Among all of the recent books in the Rietveld Academie library, Boy Politics particularly appealed to me for its very peculiar aspect and design. It is a bit damaged and looks very breakable which gives it a feeling of preciousness, emphasized by the fact that it is a unique copy. At first I had decided to go see what it looked like because the title was very evocative to me and seemed like a topic I would want to read about. I am interested in the theme of gender and particularly male domination in different cultures and have often questioned it in my work last year in my art school in France. The boy figure, what is expected from a boy and how deeply these expectations and behaviors are attached to a culture and collective unconsciousness.

This book was my first glimpse of the tip of the iceberg that are Marc Roig Blesa and Rogier Delfos’ collaborative projects.

Boy Politics, Marc Roig Blesa and Rogier Delfos

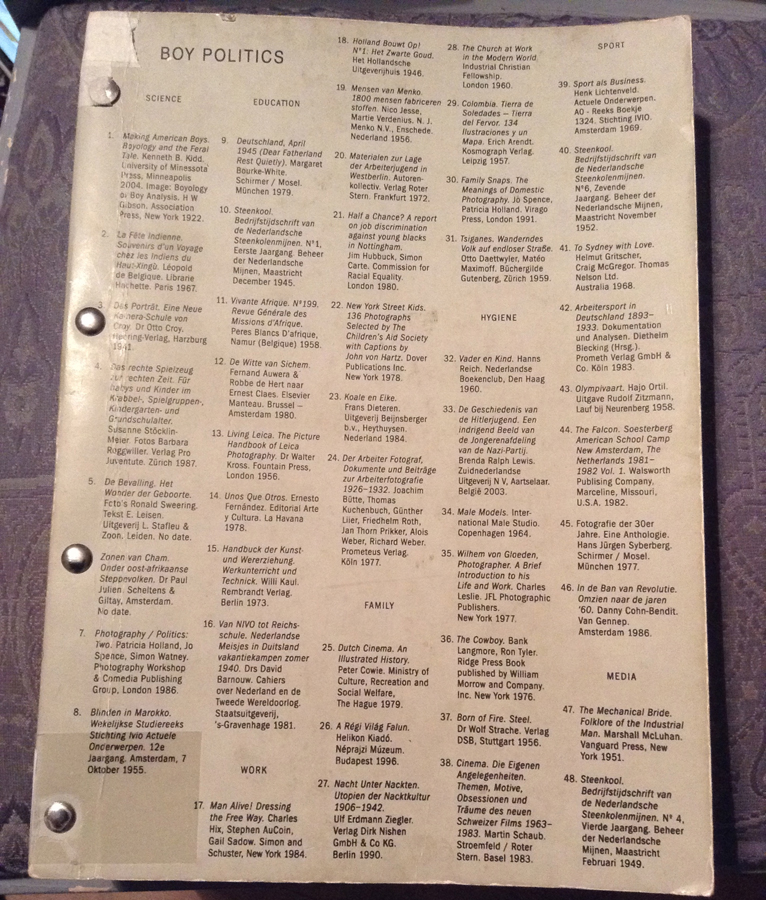

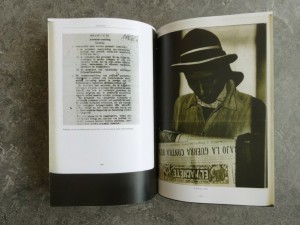

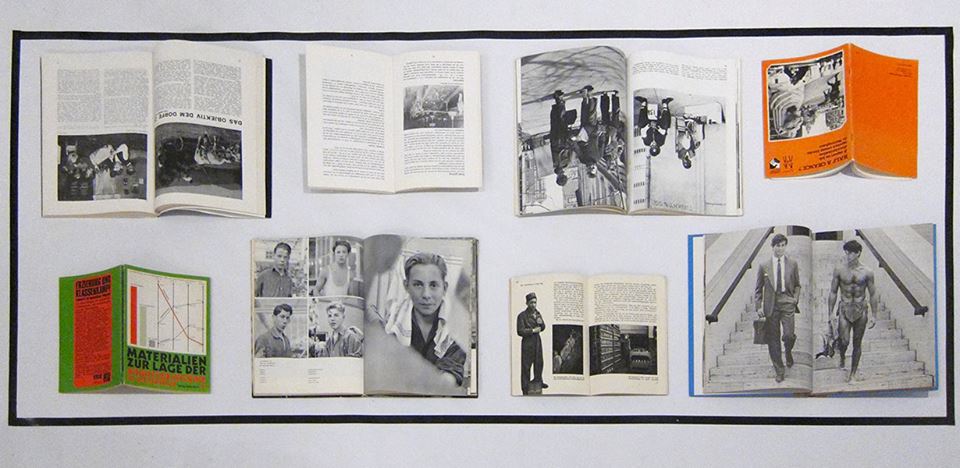

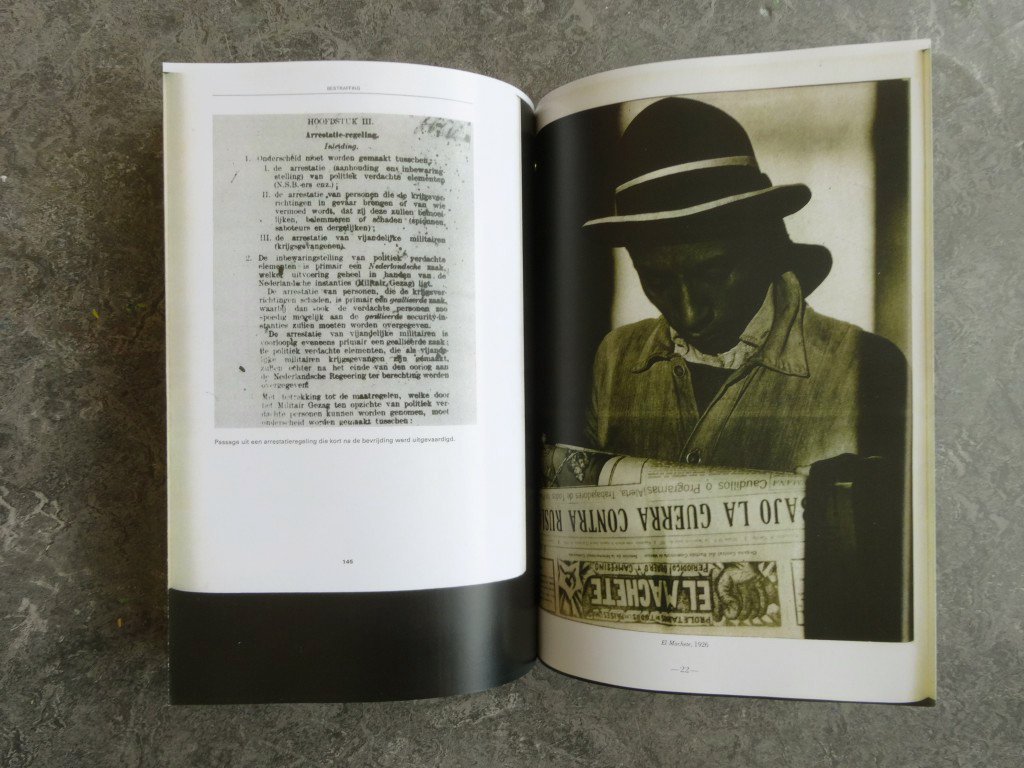

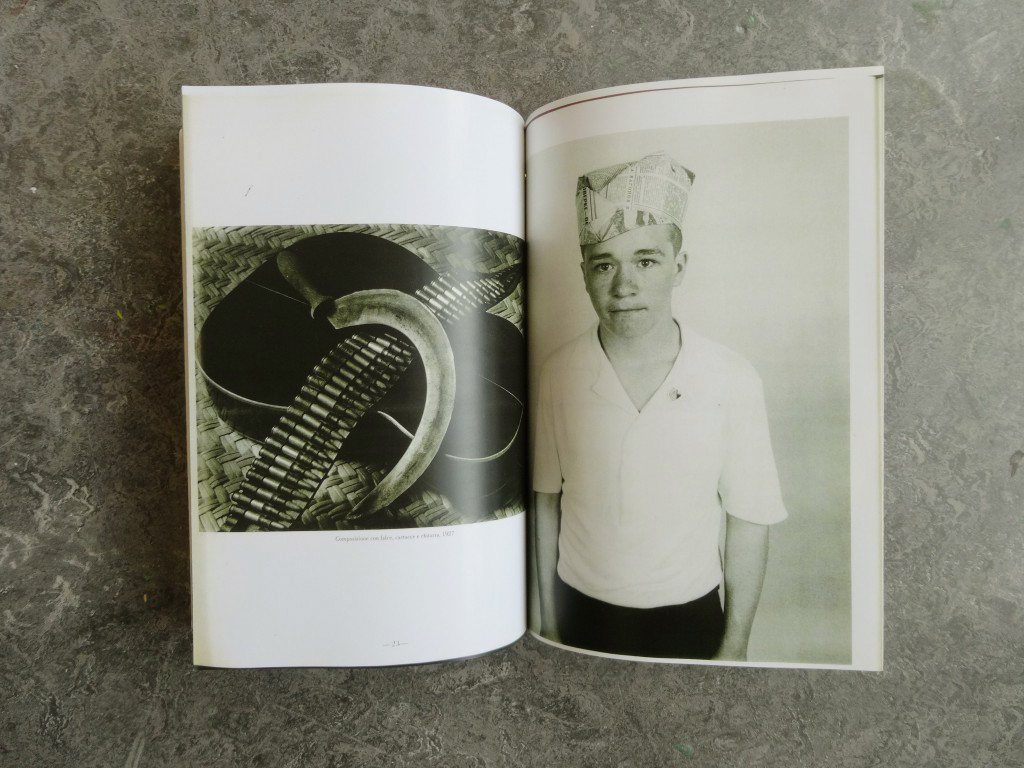

Marc Roig Blesa and Rogier Delfos are two former students of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Both graduated in 2009 ; Blesa from VAV and Delfos from graphic design. They have been working together ever since between Barcelona and Amsterdam. From 14/05/13 to 07/06/13 they held an exhibition at Rietveld library where they exposed a selection of Blesa’s secondhand books in a window display, opened at a certain page. It was a mute and powerful visual essay of the figure of the boy throughout images from the 1920’s to the 1990’s. Later on, two other former students of the Academie (Anton Stuckhard and Andrea Sergio) designed Boy Politics, a book that archives this exhibition in a very efficient manner that, to my opinion, is really coherent to the way Blesa and Delfos work. Without any fuss, they encapsulated the spirit of what was the starting point of a larger project that Blesa and Delfos have been working on ever since : « Werker ».

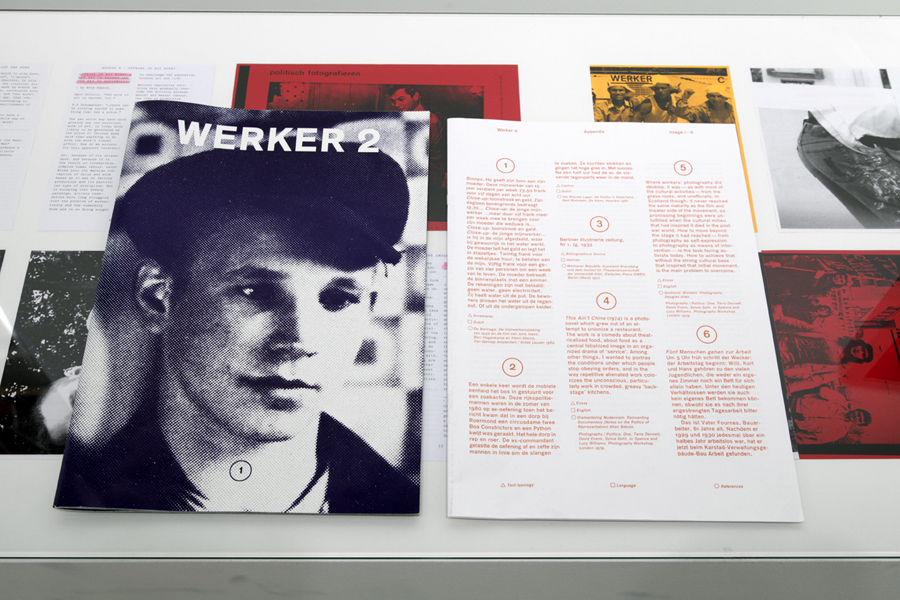

Werker magazine is a long term project and concept that asks many questions and got more and more complex over time. There are 8 different werker projects but usually more than one edition by project.

The artists define them as « contextual publications about photography and labor that inquire into the possibility of formulating a contemporary representation of work » They are all mute analysis of a situation that they try to depict in a most objective manner as possible. They are often the following or addition to an event (exhibition, lecture…) like for Boy Politics. Werker 2, for example, was realized for the exhibition « 1979, A Monument to Radical Instants » in the Virrena Centre de la Imatge of Barcelona (2011), dealing with the issues of daily life in crisis of working class young men. Knowing that photography is the medium that communicates best the essence of a situation, Blesa and Delfos have realized a very accurate observation of several situations.

An example of that accuracy is the « Cinema Diary » edition of Werker 6 (that you can find in San Serriffe book store, along with other Werker issues. It is « a collection of photo diaries that reflect on the current working conditions of the youth through self-representation and amateur photography. » It is the summary of a young artist’s (Matthijs Diederiks) side job at a Pathé cinema. In this small book (x) from which the cover is handwritten by Diederiks, you can find an extract of his working contract and meaningfulness in the lost time of a very boring job.

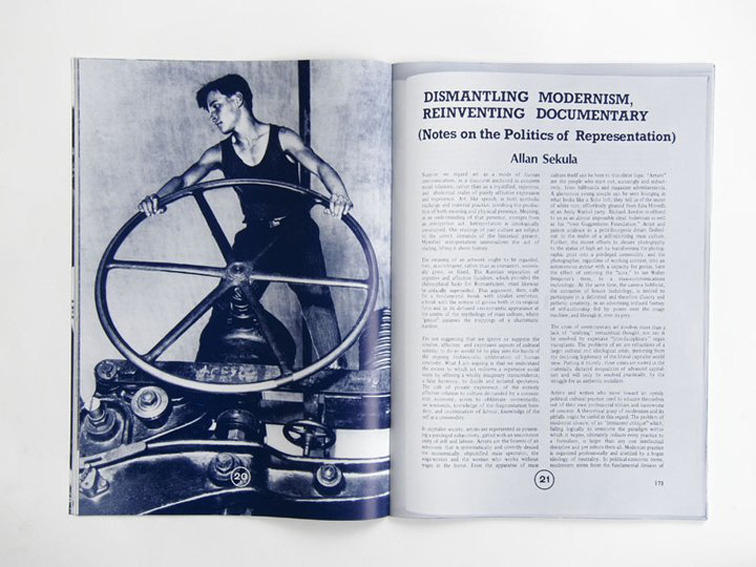

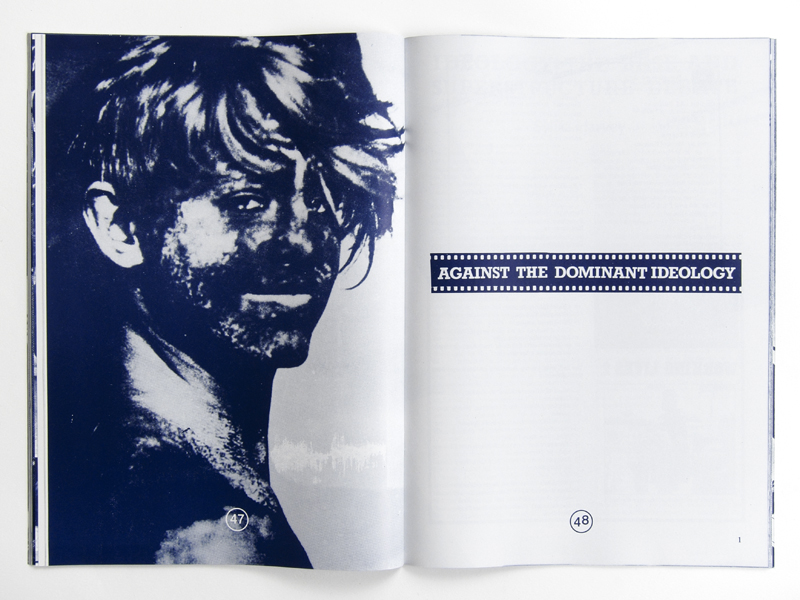

Werker is the story of how graphic design and art meet through photography (amateur photography, secondhand books images, internet pictures…) aiming to deliver a message : Images have power and that power is into the wrong hands, the people must take it back. Blesa and Delfos are indeed strongly politically engaged with revolutionary ambitions.

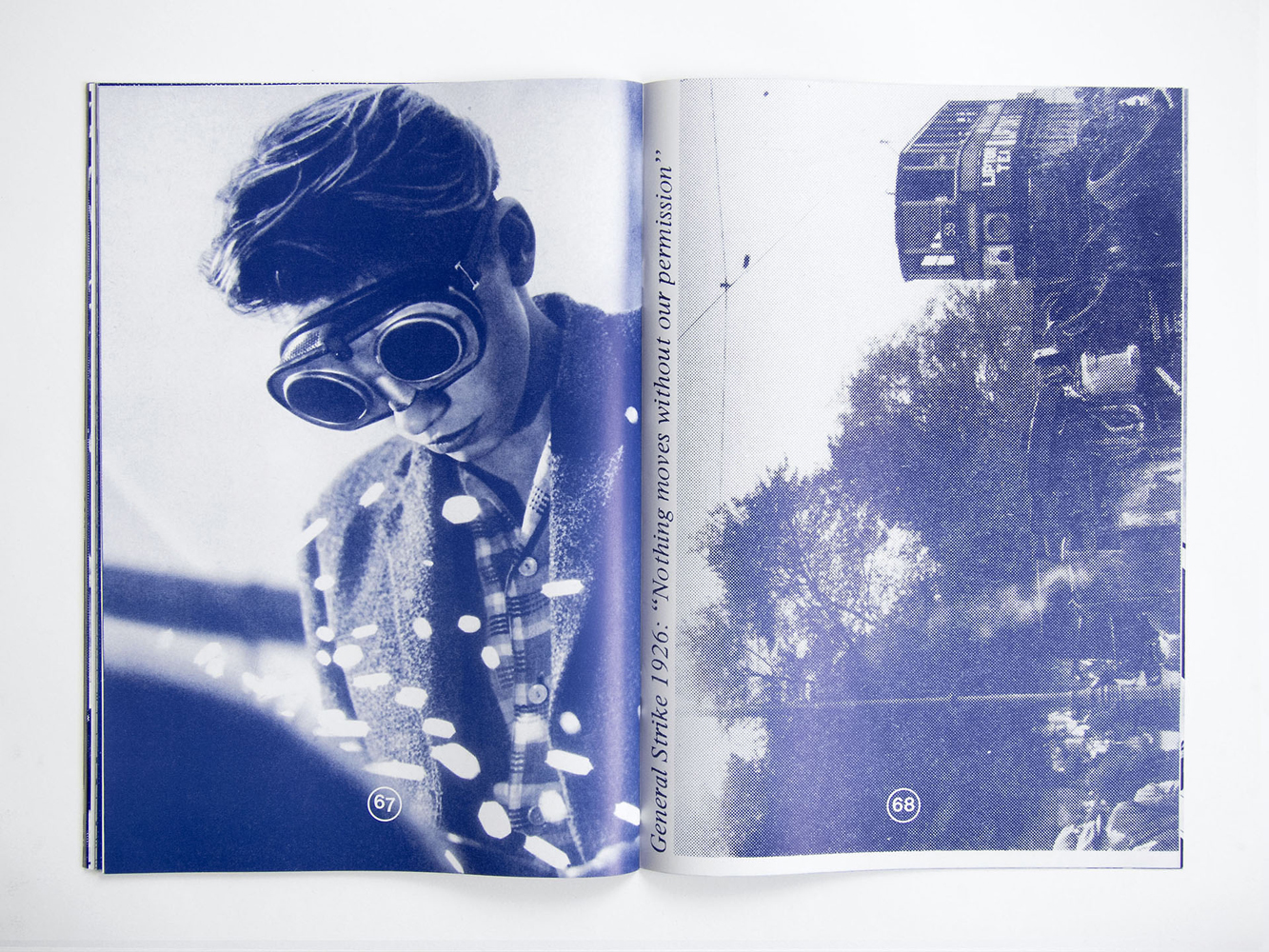

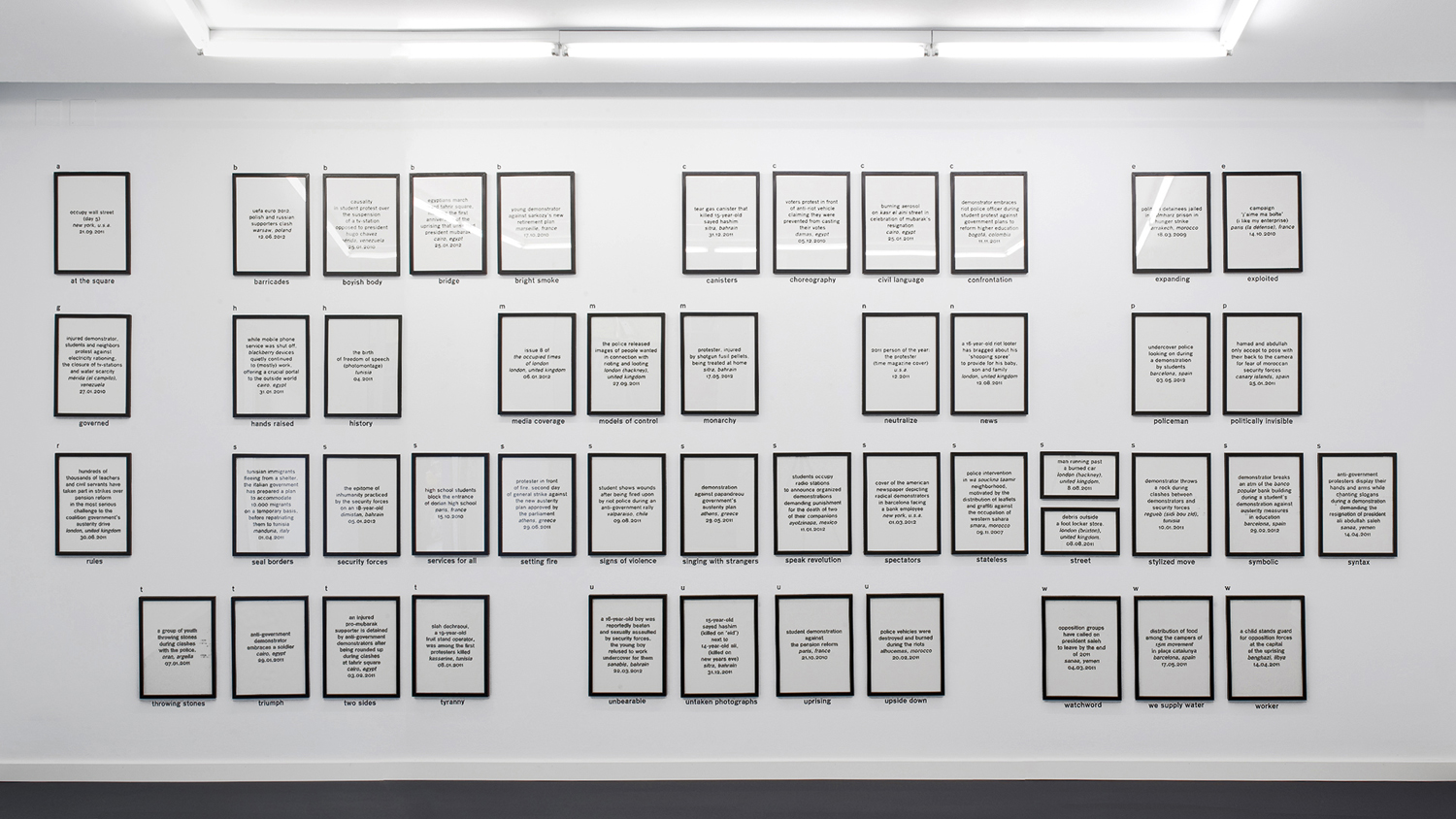

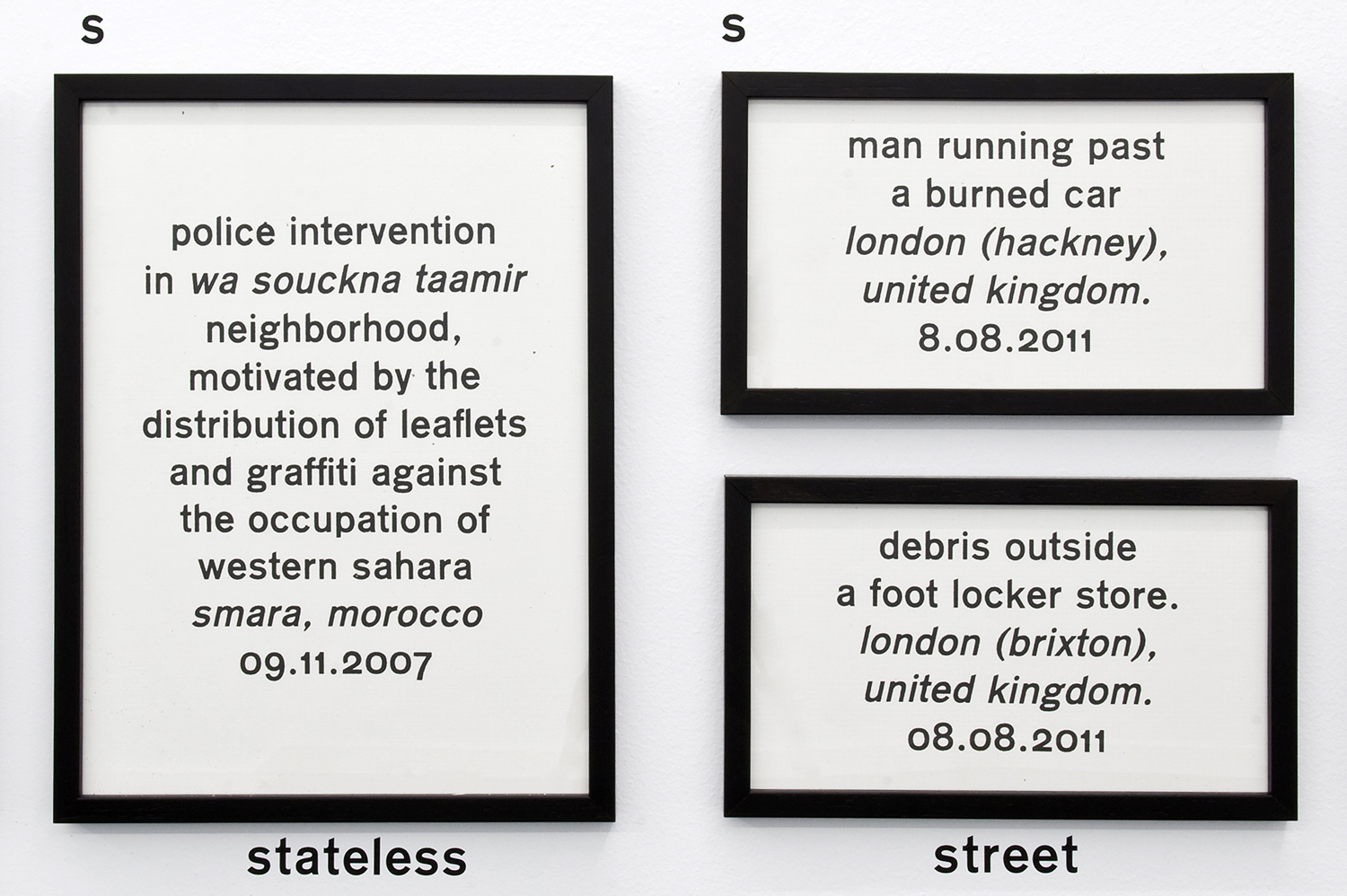

Let’s focus on « Werker 7 : the language of revolution ». This exhibition followed by an edition of newspaper (once with and once without image) was inspired by the words of Ariella Azoulay in a lecture she gave at the museu d’art contemporani de Barcelona in 2011 in which she did an analysis of Egypt’s revolution through images from the internet (you can find her lecture here : x). Werker 7 questions the revolutionary image, the revolutionary language, the role of mass-media in all this and the function carried out by photography in construction of a global revolutionary language. All the images chosen for that project were found on the internet.

Werker takes its name from the « Worker Photography Movement » : a group of amateur photographers that appeared in Germany in the 1920’s, following the steps of the first socialist photography experiences in the USSR which extended into the rest of Europe, the USA and Japan. The first group of amateur photographers to use the camera as a tool to fight class-struggle. When I found out about this origin, the work of Blesa and Delfos came clear to me to its full extent. Werker 3 is a « political kitchen calendar » developed within the « grand domestic revolution – user’s manual », a long term living research initiated by casco office for art, design and theory in Utrecht. it is a call for students, artists, domestic workers (and so on) to contribute to the collective gathering of materials. A call for amateur photography as an observation of domestic space. The assignment was « Think politically of your domestic space and contribute to Werker 3 ».

Finally, I found in the « Cinema Diary » an extract from the book Der Arbeiter-Fotograf from Willi Münzenberg (1931) that I thought was very relevant to Delfos and Blesa’s approach, aims and tasks.

« Photography has become an indispensable and outstanding means of propaganda in the revolutionary class struggle. (…) For an illustrated book is easier to read (…) than the lead article of a political daily. Photography works on the human eye (…) the bourgeoisie caters for the mental laziness of the masses and also makes a lot of money. (…) Much more important is the political effect (…) a skillful editor can falsify every photograph into its opposite and can influence the politically naive reader. (…) The revolutionary workers of all countries have to realize these facts very clearly. They have to fight the class enemy with all means. Just as the workers of the Soviet Union have learned to make their own machine-tools (…) the proletarian amateur photographers have to learn to master the camera and to use it correctly in the international class struggle. »

Delfos and Blesa’s aim and ambition : an anti-propaganda revolution guided by photography.

Rietveld library catalog no : roi 1