Archive for March, 2011

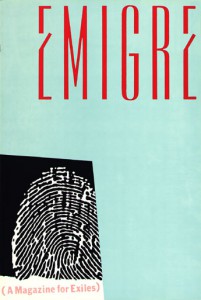

Emigre

Monday, March 14, 2011

Not so long time ago the Museum of Modern Art in New York has acquired

23 digital typefaces for their design and architecture collection.

Included are five Emigre font families:

Jonathan Barnbrook’s Mason Serif

P. Scott Makela’s Dead History

This acquisition marks the beginning of MoMA’s effort to built a collection of typefaces documenting designs covering the twentieth century. These fonts are synonymous with the early days of the digital era. In their designs they exhibit the experimental variety and technical challenges and opportunities brought to type design as a result of the introduction of the Macintosh computer. No type collection is complete without them.

In 1984 Rudy VanderLans and Zuzana Licko

launched a type company named Emigre, based in Northern California, making it the first contemporary type foundry to sell original fonts made on and created for the computer. In addition to designing and licensing over 300 typefaces by a wide range of designers, Emigre also published a magazine for 21 years that published criticism and essays on graphic design while providing a beautiful showcase for Emigre’s fonts.

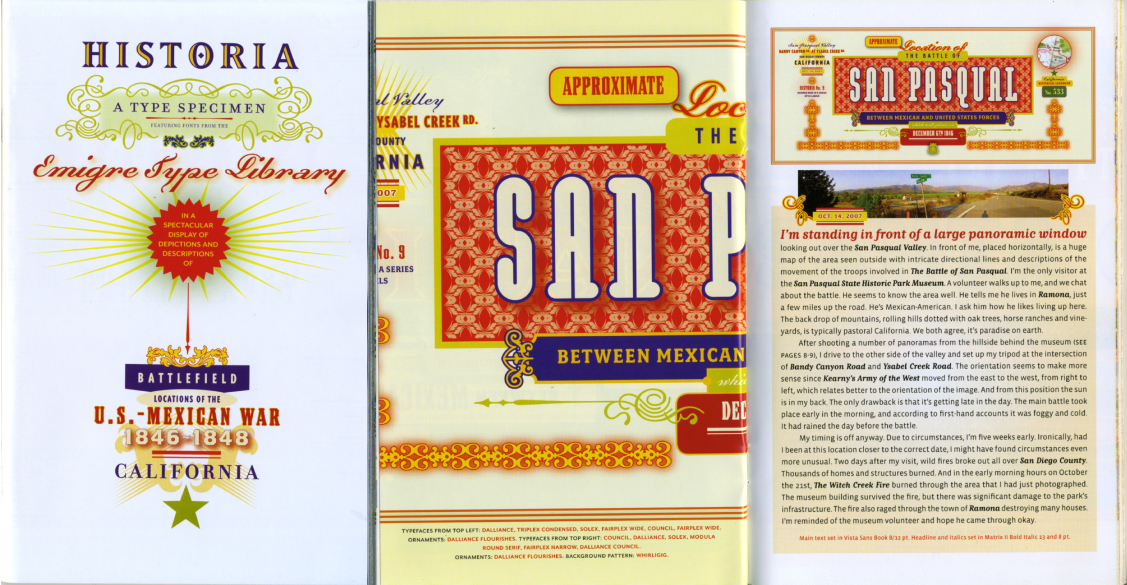

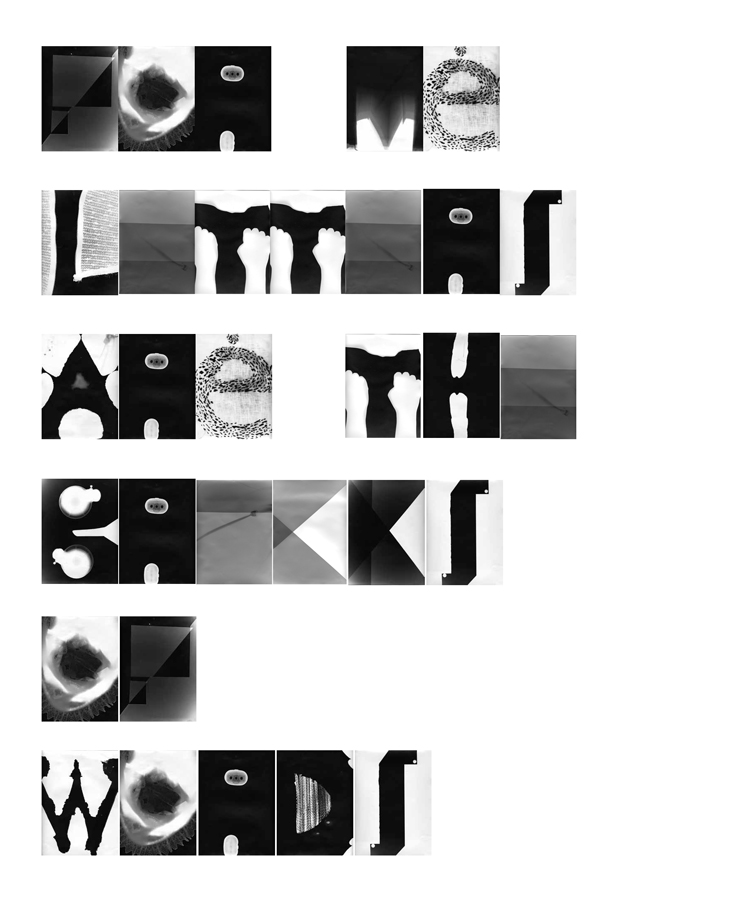

right: over of first Emigre magazine

Founded in these years, coinciding with the birth of the Macintosh, Emigre was one of the first independent type foundries to establish itself centered on personal computer technology. Must to say that Zuzana Licko was among the first to create typefaces made of pixels and composed of dots on a grid to be printed on early dot-matrix printers– From the beginning Zuzana Licko who is responsible for many of the beautiful and most popular typefaces in the Emigre library started to create fonts digitally because as left-handed she couldn’t be the best calligraphist and draw it by hand. She was using Fontographer- an application for designing fonts and exporting various font file formats As excellent designer Rudy VanderLans was also a good photographer– but the most I liked his Historia Type Specimen. He put different typefaces in one. It’s really amazing how he could do it without contradictions of fonts! Each “layer” is specific but together they creating good composition and looks very nice! He believed that any font can be successfully combined with any other font. It’s not so much a matter of which font combinations to pick, it’s a matter of how you use the fonts in combination. Size, color, tracking, contrast, layout and overall purpose determine how fonts can be combined successfully.

Emigre tried to be every time on the edge, they designed type faces, wrote articles, made their magazine like fresh air to designers and organize their exhibition as well! When one journalist asked them to look back what the did and their plans they answered they haven’t retired. They are still full of energy and looking into the future, and days are filled with new, exciting projects and creative challenges of all kinds. I think it’s the best way to be your own and never stop, only look forward and never regret about some failure. Emigre is not a company is just a group of people who are interesting in what they are doing! It the secret of any success!

Little Scratch

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

Gra-fi-ti [gruh-fee-tee]: markings, as initials, slogans, or drawings, written, spray-painted, or sketched on a sidewalk, wall of a building or public restroom.

This is the definition of graffiti in the dictionary. Everybody knows it. A tricky topic to work with I thought immediately. How was I going to tell you something new about this?

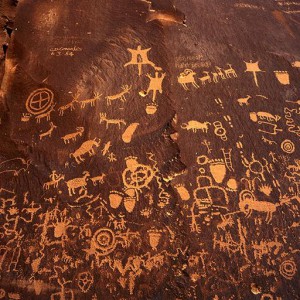

I started my research by defining what graffiti actually is. Soon I found out that the word graffiti means ‘little scratch’. I thought this was a detail of quite some importance as I assume most people think graffiti is mainly related to spray paint. But for thousands of years graffiti was made by scratching a layer away, revealing the layer beneath it. The first graffiti dates back 30.000 BC.

But also in ancient ‘scratched’ graffiti there is a big difference. For a long time graffiti was in the form of prehistoric cave paintings that were often placed in ceremonial and sacred locations inside of the caves. And we all know the Egyptian wall decorations and that only because of those we know the history of ancient Egypt. Unlike modern graffiti these inscriptions were not made to make a public statement but to visualize their religion or traditions for example. The First ‘modern style’ graffiti survives in the ancient Greek city of Ephesus (in modern-day Turkey). Local guides say it is an advertisement for prostitution. Located near a mosaic and stone walkway, the graffiti shows a hand print that vaguely resembles a heart, along with a footprint and a number. This is believed to indicate that a brothel was nearby, with the hand print symbolizing payment.

Still there was no political or social ideals displayed back in the times. graffiti consisted of Latin curses, magic spells, declarations of love, alphabets, political slogans and famous literary quotes, providing insight into ancient street life.

One inscription gives the address of a woman named Novellia Primigenia of Nuceria, a prostitute, apparently of great beauty, whose services were much in demand.

or a nice example of love ache:

Quisquis amat. veniat. Veneri volo frangere costas

fustibus et lumbos debilitare deae.

Si potest illa mihi tenerum pertundere pectus

quit ego non possim caput illae frangere fuste?

Whoever loves, go to hell. I want to break Venus’s ribs

with a club and deform her hips.

If she can break my tender heart

why can’t I hit her over the head?

-CIL IV, 1284.

When we think of the phenomenon graffiti nowadays, I assume people either think of individual expression (spraying names, political ideals etc on public spaces), or a form of art. Type in the word graffiti in Google and the masterpieces from Banksy immediately pop up. Although people never stopped making graffiti the way they did it in ancient times. we still carve our name and from the one we love in trees, doors and tables.

if we look at graffiti purely as a technique, this was originally scratching. taking a layer away to reveal another layer beneath it. this technique was in the first place used by potters who would glaze their wares and then scratch a design into it.

scratching is even more permanent than our modern graffiti is. spray paint can be removed although it’s quite a intense job, but something that is taken ‘scratched’ away is impossible to recover. A scratched work will stay there forever.

A modern artist using the scratch technique is the young Portuguese Alexandre Farto. He makes huge wall murals by scratching faces out of the surface. he doesn’t only use the surface as a material to work on, he integrates the whole wall, building and even surrounding into his work.

So finally, as a conclusion to this all we could say that the term graffiti actually doesn’t stand for our modern way of making graffiti. Or at least that it’s a different way of approaching it. It is a phenomenon that over the time lost a lot of it’s original characteristics.

A little heart scratched into a tree comes closer to graffiti than a mural from Banksy does..

LINETO

Monday, March 7, 2011

Since the start of our Design Theory/Research course about typedesign, graphic design, foundries, fonts , typefaces etc. we have had a look into a, for me unknown but, very interesting world.

, typefaces etc. we have had a look into a, for me unknown but, very interesting world.

This research will be about Lineto which is a foundry that these days sells there Lineto fonts, like replica, via their website and they have type-designers who publish their own fonts through Lineto. We will further explore the similarities between type design, graphic design and art.

My research question will start us out with some history to get a grip on all the different terms that are used to find out what Lineto actually does. For me starting out as a rookie I’m trying to grasp the meaning of this all. This is an interesting step that can also help you in understanding this world on its own. After that we will dive further into the question what the similarities are between type design, graphic design and art.

A type-foundry is a company that designs typefaces. Typefoundries used to sell their typefaces made out of wood or metal and matrices that were used for line-casting machines like Linotype and Monotype. This is such a time consuming and expensive process that when the computer started to be used it was replaced by digital type which is mostly used today.

Now to first get some terms straightened out. The term typeface is often mistaken or used for font. The two terms had more clear meanings before the start of desktop publishing but faded. What the difference between font and typeface is is that a font points out a specific member of a type family like roman or boldface, while typeface shows a consistent visual style which can be a family.

Back to Lineto, Lineto sprung up into existence in 1993 right at the time when the computer started to get used extensively in people’s daily lives. The foundries in this computer age where called digital type foundries which accumulate and distribute typefaces as digitized fonts created by type-designers.

Typefoundries always had used catalogues that were updated every year but since the digital type came in to the scene it was almost impossible for a foundry to make a catalogue looking at the amount of types that were created and distributed.

This way of working was embraced by Lineto and five years after starting their business Cornel Windlin and Stephan Müller the founders of Lineto jointly set up Lineto.com to distribute their own typefaces through the internet. They also invited a number of other designers to publish their fonts alongside theirs.

If you look at the fonts on Lineto.com you start to wonder what the difference is between type design, graphic design and art. There are differences between the three but there is also a very strong cohering similarity which you can’t deny and this I find an interesting discovery.

Starting out with describing graphic design you see that it is a creative process which involves a client who provides the work and then there is a producer, printer, programmer or signmaker of some sort. At the end of the process the result is used to bring across a specific message to the viewer.

In art you see that it is also very much a creative process which brings across a specific message but usually addressing different issues but the principle is most definitely the same.

For a type designer it is the art of designing typefaces. Where the typeface is one or more fonts designed with a certain unity. The function that their end product is used for is also about getting a message across to an audience, a better description of it is that it is a tool for bringing across a message to the viewer.

So everyone of the professions that are described above is about visualizing an idea concept or bringing across an idea or thought or a tool for doing so. Type is so rooted in our system and culture that we cannot escape from its grip, there are always fundamental links rooted at the core of it all. Looking at it in this way I think can open up your mind to look at type in a new and different way as an artist.

NORM formulating new dimensions in design

Monday, March 7, 2011

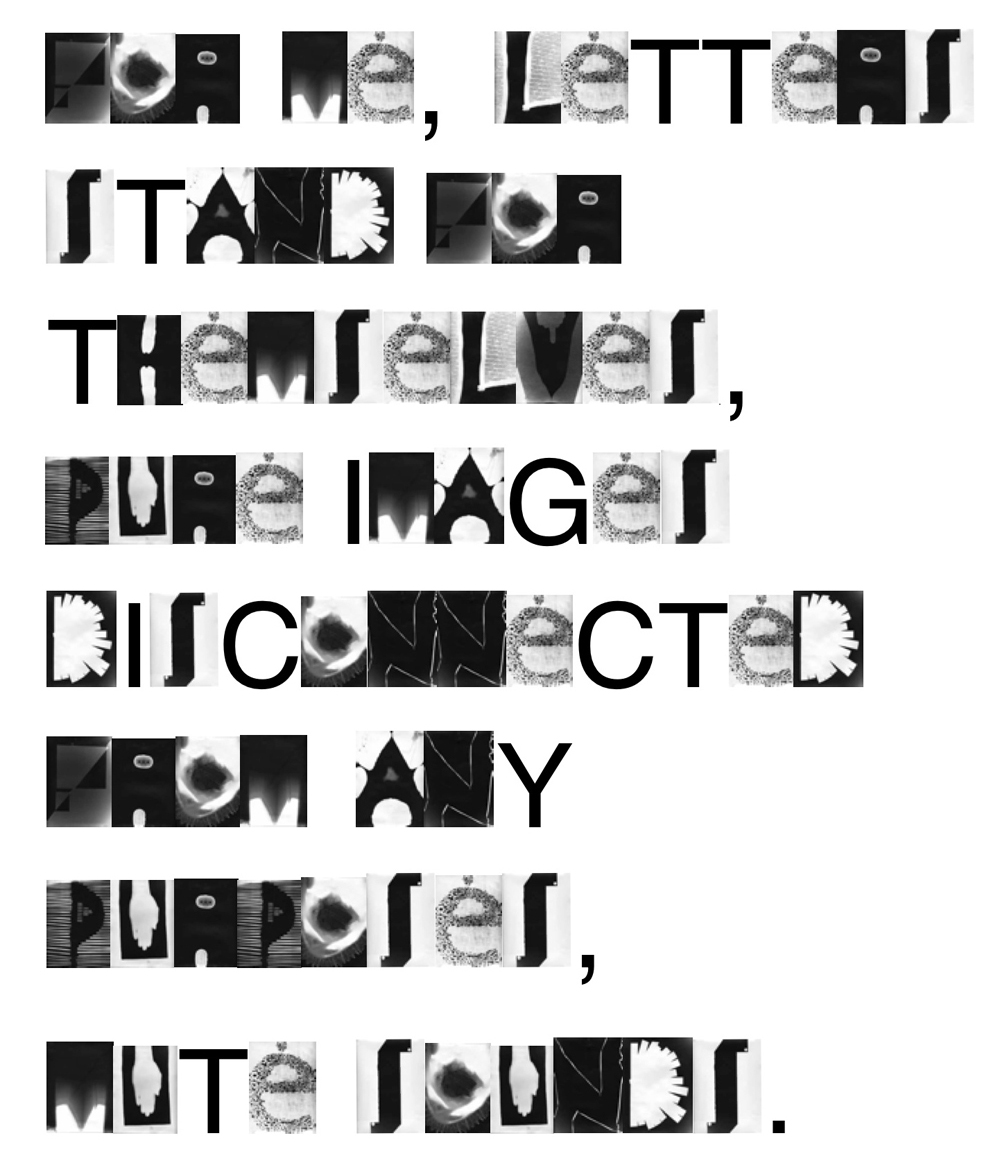

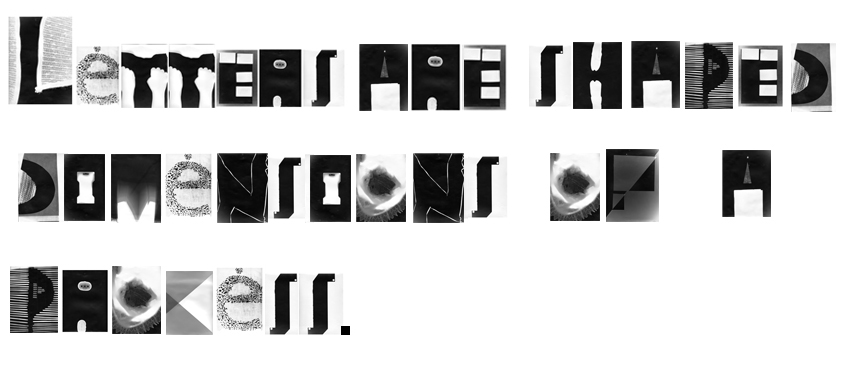

Dimity Bruni and Manuel Krebs,two graphic designers from Switzerland. Both born in 1970 and met in art school, in Biel. They founded NORM in 1999 and created their own typographic language by ignoring existing conventions. NORM is now based in Zurich. They’re well known for their typeface «Simple» which first got used in their book The Things. Later, Ruedi Baur of Integral, Paris, asked them to redesign the typeface for use in the new corporate design of the Cologne-Bonn Airport – this version is named Simple-Airport.

Bruni and Krebs developed their own typographical brand. They invented their own way of putting the world into categories and they formulated two rules: — the world is divided into two groups: 3d things and 2d things. — anything invisible is not of our concern.

3d things: 3d things consists of physical things that are of material existence. These items should be solid and visible, though not necessarily visible with the eye.

2d things: the 2d category can be put into four different groups based on dimensions. group 1, those which represent something pertaining to a three-dimensional space group 2, those which represent something not pertaining to a three-dimensional space group 3, those which represent nothing group 4, those which are as yet unknown to us

group 1 represents the physical spacial things. It is bound to its own being because we recognize 3d things through its build, size and materiality. When speaking in 2d matter, things lose their necessity of being a certain size, light, color. This is quite a wide range of objects, so NORM has categorized group 1 in sizes, — smaller than human beings, but large enough to be seen with the eye — roughly as large as human beings — bigger than human beings, but also small enough to be seen

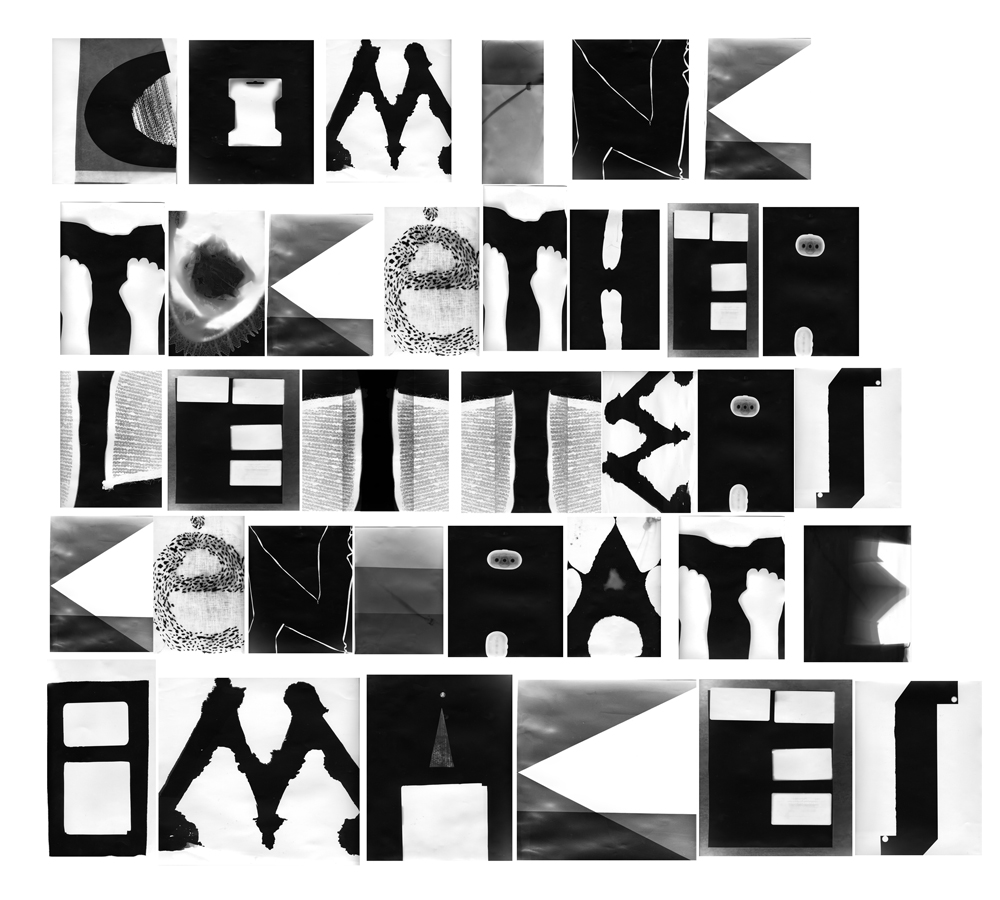

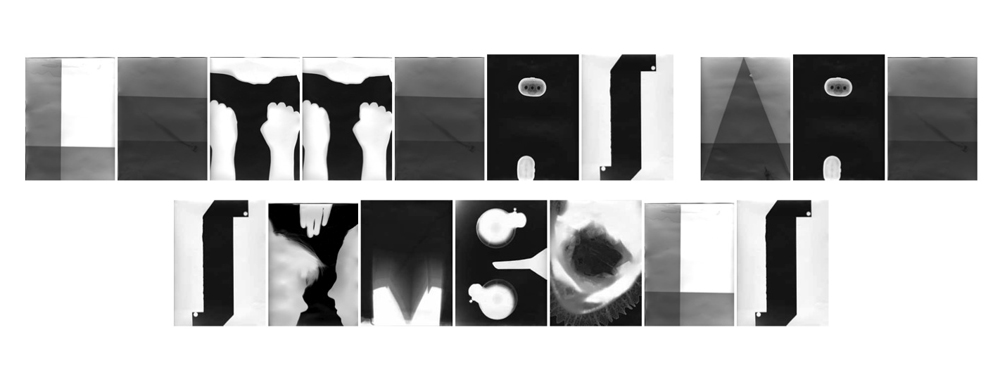

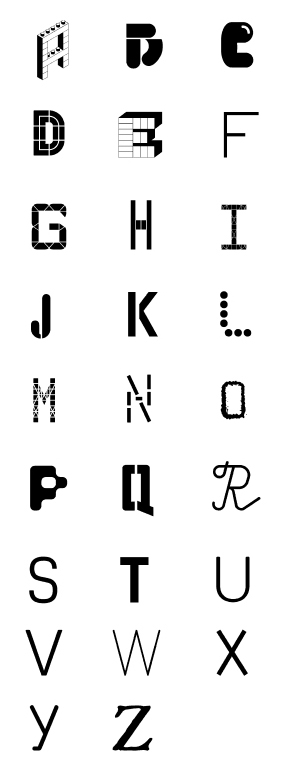

group 2 represents the non-spacious, nonphysical things. Things that come down to numbers and letters and abstract ideas like sounds. Letters are the most easy to understand. Letters can also be read as signs. They have a double function, we write them and read them. Letters define their own meaning in a very clear way; while sounds are more difficult to represent, read, and understand. Letters have principles, we have a certain way of making letters and this is why they are so recognizable. Letters are principles. Still, there is much room for playing and sculpting in this field. — when designing a new system of writing, signs should be simple. they should be simple, because it makes them easier to remember, to recognize, and reproduce. — also the signs should be in a small quantity, because it makes them easier to learn — no sign should resemble another, because it will create confusion. so each sign should appear no more than once — it should be possible to align the signs in straight rows. always on a horizontal/vertical grid. this is so we can recognize a text, even when the script is unknown to us. — the characters should be simple graphic forms, recognized, and written easily as possible.

group 3 These things represent nothing. the things indescribable and invisible, so no concern

sans Comic Sans

Monday, March 7, 2011

Annual design awards is an event which is announced almost by every design magazine/ company/ institution, whether it is the influential “Wallpaper” or just a blog of a random fashion lover. The best is picked out of everything, “from beds to breakfasts through jeans to genes”. However, when all the winners are praised, the time comes to remember those who weren’t lucky enough to fit on the pedestal. Being nominated as the worst is rather a dishonor for every designer or design company no matter if it’s a car or a pair of shoes.

Nevertheless, sometimes ‘bad’ is not enough to describe public opinion about a design piece. ‘The worst of the worst’ may sound dramatic, but this is a title used talking about… typography.

It is difficult to find a font or, frankly speaking, any piece of design which would be accepted more controversially than Comic Sans MS. Its naive, innocent and childlike appearance makes it so attractive for primary teachers and prayer groups of local churches. Yet it is also immature, juvenile and silly as if written by a 6-year-old, yelling ‘bad taste’ at everything where it pops out.

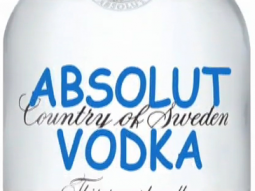

If some well-known logos were replaced with Comic Sans, it would look rather homely, warm, inoffensive and simply unsuitable. But when it comes to real examples, a restaurant menu presented in this font looks more like a kindergarden canteen while a warning sign loses its all respect immediately and seems to be rather an April Fool’s joke…

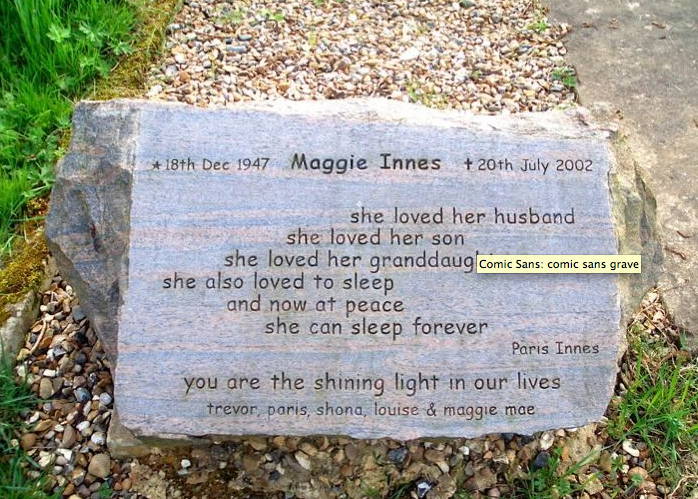

As if it was not enough, this font proves to be contagious. Ever since it’s first appearance in 1995, Comic Sans is now everywhere, even on the sides of ambulances or gravestones.

No wonder that such a vast misuse of a font has caused a big anti-Comic Sans campaign: various websites offers hilarious photostreams of Comic Sans spotted everywhere in the world; one can also email a comical educational pamphlet for a friend who is suspected to be a comic sans criminal. As if it was not enough, the hate campaign has it’s own website where special Ban Comic Sans T-shirts or coffee mugs can be purchased. Even more, visitors can donate for creating a documentary called Comic Sans Or The Most Hated Font In The World. The greatest haters can also download a special Safari extension which changes Comic Sans websites into Helvetica!

‘Every time you use Comic Sans, Faye will punch this adorable little bunny’, is written on a picture with a worried girl, holding a small white rabbit, crying ‘but I don’t want to punch the bunny’. The scale of hate sometimes seems to be taken to extreme or even absurd: “Misuse of the font is analogous to showing up for a black tie event in a clown costume”, claims the creators of the hate campaign.

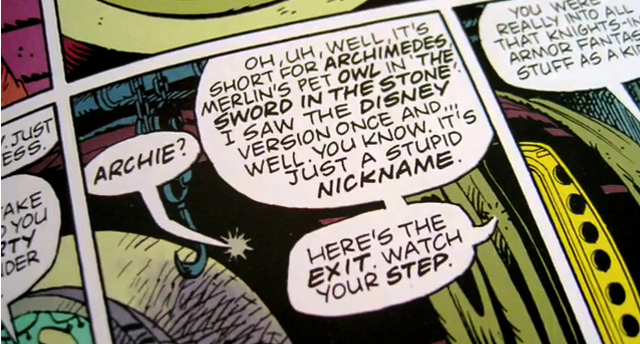

It is interesting to know that originally Comic Sans wasn’t designed for wide use. It was actually created for Microsoft Bob, a software program included in Windows 95. A little dog which was used as a help character ‘talked’ in Times New Roman, a font which was a bit boring, not warm and helpful-looking at all. That’s when Vincent Connare, a typographer who worked for Microsoft, was asked to create a special font for the program.

Apparently Connare was a big fan of comics. Inspired by “Watchmen”, a popular graphic novel, trying mimic its handwritten letters in speech bubbles, he ended up with now inglorious Comic Sans.

What was the secret of it’s enormous popularity? When Microsoft included the font in Word of Windows 95, Comic Sans suddenly bursted like a virus. It was something new, unseen and fun-looking. Connare explains it simply: “because it is sometimes better than Times New Roman”.

GRANDMASTER FLASH OF DUTCH DESIGN

Monday, March 7, 2011

This description appeared in my research on the Amsterdam residential graphic designer/teacher Karel Martens.

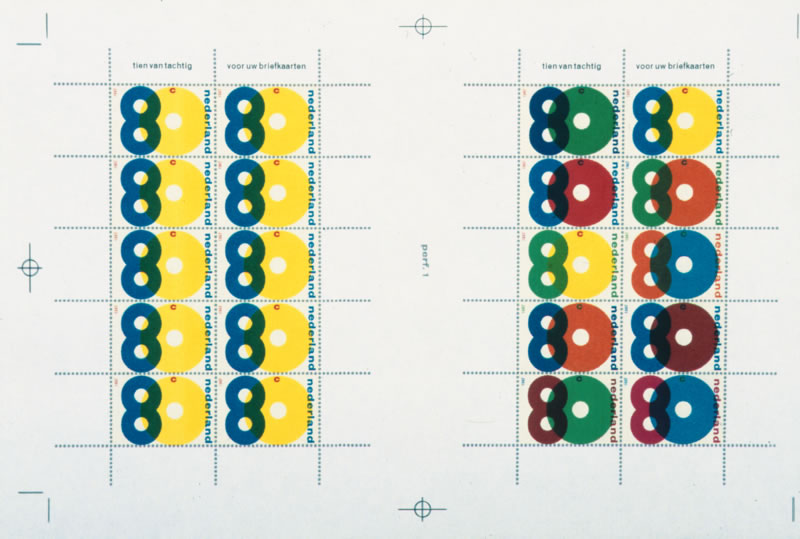

His name was stored in my memory, but I didn’t know anything about him, probably because I’m Danish and just moved here. I guess every Dutch person would or should know him or at least his works, in fact even touched them. He designed coins, stamps, phone cards and signs.

€ 5 (Queen) Beatrix and Vincent (van Gogh) coins

His style is very clean I would say; clear colours overlapping each other and forming a new colour. But what I really found interesting about his works is his way of translating a language or information into form or grid; his own new language.

proposal for a festive sheet of good-will stamps. The design was never executed

A good example of that is the façade he did of the philharmonic in Haarlem. It is situated in front of the big old church St. Bavo. I found some pictures on the Internet, but they didn’t give me the right impression, so I went to Haarlem to see it in real life.

The philharmonic building itself is very old, but as part of its recent restauration he designed this modern glass façade around the entrance and on a piece of wall high in the air.

l: the view of the glass facade from the church / r: glass facade entrance

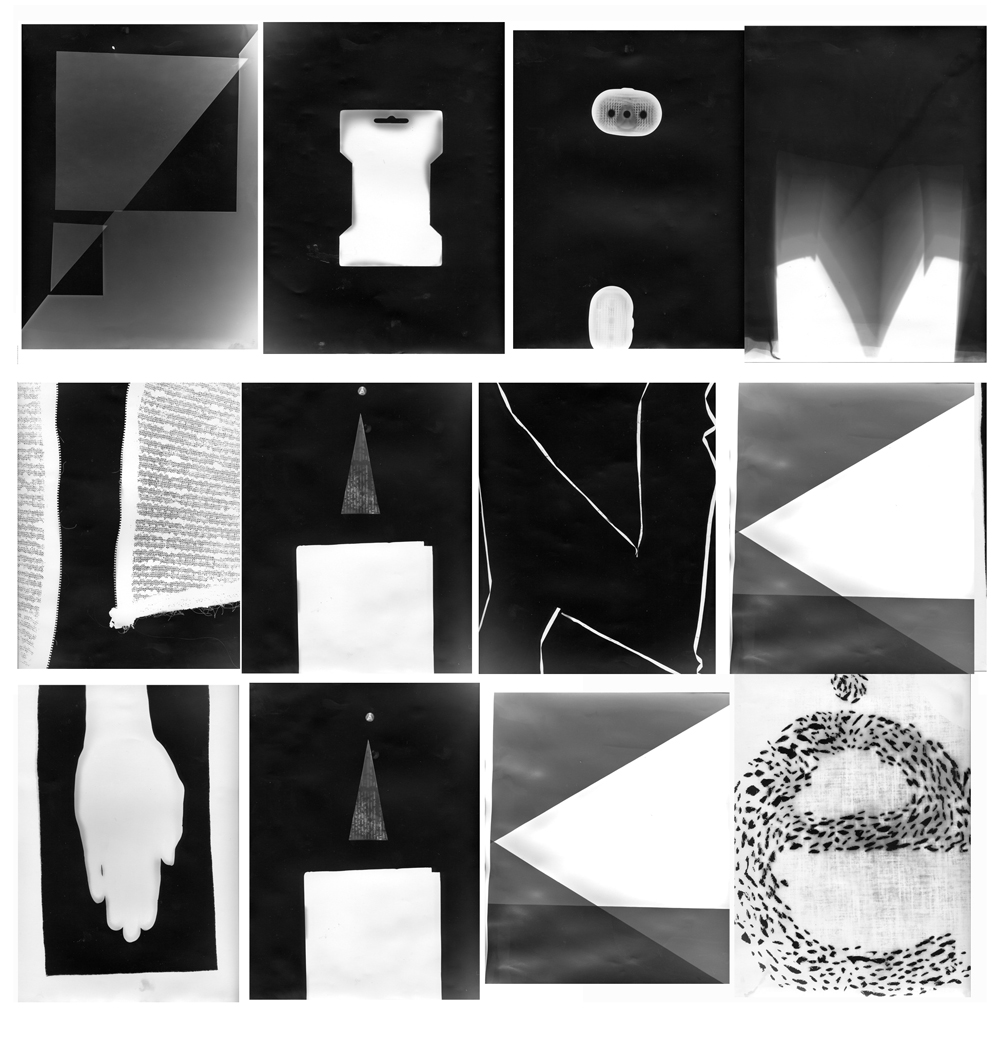

Karl Nawrot, fascination for the In-Between

Monday, March 7, 2011

Typefaces always seem to be facing the wind, two feet on the sheet of paper, unmovable. Like a silent army, arranged according to there ranking, there are ready to take a new formation. This traditional and almost absolute arrangement tends to make us forget how those typefaces got there, what is there personal journey, what and even who shaped them like that.

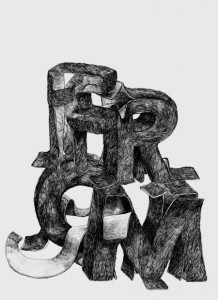

Karl Nawrot seems to be privileging this particular journey i am talking about. So to say, his typefaces carriers are far from being all traced beforehand. Moreover, he seems to be having even more fun in creating devices and means to form those letters than in the final presentation.

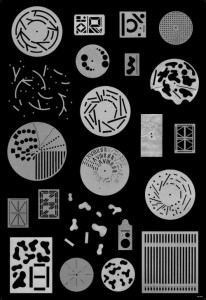

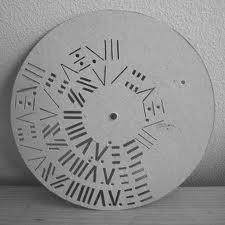

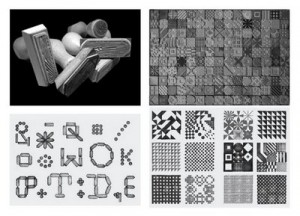

By using tools he creates himself, he lets the door ajar to imagination, not exhibiting the letter as a final assertion but as a possibility. Stamps, enigmatic stencil disks, collages celebrate as much the process as the result.

Thereby the designer does not hesitate to present those tools, such as the stencils disks, also through a series of posters, respecting somehow the presentation of typefaces. By creating a parallel in the presentation, he builds up a clear bridge between the making and the result, putting them on the same level of importance.

Through this interstice he offers us, one can let his imagination grow about what could be the final arrangement.

But is it not the definition of children games ?Making use of the possibility of the material and playing around it more than gathering all the forces to the final result. Indeed he does not only create his own tool, he also documents the process by making use of stop-motion movies.

Once again the use of this device to present his work makes it really fun. The videos or clip-arts that can be found on his website, www.voidwreck.com , are, according to me, by no means instructions for the proper use of those tools but once again a celebration of its inner-possibilities.

Thereby, in a interview he gave to the blog Manystuff.com in January 2011, he gives his definition of what a good design is. He declares : ’’A good design gives you the feeling of a piece stuck between past & future.’’

Playfulness is definitely the word I would use to describe the work of Karl Nawrot. However focusing on this aspect would maybe undermine the importance of geometry in his creations. Indeed if there is space for game and ‘’abruptness’’ in the realization, there is a clear rigor in the fabrication of the tool. On the one hand the Stamps Box conceived in 2005 and 2006 has a clear connection to childhood but on the other hand the rubber stamps consist of drawn geometrical patterns of the same size. Even if Nawrot limits himself to four simple geometrical shapes (rectangle, line, triangle and circle), he succeeds in generating 150 different stamps : the result of an intense research in exhausting the possibilities and combinations of shapes.

Still Karl Nawrot is not only experiencing with typography, he is also an illustrator but those two interests tend to meet again through the approach he uses.

Indeed the letters he draws seem to peel themselves off, falling into pieces. But the movement could also be interpreted in a reverse manner : the letter getting slowly their final shape under our eyes. Once again Karl Nawrot creates the ambiguity, describing physically this in-between he invokes below, ‘’between past and future’’.

Background :

Karl Nawrot attended the graphic design school Emil Cohl in Lyon, France. He was accepted at the Werkplaats Typographie in 2006. He is now established as a graphic designer and typographer in Amsterdam where he lives.

Turned to the grid

Monday, March 7, 2011

#####Turned to the grid#####

(Wim Crouwel)

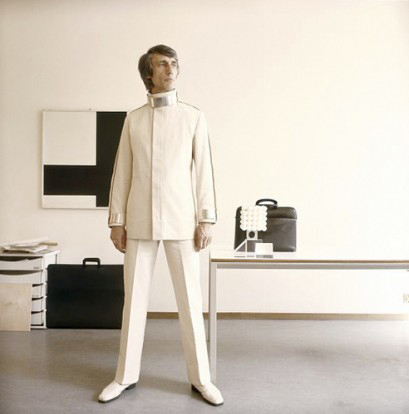

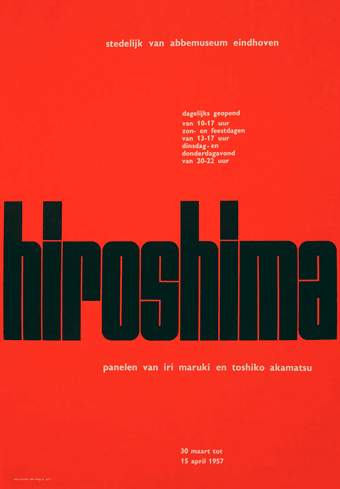

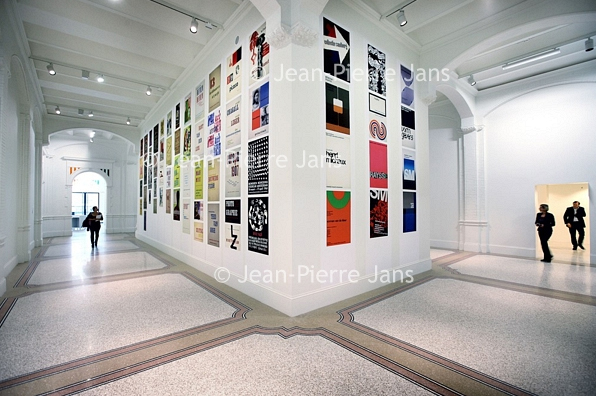

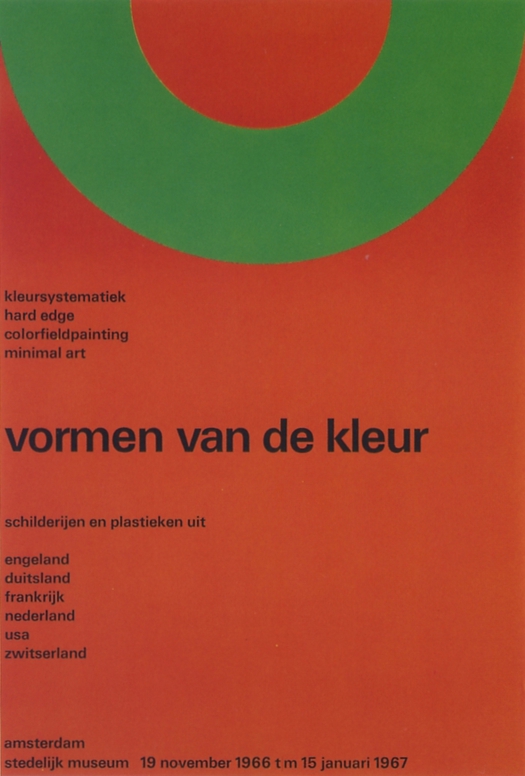

When walking through the main entrance of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam towards the coatroom one quickly notices the array of poster prints papered to the subwalls of the main stairs to the second level. These prints are from past exhibitions and many are made by the functionalist designer Wim Crouwel. When Willem Sandberg (director of the SM and did most graphic work) retired in 1962 Crouwel took the job and designed many from ’64 until 1984.

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Wim Crouwel Shapes of Colour exhibition

c Jean Pierre Jans Photography poster 1966, Contemporary Art museum poster 1971

Mondriaan or Miro 1958 (Letterpress), Vormgevers in SM, Hiroshima 1957

Wim Crouwel (Groningen, 1928) studied Visual Arts at the Academie Minerva in Groningen from 1946 until 1949. There he became acquainted with ‘The Ploeg’ artist collective that was established in 1918. His father was a block maker and perhaps this made the transition towards typeface design very logical. He Continued as an abstract painter with the ‘Creatie’ (Creation group) he joined the Amsterdam School of Art and Design evening courses and the Liga Nieuw Beelden (1954, co-created the Manifesto in 1955). The Liga was a group of urban designers making demonstrative exhibitions.

Geometrie/Menselijkheid

Sunday, March 6, 2011

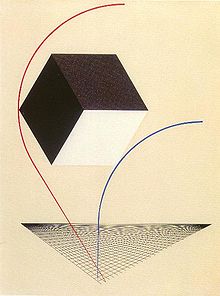

Als ik de El Lissitzky tentoonstelling in één woord moet omschrijven.

Geometrisch.

Zijn werkis architectonisch opgebouwd uit verschillende vormen, massa en kleuren.

Alles klopt.

Toch knaagt er iets.

Het begint bij de vergelijking van Malevich en Lissitzky. Waar je bij Malevich nog duidelijk de menselijke vorm kan herkennen, is het bij Lissitsky totaal geëvolueerd in iets anders. Vormen zijn meetkundig opgebouwd, tot iets nieuws, een mechanisch object.

Ik kom aan bij de driedimensionale uitwerking van Proun. Vormen, diagonalen en rechthoekige vlakken. In de kleine ruimte begin ik een zoektocht naar enige zachtheid of compassie. Maar helaas, die blijft uit.

In de volgende ruimte krijg ik een korte flashback naar mijn wiskundelessen op de middelbare school. Opdrachten waarin je moet bewijzen dat iets een vierkant is, de grote van hoeken moet bereken. Ellipsen, parabolen, ingeschreven cirkels, het komt allemaal weer terug. Hoe goed ik ook in wiskunde was, meetkunde bleef iets vaags. Misschien is het dan wel mede door deze herinnering dat alles voor mij vrij abstract blijft.

Natuurlijk begrijp ik hoe belangrijk en opwindend deze ontwikkeling in de beeldende kunst was, dat abstracte vormen gebruikt konden worden om iets uit te beelden, na eeuwen van portretten, landschappen en andere figuratieve werken. Ik denk dat ik ook niet zo zeer het figuratieve mis, maar iets organisch. Een organische vorm of structuur, iets grilligs en niet perfect uitgelijnd en afgemeten.

Maar dat doet niet onder aan mijn gevoel en ondanks dat ik weet dat het een geweldige ontwikkeling was, komt het niet binnen. De hele expositie lang heb ik moeite me te verliezen in het werk. Ik zie de kwaliteit, maar kan niet me er niet overheen zetten dat er een gevoel menselijkheid mist. De geometrie staat voor mij lijnrecht tegen over de mens. In zijn strakke, abstracte vormen kan ik mij niets voorstellen wat nog verder van ons af staat. Het voelt te opgebouwd en ondanks de dynamiek en de visuele taal die zo krachtig is, is relateren dan erg moeilijk.