The 60s was a very significant era in terms of cultural and technological advancement. It was the era of counterculture, and a social revolution. It was the “space age”, in which there were countless advancements in technology and space exploration. It was an era of optimism and playful experimentation, in which there was a rise of avant-garde and outlandish sensibilities in art and design.

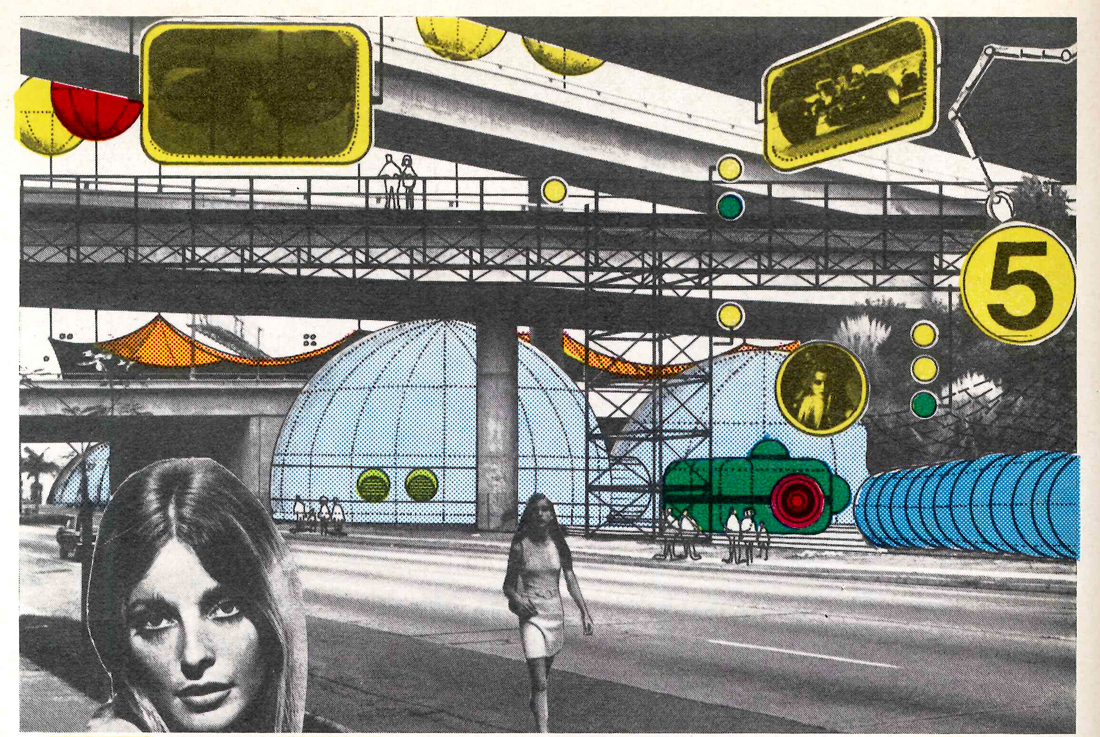

England was one of the main countries which experienced the counter culture of the 60s very intensively, so called the “swinging sixties”, and this reflected evidently in art, design and architecture. Archigram is an example of a highly visionary, avant-garde architectural movement from that time and place. They were very experimental and pro-consumerist, and were very significant in that they questioned and opposed to the traditional conventions of modernist architecture and city-planning, finding it to be too homogeneous and lacking of individuality. They defended individualism; that each person should be able to be part of the design process of their own homes, those homes should be personalized. They also defended expendability; that cities could change and grow constantly through time. They were highly influenced by trends of the era in their designs. Their aesthetic was very in line with pop-art, with lots of imagery of consumer products in their designs, which makes sense considering their pro-consumerist stance, and their perception of housing as a consumer product. They were very technologically forward and optimistic, and indubitably utopian.

The Plug-in City is an example of one of many of the outlandish designs proposed by the members of Archigram. Designed by Peter Cook in 1964 – the leading figure of Archigram; it proposed to have modular residential units which would be plugged in to a central infrastructure mega-machine. Adhering to the ideal of expendability, the modular units could be carried around by cranes depending on necessity and preference.

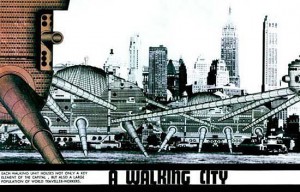

The Walking City is another project, proposed by Ron Herron in 1964, which proposed a nomadic city infrastructure in which none of the components of the city are tied to a specific location. Robotic structures would roam around, depending on where the owner wanted to take it.

Incontestably, none of their projects were actually realised. Their projects required technological advancement which would be far from where we are even in our current times. Even if one of their projects were attempted to be built, it would require funding. Indeed, their projects were quite utopian and optimistic, in true 60s fashion.

Utopian ideals in design seemed to be a common theme running through the era throughout the western world, another example being Constant Nieuwenhuys; a Dutch designer/artist who also proposed similarly utopian projects, which were also far from being realised. He also defended individualism, and was opposing to the traditional conventions of homogenous modernist city planning, but didn’t necessarily stand by pro-consumerism. He also made a proposition for a nomadic city, in which playfulness and creativity were inhibited.

There seems to be more of a cynical and pragmatic attitude in our current times, so these utopian ideals and optimism may seem superfluous to us 21st century folks (including me, when I first started reading about them, I was quite cynical about their outlandish projects) – but, perhaps such an optimistic and utopian attitude, and playfulness is exactly what we need, in our current world infected by political turmoil, and conservatism.

Project inspired by The Walking City

The Archigram archival project