BAUHAUS, NEW BAUHAUS, RIETVELD

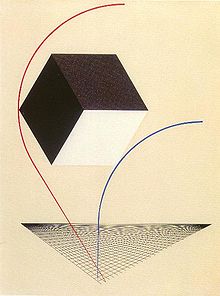

BAUHAUS WEIMAR, DESSAU:

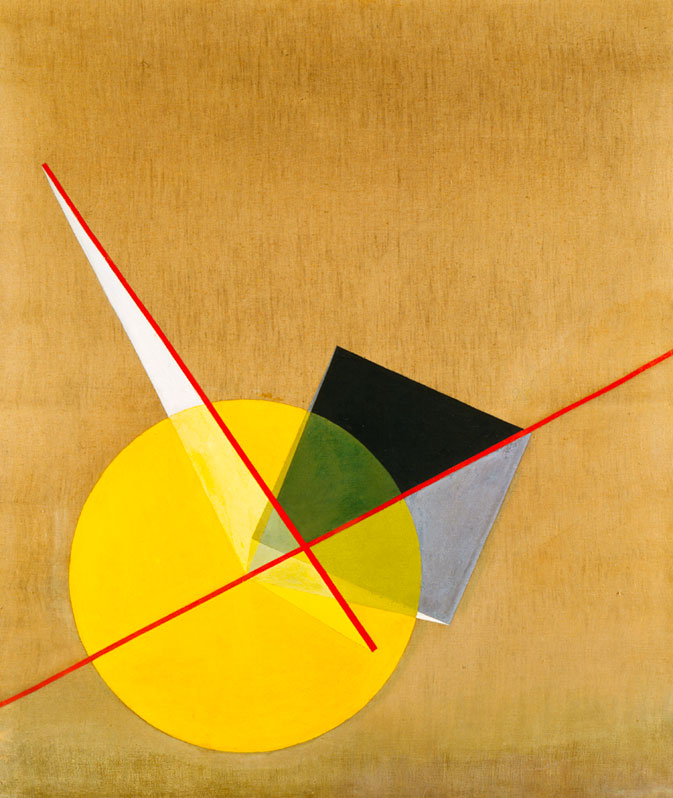

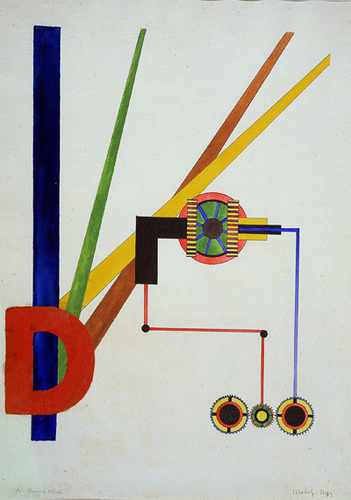

Bauhaus was established as a school for art and design in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. The school was originally located in Weimar, Germany but due to conflicts with the National Socialists it was moved to Dessau in 1926 and later to Berlin in 1932, where it was closed in 1933. The Bauhaus was the most influential modernist art school of the 20th century. Bauhaus’s approach to teaching, and understanding art’s relationship to society and technology, had a major impact both in Europe and the United States long after it was closed. The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon developments in all artistic medias such as architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography.

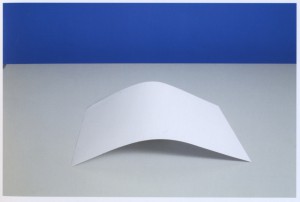

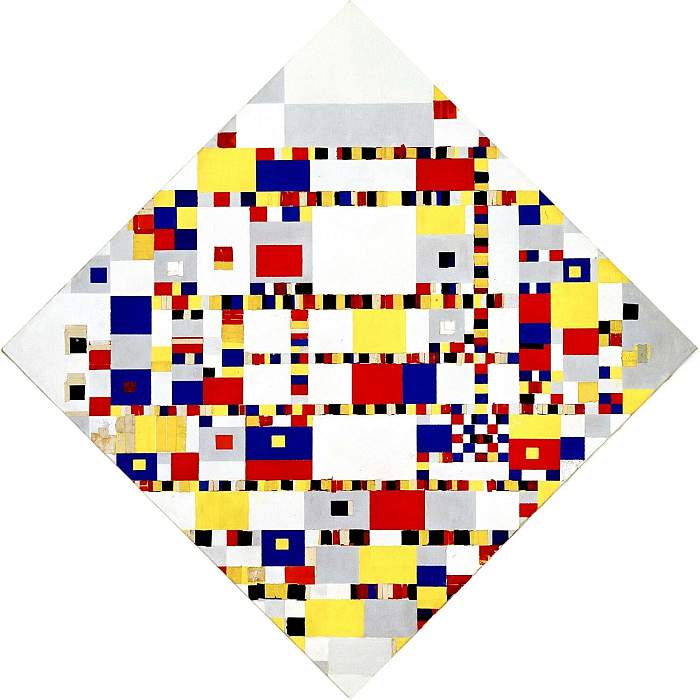

The goal of the artists of Bauhaus was to adjust to the industrial age by creating functional designs. Bauhaus attempted to integrate the artist and the craftsman, to bridge the gap between art and industry and to reunite creativity and manufacturing. Bauhaus emphasized on urbanity, technology and embraced the machine culture of the 20th century. According to Bauhaus the romantic hand making of products in the countryside should be replaced with industrial mass production. The industry demanded a reduction to essentials which meant a removal of former sentimental approaches and visual distractions. Bauhaus was originally a rebellion against the ornamentation and decoration that characterized the architecture, design and art before 1919. Things should now be more simple, functional and honest. With its clear, clean surfaces, rectangular and strict style Bauhaus fits perfectly with contemporary minimalism. Bauhaus was built upon the crafts tradition of England, (Ruskin, Morris) and Germany (Deutsche Werkbund) and concretized thereby a general reaction against the decadent style confusion and upper class ornamentation that characterized the period around the turn of the century.

Walter Gropius wanted a school with a renewed respect for crafts and technique in all artistic media, with an attitude to art and craft once characteristic in the medieval age, before art and manufacturing had drifted far apart. In the school’s early years it was suffering from a romantic medievalism where it pictured itself as a medieval crafts guild without any of the class-distinctions that formerly had raised an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist. In the mid 1920s Bauhaus School was moved to Dessau and Walter Gropius was replaced by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1930. The Bauhaus was based on the principles of the 19th-century English designer William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement that art should meet the needs of society and that no distinction should be made between fine arts and practical crafts (applied arts). It depended on the more forward-looking principles that modern art and architecture must be responsive to the needs and influences of the modern industrial world. Bauhaus was more like a workshop than a teaching institution. It was a “place to built” (Bauhaus) where masters and students after a two-year introductory course worked together in the workshops, where everything from teacups to buildings was crafted using the same principles and by time some of the same idiom.

In the late 1920s, when the Bauhaus in Dessau came under the leadership of the Swiss communist Hannes Meyer the whole school community was informed in a stronger professional and more scientific way. The school’s radicalism and its products were put into a tougher, social context and given a sharper political profile. This provoked the bourgeoisie formalistic and intuitive approach to art and corroded on the political tolerance. As long as the school could be excused as an anarchist hangout for inventive bohemians, it had the right to exist, but as soon as social critic was expressed, the Gestapo would interfere. Despite the fact that Meyer was dismissed in 1930, the school was put into administration and run by the politically far more acceptable Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

The school is also well known for its faculty, which included artists Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer and Johannes Itten, architects Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and designer Marcel Breuer.

The motivation behind the creation of Bauhaus came from 19th century’s anxiety about the soulessness of manufacturing and fears about art’s loss of purpose in society. Creativity and manufacturing were drifting apart, and the Bauhaus aimed to unite them once again, rejuvenating design for everyday life. Although the Bauhaus abandoned the sentimentality of the old academic tradition of fine art education, it maintained a stress on intellectual and theoretical pursuits, and linked these to an emphasis on practical skills, crafts and techniques that was more reminiscent of the medieval guild system. Fine art and craftsmanship were put together with the goal of problem-solving for a modern, industrial society. By doing this the Bauhaus school leveled the former hierachy of the arts by now placing crafts on a par with fine arts. With the emphasis on experiment and problem solving the Bauhaus has been enourmously influential for the approaches of arts education in the time after Bauhaus.

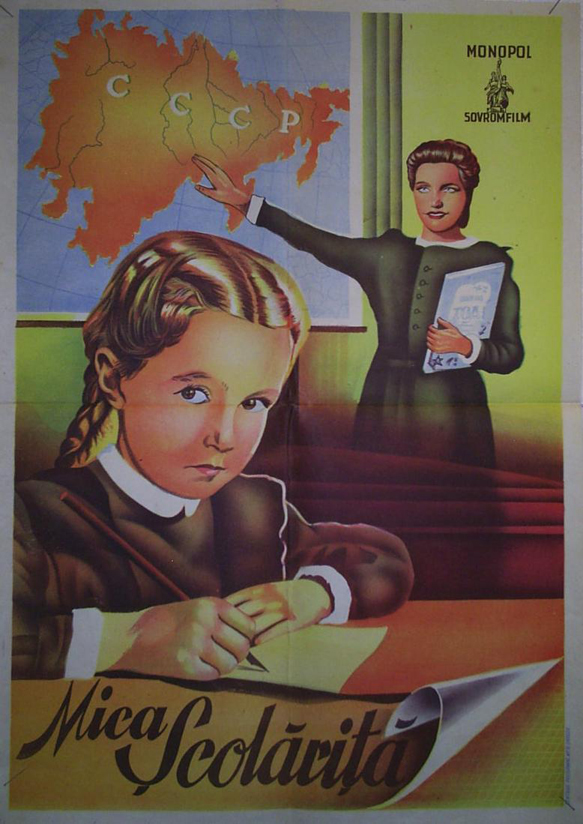

NEW BAUHAUS CHICAGO:

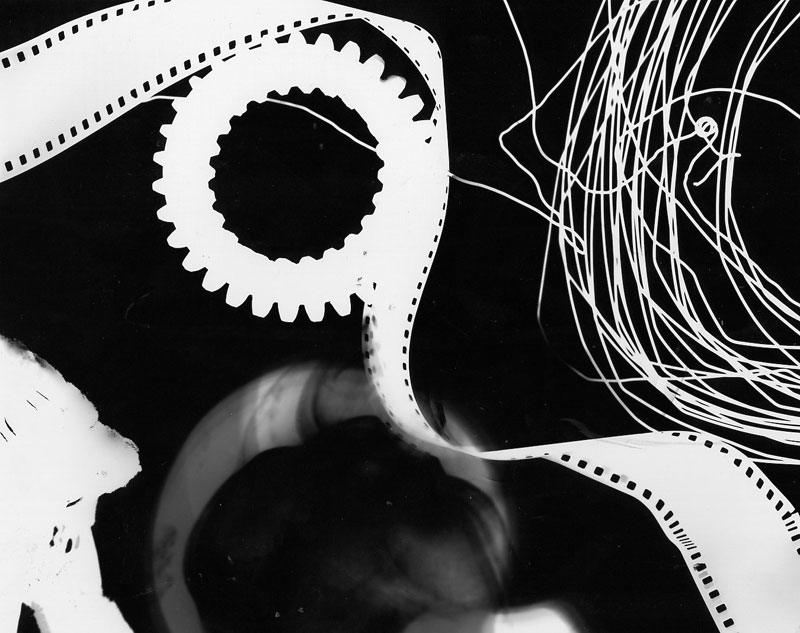

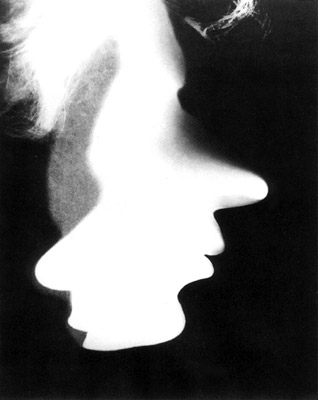

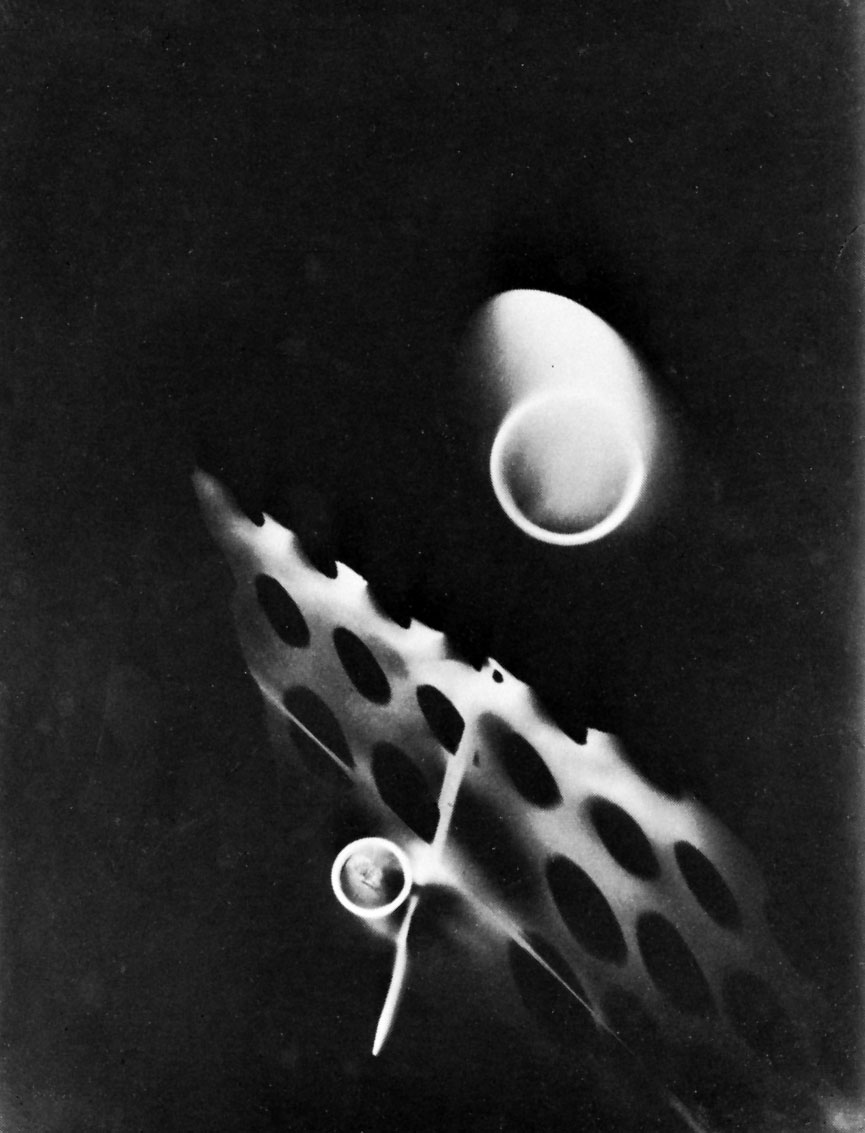

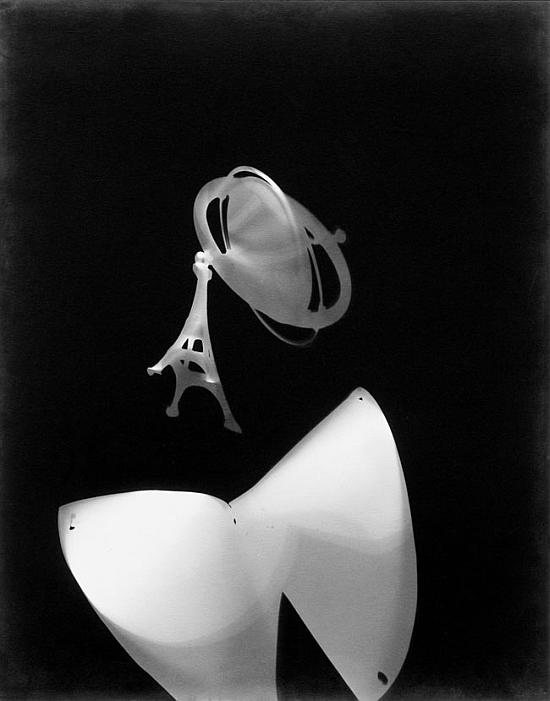

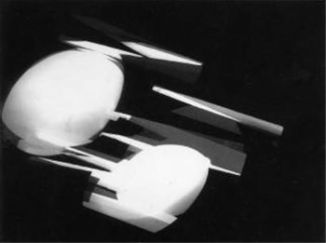

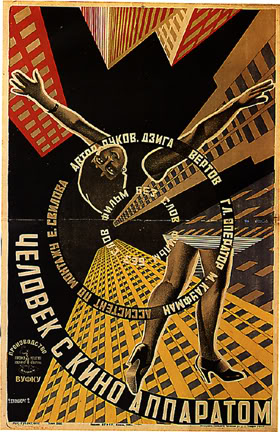

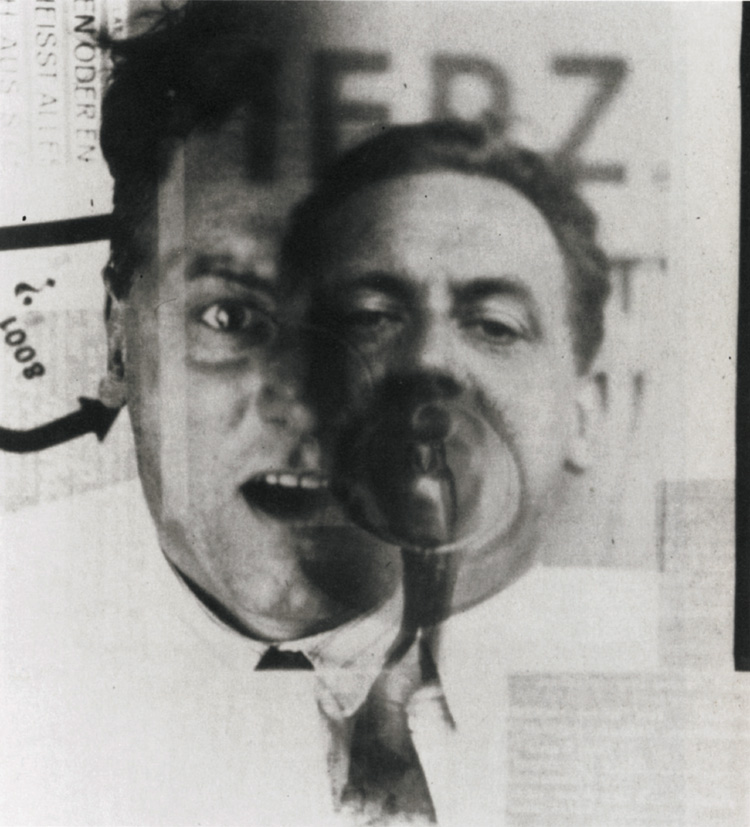

As many Bauhaus faculty members immigrated to the United States because of the German national socialist they contributed significantly to the development of North American art, design and architecture. Their ideas were especially well received in Chicago. In 1937 the New Bauhaus design school was founded in Chicago by László Moholy-Nagy who was a former Bauhaus teacher in Germany (1923–1928). Moholy was one of the early masters of The Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau, but he had to leave in 1933 due to the nazis. The Bauhaus philosophy lived on in the professional work of a few core members who emigrated here among Moholy. Though they left behind their homelands and native cultures they did not leave their convictions and allegiance to Bauhaus principles. The first to take the initiative of continuing the legacy of the original Bauhaus is a group of Chicago business people representing the Association of Arts and Industries. In 1922 the Association of Arts and Industries was established in Chicago to advance the application of good design in industry in order to better compete with European products. The Association hoped to establish a school to train artists and designers to work in industry and some of the members of the Association turned to the Bauhaus as a model of what their school should be. In 1937 the Association had invited Walter Gropius to direct a new design school in Chicago. Since Walter Gropius just had accepted a position with Harvard University, he recommended one of his closest Bauhaus collaborators, László Moholy-Nagy instead. In October 1937 Moholy became director of the school called “The New Bauhaus: American School of Design”. Due to financial problems and other factors the Association of Arts and Industries withdrew their support of the New Bauhaus which had the effect that it did not reopen in the fall of 1938. In February 1939 László Moholy-Nagy opened his own school The School of Design in Chicago. With no support from the Associatioan Moholy was still able to garner the support of faculty and key associates to continue the school Pogram under the name New Bauhaus – ‘School of Design’. Many of the faculty and students of the New Bauhaus joined the ‘School of Design’ and the school also had the support of former Association of Arts and Industries members, especially Walter P. Paepcke. The School offered day and evening classes, and Saturday morning classes for children. In 1944 the New Bauhaus ‘School of Design’ became the ‘Institute of Design’ which meant a reorganization brought about accreditation of the school and a renewed organizational structure which freed Moholy of the many administrative tasks of running a school. To show the change the old name ‘School of Design’, was replaced by ‘Institute of Design’, and the official typeface was returned to a slightly different version of the font used during The New Bauhaus Era. The school’s academic program consisted of a four-year course requiring all students to take several “foundation” classes depending on their prior education, training, or experience, before selecting an area in which to specialize. Visual Fundamentals, Basic Workshop and Basic Design were among the first challenges encountered by students. Other classes included graphics, shelter design, typography, sculpture, and textile design. Moholy stayed as director of the school until his death in 1946. He was replaced by Serge Chermayeff . In 1949 the ‘Institute of Design’ became a part of Illinois Institute of Technology during the administration of Henry Heald. The IIT Institute of Design as it is called today carries the legacy from The New Bauhaus and offers two professional degrees, the Master of Design (MDes) and the Master of Design Methods (MDM), and a dual MDes / MBA degree program with the IIT Stuart School of Business.

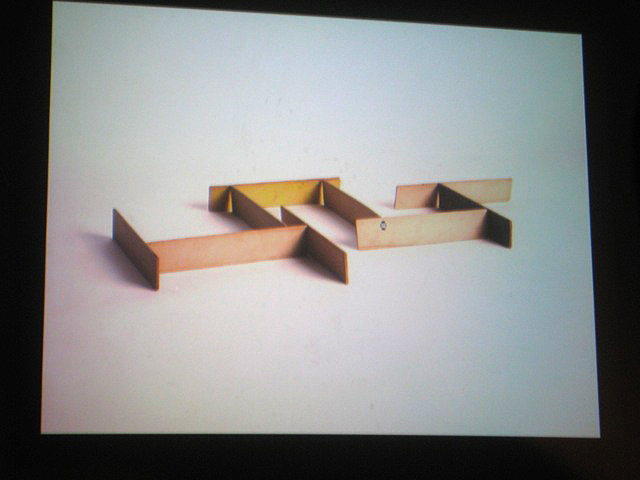

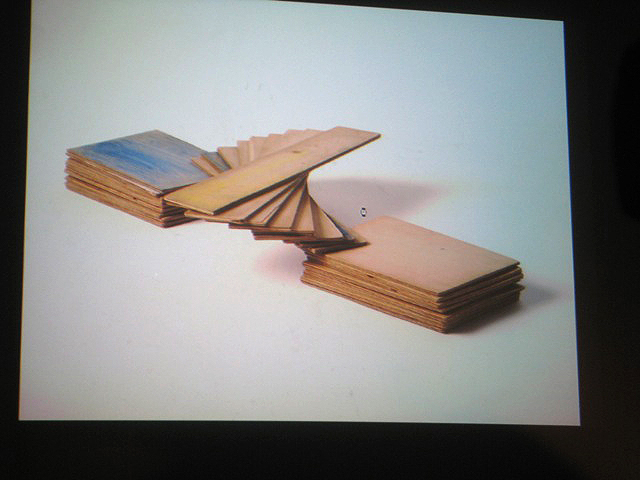

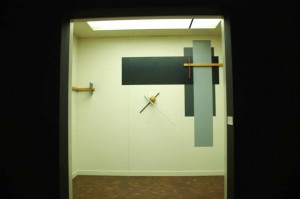

GERRIT RIETVELD ACADEMIE:

The Gerrit RIetveld Academie is a dutch art and design academy based in Amsterdam. The Academy is named in memory of the dutch Architecht and furniture designer gerrit Rietveld. The academy was founded in 1924 after a fusion of three older art academies and acts today as an independent school for higher vocational education. Rietveld has more than nine hundred fifty students of which about 40% come from outside the netherlands. From 1939 to 1960 the institution was under influence of the functionalism and political views of De Stijl and Bauhaus. This was due to the director Mart Stam who was an architecht with scoialistic political views. In the 1960s Gerrit Rietveld and his Colleagues Joan van Dillen and Johan van Trich Designed a new building for the institute. When Gerrit Rietveld died some years before the the project was carried out and the building was finished the institute decided to honour its builder in 1968 by renaming the academy from Kunstnijverheidsschool to Gerrit Rietveld Academie.

READ MORE IMAGE