Photography: A Reproduction

Johannes Schwartz’ exhibition Blue, Turning Grey Over You at the Annet Gelink Gallery [x] shows photographs of photographs that Piet Mondrian took from his paintings. In other words, Schwartz’ works are ‘reproductions’ of reproductions. Nevertheless, one should note that Schwartz’ intention goes beyond documenting or copying art works. While Mondrian argues that photography is mainly suitable to imitate art works rather than to be an art form itself, Schwartz proves otherwise by depicting Mondrian’s reproductions, address book and records in photographs exhibited as autonomous art works. Hereby, Schwartz positions himself in a greater debate in the history of photography. The tension between photography as document and personal expressiveness has been the core discussion concerning the status of photography as art.

Nowadays it seems self-evident that photography is seen as art form. This, however, has not always been the case. There was already disagreement on the artistic potential of photography in the 19th century, when the medium was introduced. Nevertheless, it had by far the same recognition as painting. Moreover, photography was often considered a mechanical – rather than an artistic – practice. A century later the distinction between technology and art was put in question. The Bauhaus artists had a multi-disciplinary approach and aimed to integrate design, art and modern daily life. This questioned the position of photography and lead, particularly in Germany, to a highly topical debate during the 1920s. The Bauhaus artists considered photography, as product of modernity, suitable to depict this Modern Era. This was also stressed out in the article “Painting and Photography” (1927) by Ernst Kállai, editor of the Bauhaus Journal i10. Even though Kállai admitted that painting was a higher form of art, the Bauhaus’ approach on photography was still quiet controversial at the time. The Frankfurter School theorist, Walter Benjamin, claimed that art works have a certain authenticity or aura which photographs –whether a mechanical reproduction of a landscape or an artwork – do not have (1935). Mondrian wrote a few lines about photography that comment on and contradict Kállai’s article (1927)[x]. He considers the medium, as Benjamin, a mechanical practice suitable to imitate or reproduce objectivity. He did not value the creative or artistic potential of photography. Mondrian made reproductions for albums that enable him to show and explain his paintings. After that it was no longer necessary to explain the development of his work in his studio. This allowed him to show only his latest painting. Hence, photography was not used as an artistic expression, but as a tool to establish himself as an artist. Interesting is to add that there were only black and white photography at the time, which forced Mondrian to describe the colour composition of his work in the albums as well.

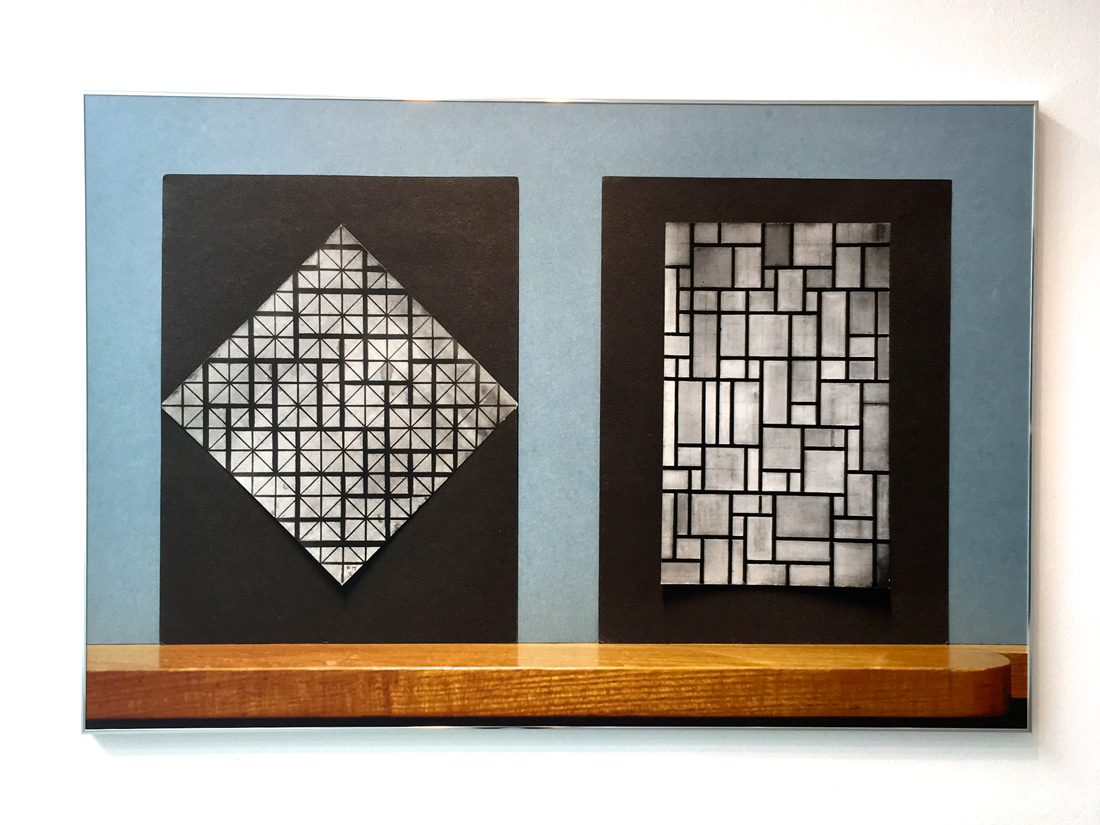

Johannes Schwartz PM #2, 2017

Johannes Schwartz saw Mondrian’s albums along with other personal belongings at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RDK), when he was asked to document them for a magazine. This gave him the opportunity to see objects that are normally are not publicly accessible. Schwartz was particularly fascinated by the albums, which demonstrated the motivation and working drive of the artist. Mondrian took great effort in making high quality reproductions and describing the paintings carefully. The limitations of the medium at the time – e.g. being in black and white – did not seem to bother him and instead he found ways to overcome them. Schwartz got interested in creating a possibility in which more people would see Mondrian’s work attitude. However, his goal goes beyond documenting the objects for an exhibition. Instead, he plays with the (re)presentation of them. Mondrian’s reproductions, for instance, are photographed in colour and put on a wooden shelf with a blue-grey wall in the background. In one work different ‘reproductions’ are grouped in one line, noticeably build up from different pictures photoshopped next to each other. All these characteristics remind the viewer that the photographer took different decisions and actions in the making process. The latter raises questions that refer back to the central debate. It also doubts Mondrian’s position [x]… Do reproductions have the capacity to imitate or reproduce objectivity? Can photography in itself be objective or do the choices of the photographer inevitably evoke subjectivity? Does the intention of the photographer decide whether it is a document or an artwork? These questions, from the many one could ask, put the earlier mentioned discussion in a contemporary context. The visual aspects of the photographs add a conceptual level to the works, which differentiates them from reproductions that are merely meant as a copy. His work aims to intellectually activate the viewer and invite him/her to make associations, reflect and take a position in the debate. One can also go a step further and state that the works themselves provide an attitude towards photography. The exhibition shows that throughout the centuries, photography has developed to be part of the visual arts and that a conceptual level allows reproductions of reproductions to be autonomous works of art.

A video reproduction of reproductions of reproductions

When visiting the exhibition, I started to think about the role of photography in general and the fact that the medium has never been as accessible as it is today. Everyone can take pictures and videos with their phones and share them globally. This consequently raises new questions about the relation between photography and art. In this train of thought, I filmed my gallery visit on my Iphone. The voice-over is a fragmented reproduction of a conversation I had with Johannes Schwartz about this exhibition.