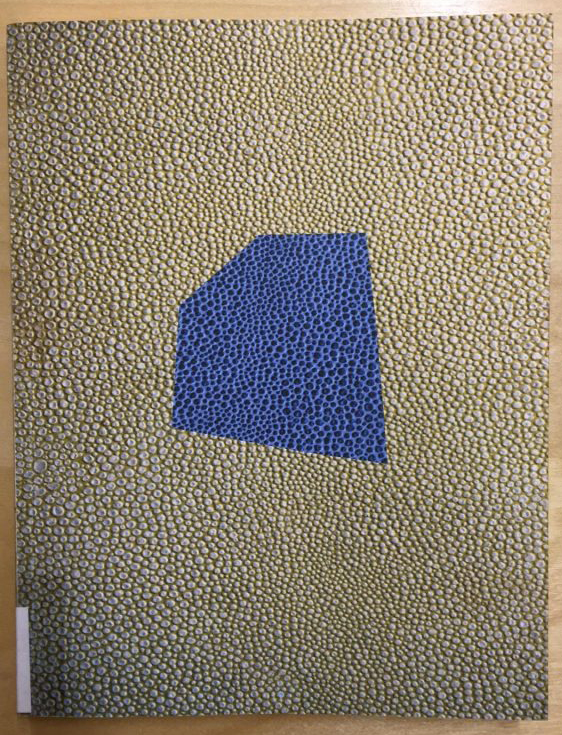

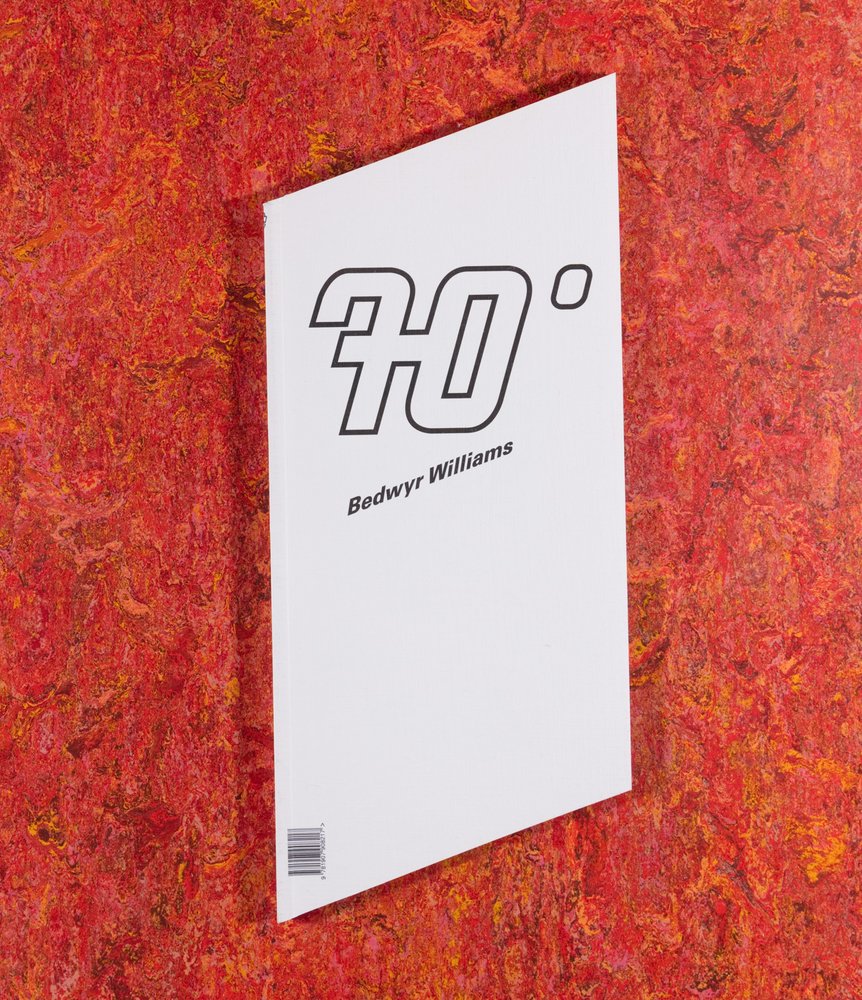

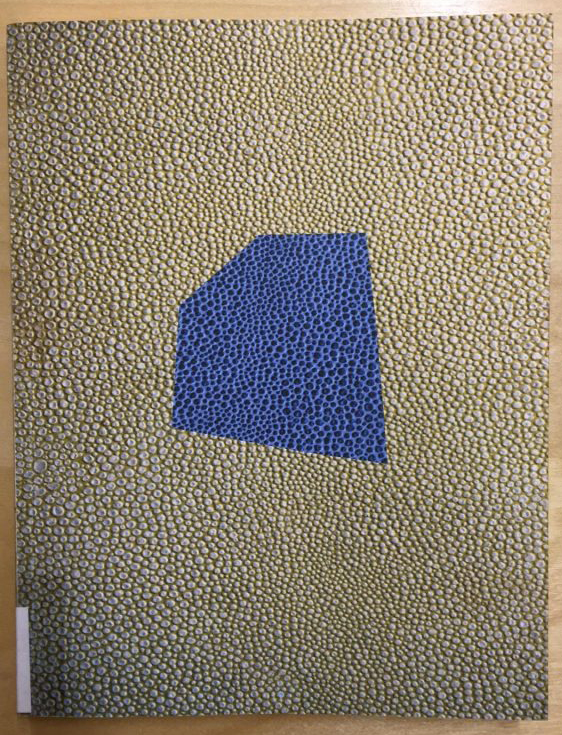

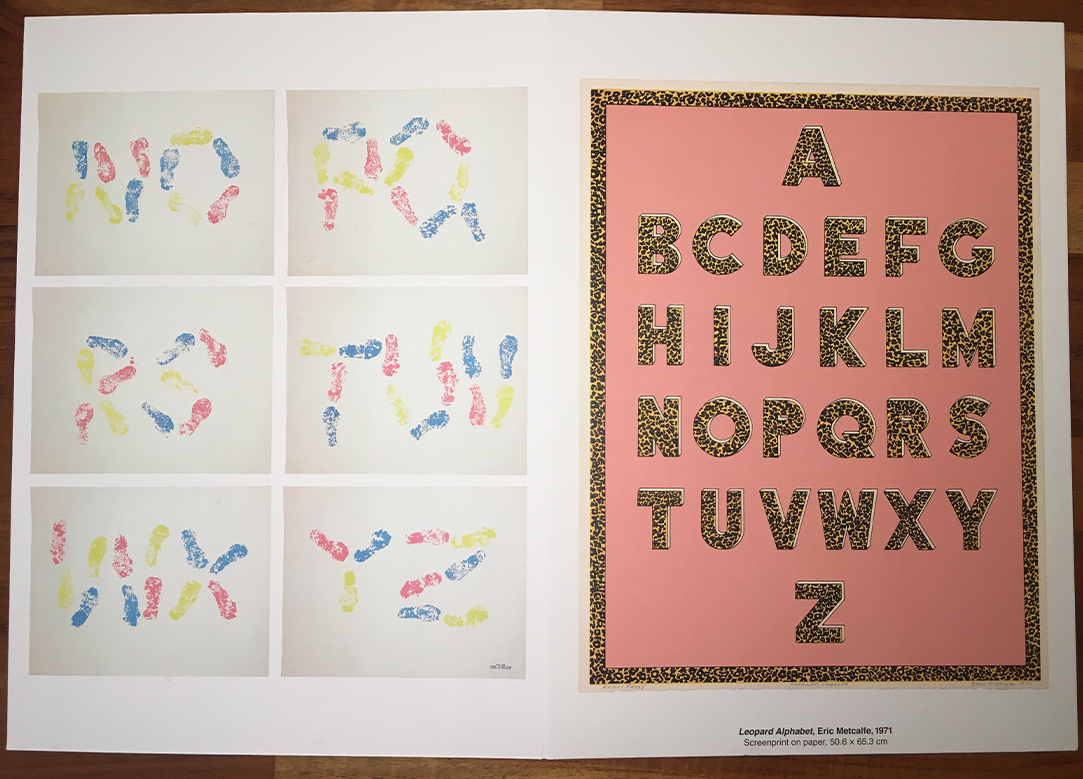

You look sick. Interesting but sick. You clearly don’t know how to match colours. Your choice of colours tells me you are a try-hard. I mean, who matches ‘vomit yellow’ with ‘lame blue’? You try to be the funny guy. Well, guess what? It’s not working. Your failed attempt is your greatest joke. Your reversed definition of the 80’s “Business in the front, party in the back” looks like a sad joke that wasn’t meant to be a joke.

Alright, so you want to be special, to stand out. And I want a good laugh so you’ve got my full attention.

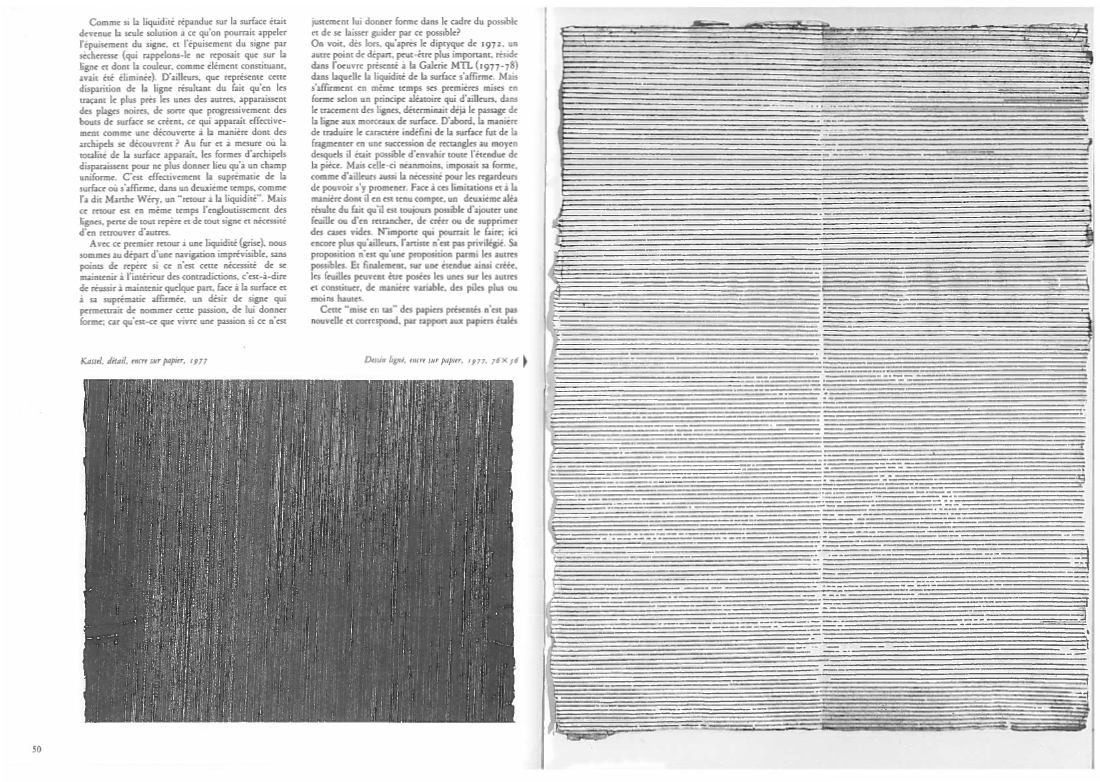

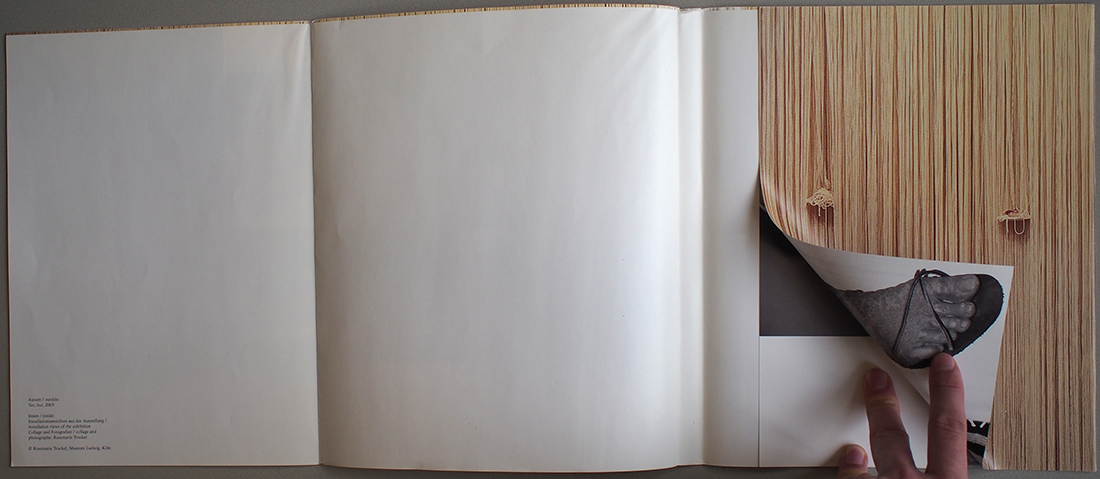

I let my fingers caress your face. My left hand supports your neck while my right hand explores the surface of your skin and all your edges. My index finger softly touches what seems to be your nose hoping to find some kind of depth. But you don’t have much depth, do you?

How disappointing.

You want to provoke me. And I am provoked. How weak of me.

I want to get to know you. Enlighten me. Please.

You start to open up, with my help of course. You grab my hand and tell me a story. A story I recognize inside of me. Your double-sided sense of humour is cute.

I can’t wait to get to know you better. You make me such a cliché.

To find out who you are, to get to know you better, I will have to do some research about your creator, your God, your inventor and designer.

And quickly I find out you are all one and the same person.

The man and the book. The book and the man.

I’ve already made the mistake of judging you by your cover and I won’t make the same mistake with your master.

Well, maybe you didn’t want to be judged exactly but your creator sure wanted to catch my attention.

So, who are you, great creator?

Both the designer and the artist, I see. Or maybe the artist and the designer.

You choose to have give written words but a title and a “thank you”.

As a performer and a photographer, you don’t need words. You tell stories with pictures. I get that.

But I must admit it makes me wonder. Many questions appear. So, I wrote you an e-mail. Know that I am looking forward for you to get back to me with some answers.

Still I feel like I know you quite well through my research.

Funny, isn’t it? I know you but you don’t know me.

You reveal so much of yourself and you almost eager for it. In that way, we are very alike.

We are quite connected to be honest.

First of all, through the academy;

“At the Rietveld academy, we are bit like a family”said the man who made a speech on my first day at school.

I agree with that, brother. You had your first day 40 years before me, maybe another man said something similar that day.

As I mentioned before you are a photographer. Guess which department I’m going into after Basic year…

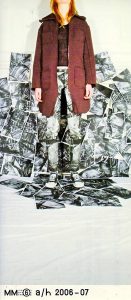

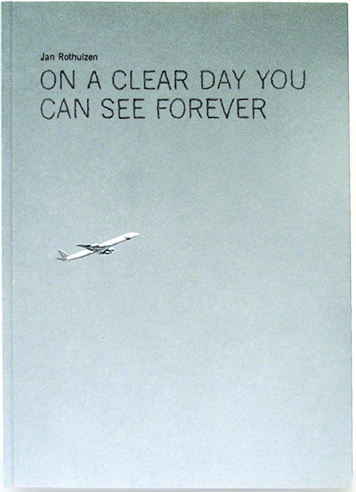

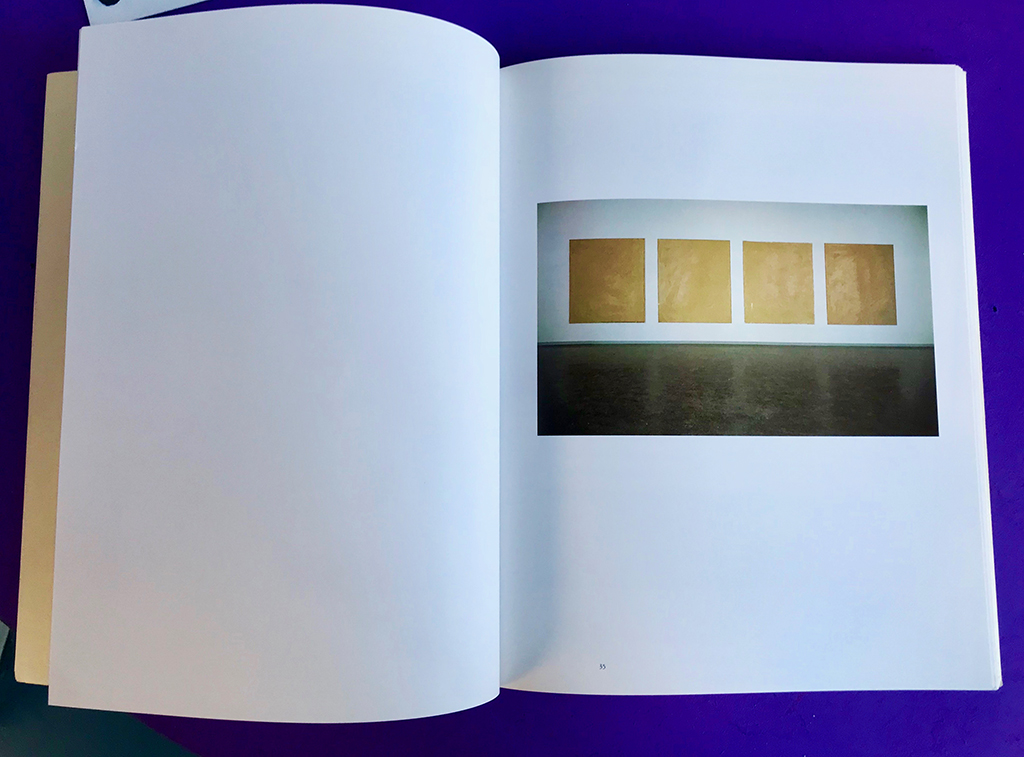

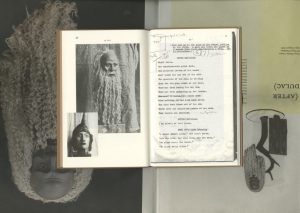

Inside of you I found this photograph.

A man laying in bed, naked. On top of him there is a mirror. His face is hidden and the mirror makes a distortion to his body.

Now let me describe you a photograph I made for the home assignment for the entrance exam.

My littlebrother laying in bed, wearing nothing but stockings. On top of him there is a mirror. His face is hidden and the mirror makes a distortion to his body.

Yes, I definitely understand you.

My teacher told me you are having an exhibition soon. I wanted to look up where this exhibition will take place. But I forgot. Not that I don’t care, I promise.

I just have many things on my mind, you seem like the kind of guy who understands.

But let me tell you what happened:

So, I went to get a piece of cake here the other day. A café near the academy.

As I walked to the café I came across a corner shop with some interesting art pieces laying around the floor and some masks hanging from the ceiling.

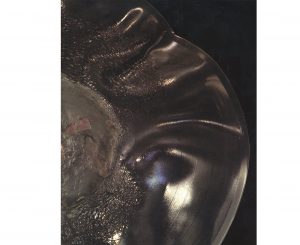

Your masks.

The masks you already showed me the first time I took that square piece of you down from the library shelf.

What are the chances? I could have gone to any cafes, any directions, away from you. But you wanted to show me the masks in real life, didn’t you?

Masks. Why masks? Who are you trying to hide from?

I would never use masks. In that way, we are very different. Or maybe not too different. You see, I put on a specific face when I take self-portraits. So, in a way that is a mask too.

Maybe you will give me an answer when we meet up in the near future, Ton.

When you find out that I exist.

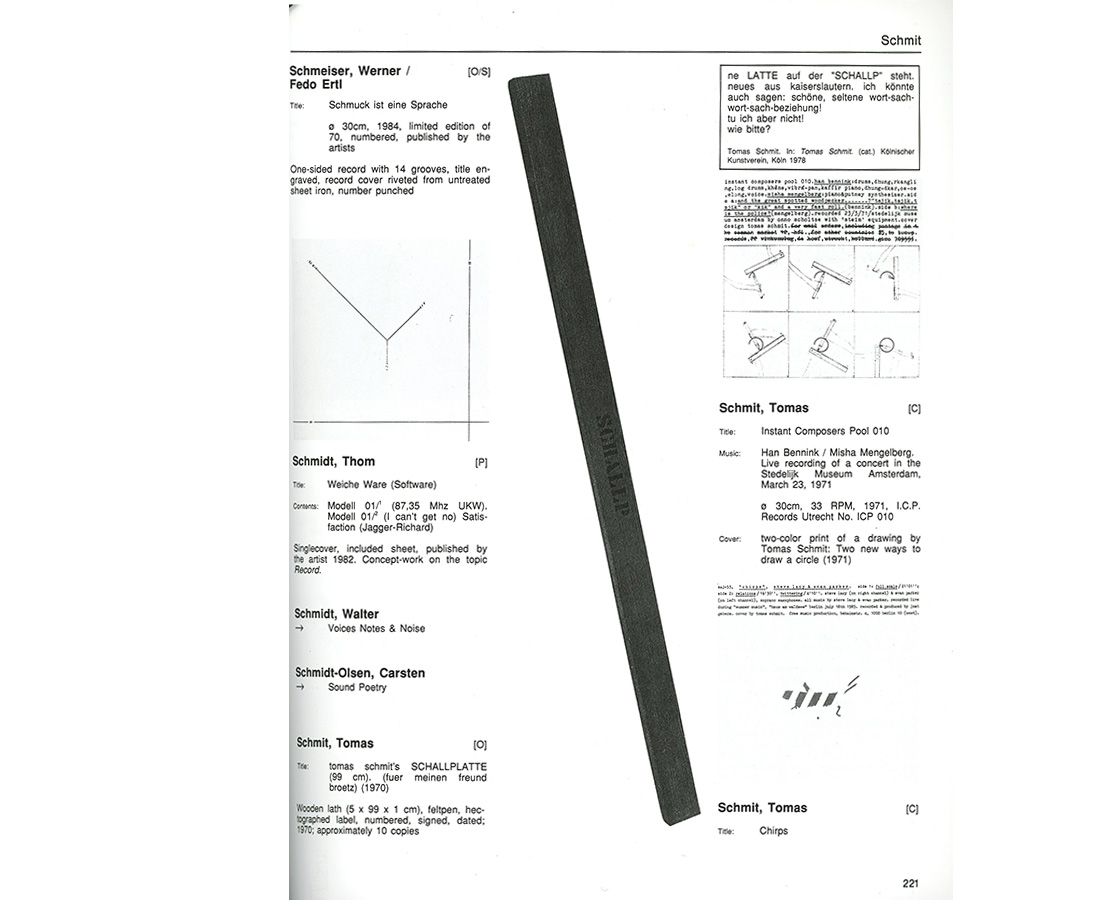

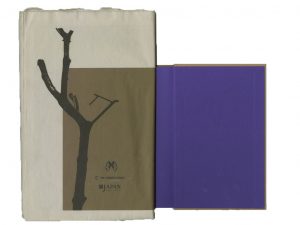

?: ?. design by Ton, Rietveld library number: 21620 1

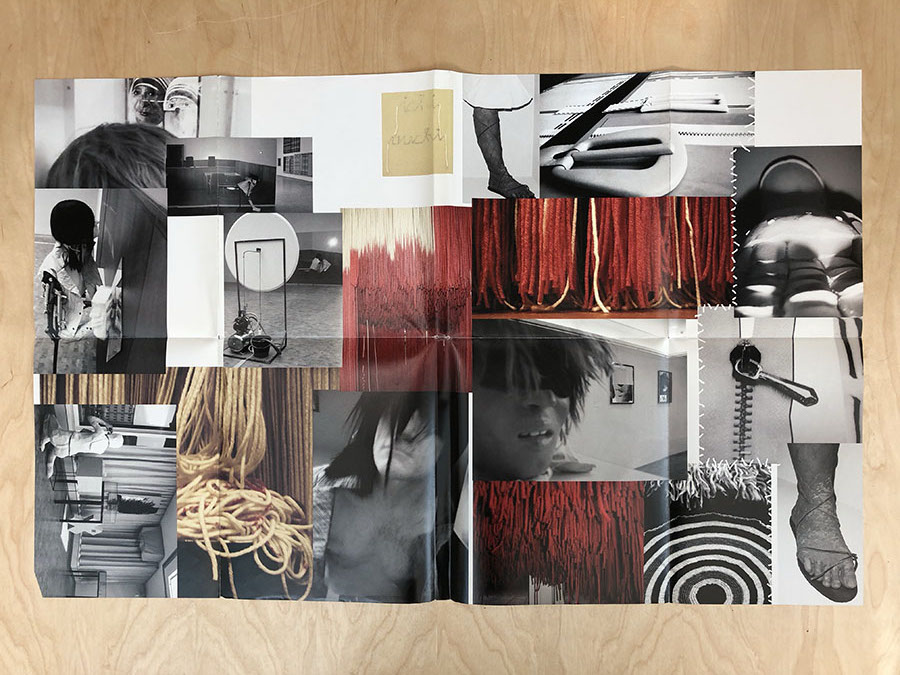

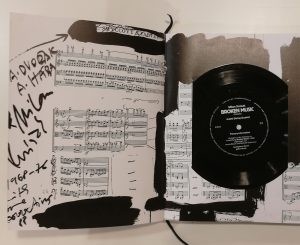

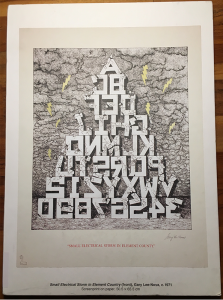

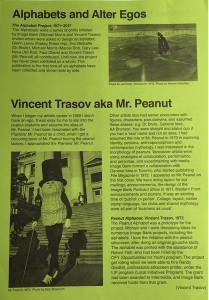

All capital font in white the same white the cracks and edges consisted of. I curiously flicked through, this tattered book comforted me like my grandparents, I felt accepted no matter how much knowledge I held. As I flicked through I saw a blur of red, blue then green. The same green as the cover. I then chose to start from the beginning and saw

All capital font in white the same white the cracks and edges consisted of. I curiously flicked through, this tattered book comforted me like my grandparents, I felt accepted no matter how much knowledge I held. As I flicked through I saw a blur of red, blue then green. The same green as the cover. I then chose to start from the beginning and saw