Dying is something we all have to face one day.

When it finally happens, we trust on the people closest to us to give our remains a place to rest, playing the right music at our funerals and keeping us from being forgotten, by remembering us, and telling stories about us to our grand kids.

But what if a person dies who doesn’t have any close ones to remember them…

Who doesn’t have friends or family to attend their funeral..

In Amsterdam it happens multiple times a year.

The Pool of Death

Drug addicts, drunks or abusers rejected by friends and family…

Illegal migrants, wanderers and hobo’s without papers, permits and names…

Rejects and the misunderstood, whose mental disorder kept them living in seclusion… Recluses who cut off all social contacts or lost everyone that was ever dear to them… Elderly who outlived every last relative… Youth, abandoned and unable to survive on their own…

The pool of death is a group of poets, who honour the lonely deceased.

As the sole attendant of a lonely funeral they accompany the lifeless remains to the grave where they recite a specially written poem.

To write about someone, and give their story to the world, a poet needs to learn as much as they can. Like a detective, they look for clues. They visit the homes of those lost, talk to their neighbours, and search through city archives gathering as much information as they can to form a sense of the person that was.

The same week i received the assignment (to meet up with someone that inspired me), I attended a funeral, my second of the past two years. This very present sense of death and mortality made me think of the Pool of Death and the Foundation of Lonely Funerals, a project by artist/poet F. Starik.

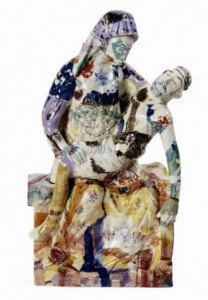

Images above by Jan van Breda

Frank Starik

I had met Starik once before, about a year ago, when he was clearing out his workspace. He was leaving his current atelier to work from home, and couldn’t bring all the things that had come to fill that space. I got a tip from someone very close to me who was helping him sort out what he would take with him from what he would sell, that the rest would be thrown out.

Amongst all the things, I found this big box. Inside it, were all these wooden crosses. They were old crucifixes that all seemed to be missing their christ figures, leaving them to look like movie props for an old Hammer production starring Christopher Lee. When I asked him why he had so many of them, and what happened to their prophets, he addressed me in the solemn but raspy voice of a chain-smoking reverend:

“Well my son, I have dedicated a great part of my life to freeing Jesus from the cross…he’d been hanging there long enough!”

When I later continued my look around, I found an army of Jesus dolls lying carefully displayed on the ground, as if they were all out sunbathing on the beach.

Along with the crosses, I left with some old photo works. Most of them were collages made on old canvas frames, all black and white.

The Detective

On an early Sunday afternoon I went to my appointment with Starik at his house.

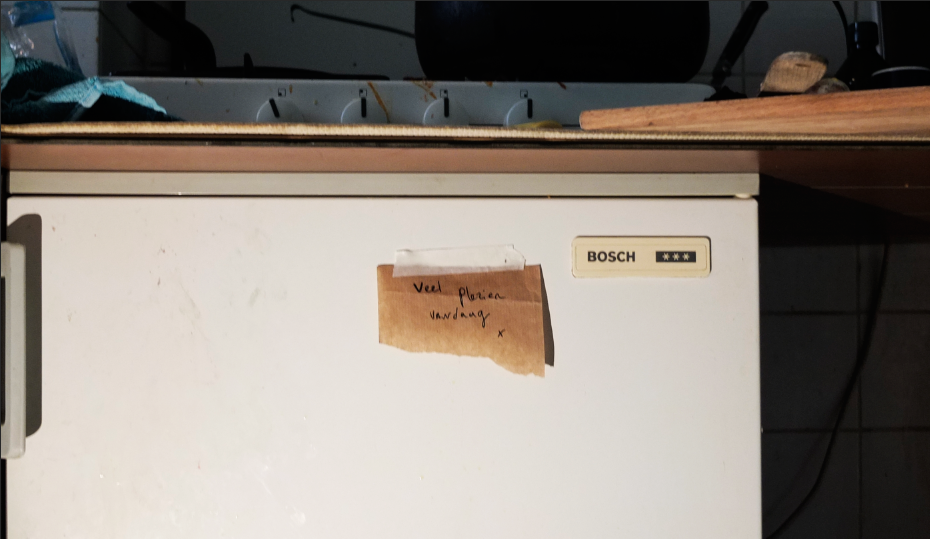

Next to his writing table stood an enormous plant and above his couch hung a note saying: “we are decent and normal”. Some of his work’s consist of a note or message, handwritten on a painter’s canvas. I really like these works. They might seem simple but they work really well.

I was curious about the proces of writing a poem for a person that just died, in total solitude. Somebody you’ve never met: how do you learn about them? Are you allowed to visit their homes and search for clues like a detective?

He told me that sometimes it was very difficult, depending on the situation. He was allowed to go into their homes, but a lot of times these were in total chaos. The anonymous deaths are often discovered when the neighbours call the police to complain about the smell. It can be weeks before they are found, and by then, the bodies are in a state of decay. But sometimes you can find something that can be of use. He confirmed my suspicion and said it was very much like being a homicide detective. He always makes a talk with the neighbours, and if the person still has some long lost family members, searching the city archives can be a big help.

Sometimes people have a strange relationship with public workers, relationships that in a way replace the lack of closeness with anyone else in their lives.

He told me of the anonymous death of an autistic man, who had a special relationship with his plumber. Being extremely parsimonious, he was particularly stingy about his water-heater, and feared spending even a single cent too much. Every day he would blow the flame out, fearing it was burning away a lot of unused gas. Sadly he was never able to reignite the flame, so every day, when he needed hot water, he would call the plumber to reignite it. Because the plumber understood the man’s condition, and knowing this system would actually cost him significantly more than he was trying to save, they worked out a deal. Each day he called, he paid only 10 euros. This was still significantly more than he would pay if he simply kept the water heater running..

He also told me about another man who fabricated the whole of his own history. Among the stories he told people is one about him as an important war hero with the resistance. His long lost family members however, said he had actually been working for the Germans. He kept on with these stories for so long that he came to believe them, and lived on in his own fantasy, in his own fabricated biographies. In the poem Starik wrote for him, he kept those fabricated stories alive and didn’t kill them off.

The Design

After you die, you sort of live on in marks you’ve left behind..in handwritten letters and notebooks…in old grocery lists…in doodles and scribbles… because handwriting is really someones second voice. Handwriting is personal, has a character that speaks for itself: a voice that is read instead of heard. Reading a person’s script, you can almost hear a person’s voice talking.

I wanted to make a sort of vending machine, containing unopened letters written by somebody that passed, so that the living could receive letters from the dead.

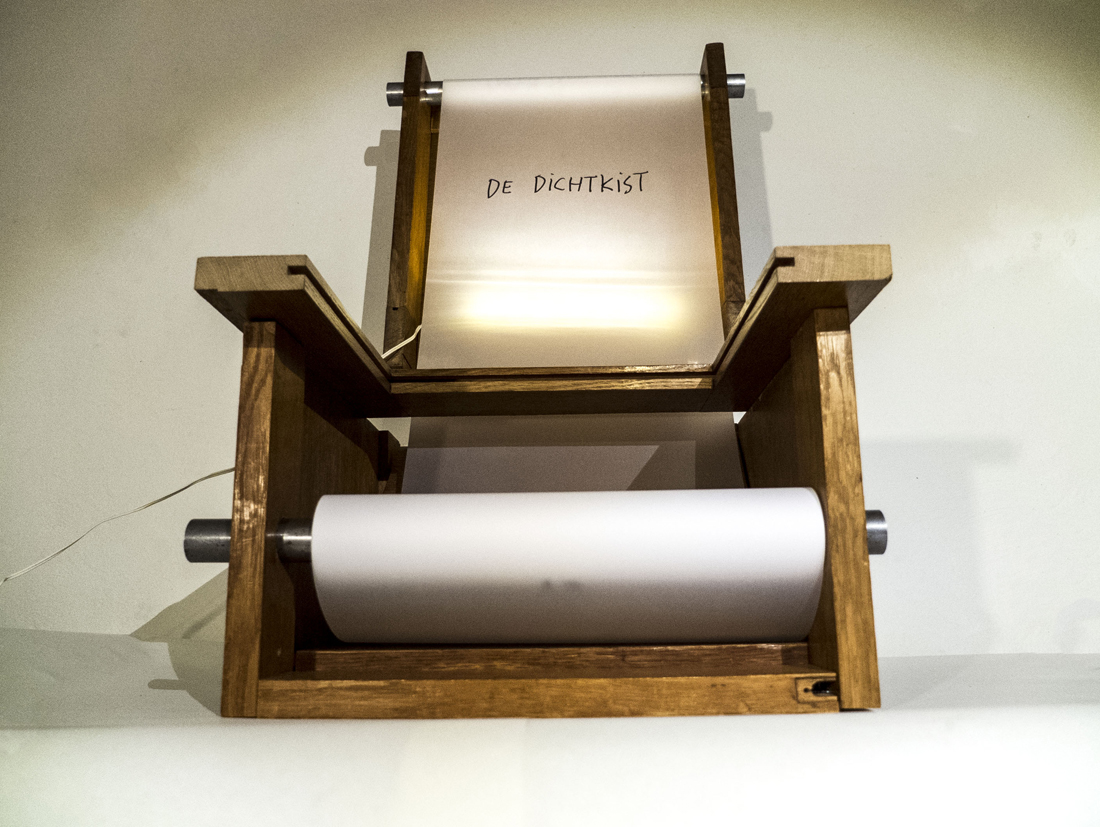

This transformed into the big turning of the wheels, and then to the transfer turning of a scroll from the bottom to the top. Inspired by Starik’s written canvasses, it became a sort of alter, displaying a composition of words.

De Dichtkist (translates into “ burial box with poems“) is a tribute: a coffin for handwriting, an open casket, a single space for the second voice and all of its marks to collect, and with a bit of turning, display. As it fills up, that turning can lead to a sort of conversation. The second voice can speak with itself. Built from the wood of century old doors, de Dichtkist houses the marked memory of lives that will some day, come to end.