In my quest to choose an object to research out of the current display of design at the Stedelijk Musem I initially thought I would go against my instincts. I thought small, delicate, rational. I even went as far as to write a full research on “small, delicate, rational” but after I was done I couldn’t go to sleep. Needless to say, my roots got the best of me and I ended up being hunted down by the work of Philip Eglin. To give a little background Eglin is an alumni of the Royal College of Art in London and he is specialized in ceramics.

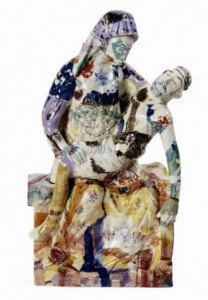

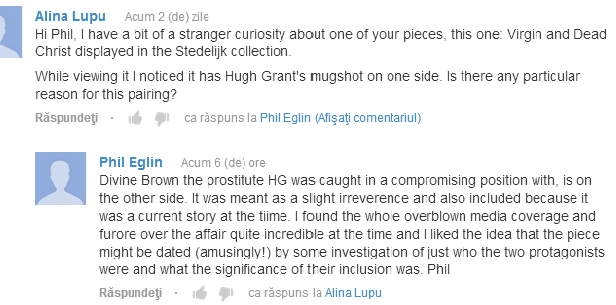

The work in question is entitled “Virgin and dead Christ” and it was made in 1998. The decade it was made in is so well embedded in it in fact that it has on one side Hugh Grant’s ’95 mugshot. Instinctually I wanted to know a bit more about the motivation for such a detail, and Mr. Eglin obliged me with a reply (in the age of rapid fire communication, artists apparently are kind enough to answer the curious):

Something as dated as this reference could now sound obsolete (in fact, it is assumed as dated), but in my view it’s delightfully reminiscent of the time when I was a kid and also of Romanian style of ceramics that I grew up with – not in the traditional sense, but in the purely kitsch one.

Easy to say that ceramics was never considered art in the country I come from. It’s purpose was either utilitarian (dishes, cups, etc), traditional (folkloric patterns) or of display on a smaller scale (think grandma’s living room, on a shelf).

My most prominent memory of ceramics is in fact the last one of the above since throughout communist times (until 1989) in Eastern Europe and even well after (old habits die hard) it was a custom to gift and later to show off in your vitrine figurines which made no connection to the surroundings of your living room and which were hidden behind glass for purely functional reasons (it saves on a lot of dusting hours). I suspect this was done because of the need to be sorrounded by beauty, but given the lack of education on the subject, never a true understanding of how to handle and consume said beauty.

The most common subjects which found their way into Romanian living-rooms were porcelains (named “bibelouri”, from the French “bibelot” or English “trinket” – which stands for ornament) of: random French couples dressed a la 17th century, random curved ladies in provocative poses, ballerinas large and small, peasants male and female, mythological figures, horses, peeing little boys, Christ and Madonna figures, dogs, chicken, weasels, bunnies and other furries.

The list was peculiar but standard. The objects, always poorly made, did not have any other redeeming qualities either than a striving for beauty and having been made of materials more delicate than plastic.

These tiny sculptures were never displayed as individual pieces, but crammed together. So, you would always see a bizarre Noah’s ark of larger than life dogs next to ballerinas and in a 17th century French setting in a 20th century Eastern European living room.

Seeing Philip Eglin’s work in the Stedelijk museum only later brought on the realization that I was, in front of “Virgin and Dead Christ”, catapulted back into a Romanian living room. The work screams contemporary through it’s eclectic mix of features on the two characters and patterns on their surface, but it also comes to me as a commentary against cleanliness and the rationality of Dutch design.

There is no reason, everything seems to have been pushed together against it’s will. The theme speaks of centuries of reinterpretation, during which the Madonna has been turned on all of it’s sides, so much so that now it’s impossible to have just one view of what the scene should look like. The subject has been done and done to death. Maybe that is why if it is to be done again it can only be done with a sly humour and a stamp of Hugh Grant’s face on it’s side. No longer can we look at it in reverence. The relation that we have with the image goes beyond “no judgement”, it’s also somehow pop culture in itself.

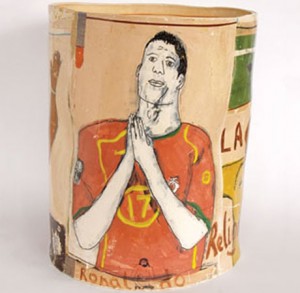

There are inspirations in Eglin’s work which are easily traceable” Northern Gothic religious woodcarvings, Chinese porcelain, English ceramics, contemporary packaging, popular culture. There is also a lot of humor as his later work (porcelains of the Pope, footbal teams etc) would go on to suggest.

Choosing Eglin has been for me an exercise in respecting my roots and disregarding the fact that they are not clean, solid, elegant ones, but messy and irreverent. After all, there is in design enough proof of cleanliness. A little chaos is therefore needed as well.

In retrospect the choice was also motivated personally by the stubbornness of both my parents to have a house lacking in ornaments. While I was familiar with the norm for Romanian living-room displays, I never did have any small ornaments, only one large library filled with books and records. In those small figurines as in Eglin’s work, I contaminated myself with a nostalgia for a time which I never truly lived, but only observed from a distance.