Have you ever heard about theosophy?

We didn’t either, but check out this article because then you’ll know how it influenced Mondrian and Rietveld’s work.

Theosophy– what does this even mean?

It is a unity of Religion, Science, and Philosophy that combines a variety of belief systems in its search for an underlying universal harmony. Basically, it is everything, therefore you have to be very focused to understand what specific ideas it defends and how is this shown or practiced in art and life in general.

It is also a doctrine of religious philosophy and mysticism (so it isn’t a religion itself), but holds that all religions contain elements of truth.

Theosophical writers hold that there is a deeper spiritual reality and that direct contact with that reality can be established through intuition, meditation, revelation, or some other state transcending normal human consciousness.

Theosophy has influenced many artists among whom were Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Gauguin, Malevich, Gerrit Rietveld (and some others from De Stijl movement) and Pollock too. This beliefs played a crucial role in the work of this artists, whose works were seemed to search for the understanding of spirituality.

All in all, theosophy seeks to integrate perception and thought, the natural world and the spiritual work, science and religion.

How did theosophy influence De Stijl

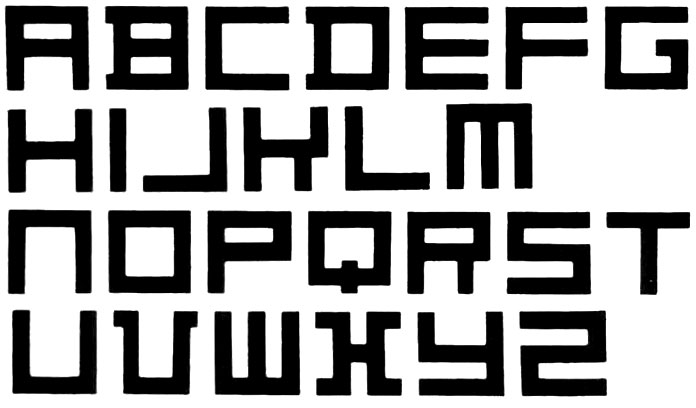

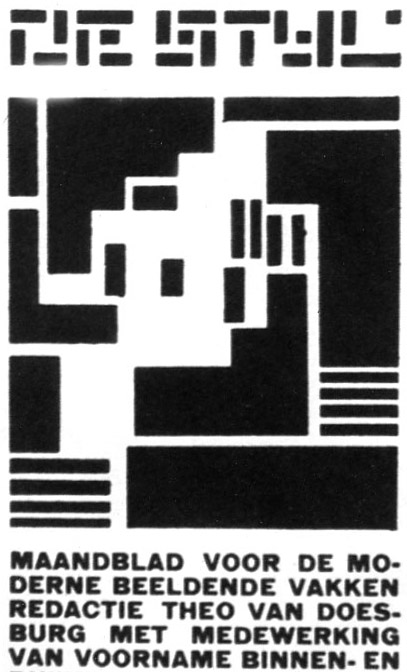

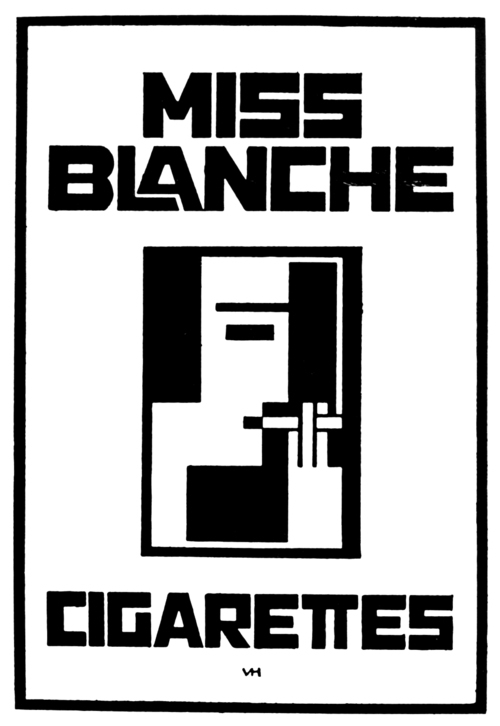

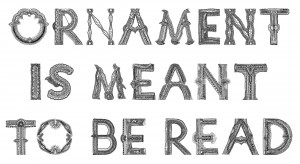

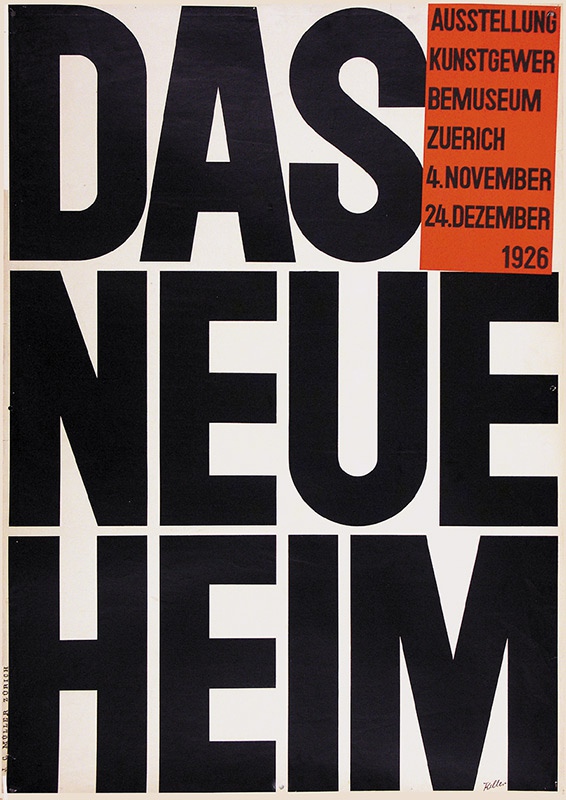

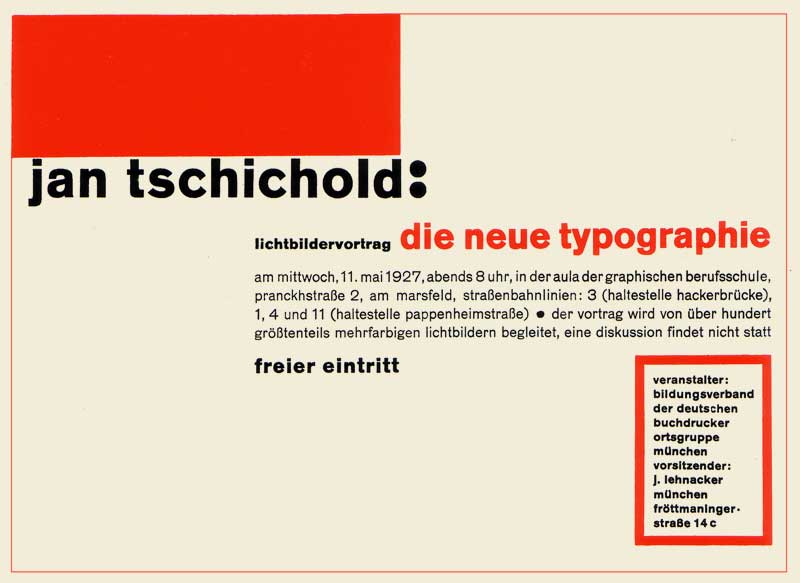

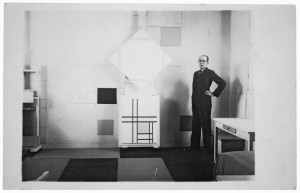

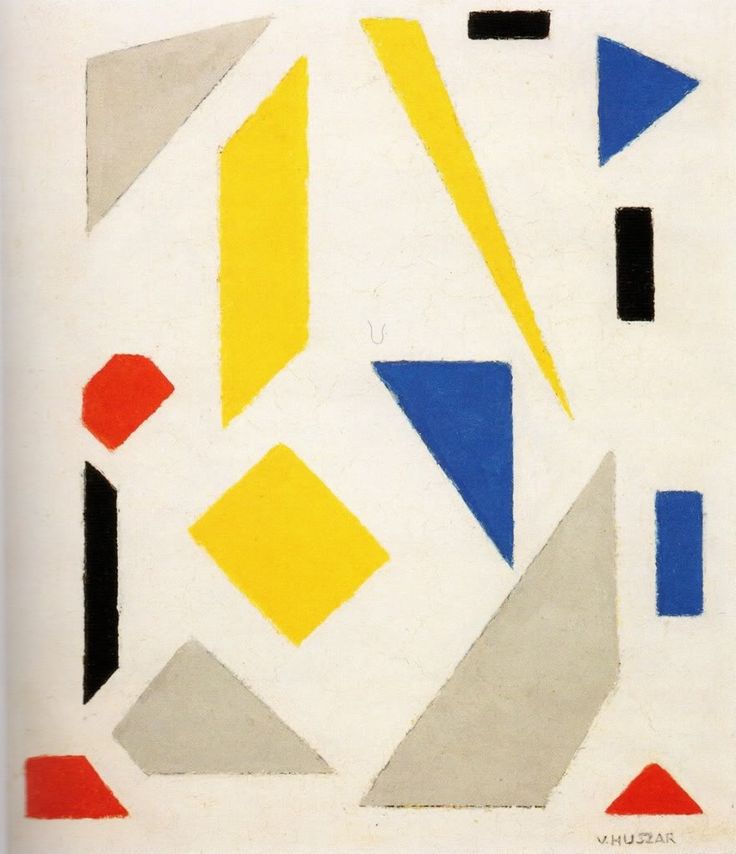

De Stijl magazine was publishing the group’s design work combined with theoretical writings which also contained mysticism. Members were deeply influenced by theosophy which was also an important part of Bauhaus. You can see that in the way they rejected any form of naturalism in favour of a formal abstraction that connected the movement with Russian Constructivism.

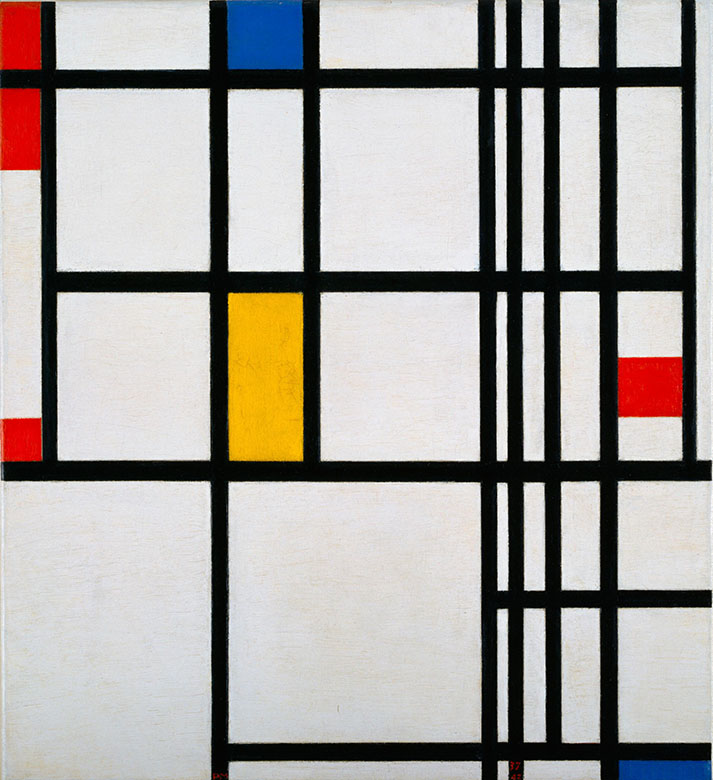

De Stijl group wanted to create a new kind of art, architecture and design in order to raise a disillusioned humanity from the horrors caused by World War 1 and as many artists throughout Europe, they attempted to liberate the arts from tradition. They wanted to change art from individual to ultimate, universal. Their vision was based on deconstructivism – reducing the universe to fundamental elements and forms – the vertical and horizontal lines became the symbols of universal harmony, to which were added primary colours red, blue and yellow along with black, white and gray (considered non-colours). Even if you don’t understand the deeper meaning of theosophy, these are the things you can recognize in artworks of De Stijl movement.

Anyways, members were aiming towards geometrical and technical art which would be an experience as a whole. They were trying to give art a spirit of forms and mystification.

What was important for them was purity in architecture, the absence of organic and personal forms. Like theosophists, members of De Stijl believed in the presence of deeper spiritual reality, whereas a direct contact is established through a state transcending normal human consciousness. They brought a sense of material, intellectual and spiritual unity to art, architecture and design.

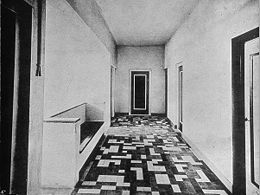

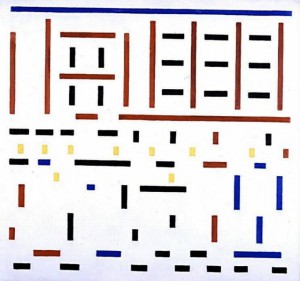

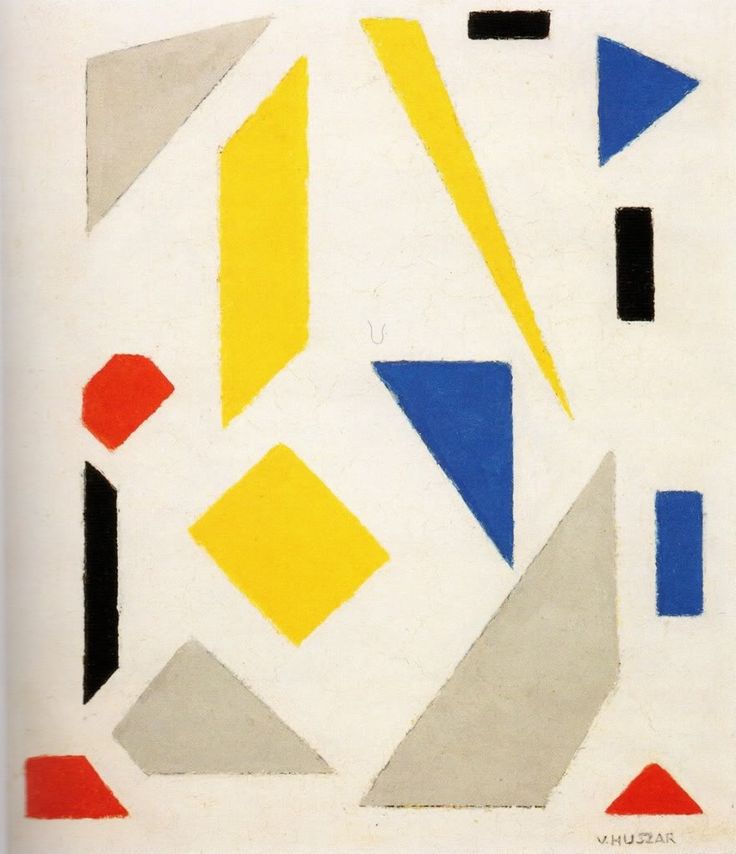

Theo van Doesburg’s work related to Neoplasticism – a work from Vilmos Huszar

<

Mondrian as a member of De Stijl

His path to Neoplasticism

Mondrian intensified gradually his expressive manner of painting and began to have a more and more intensive use of colours, that eventually lead him to the need to depict the visible aspects of reality.

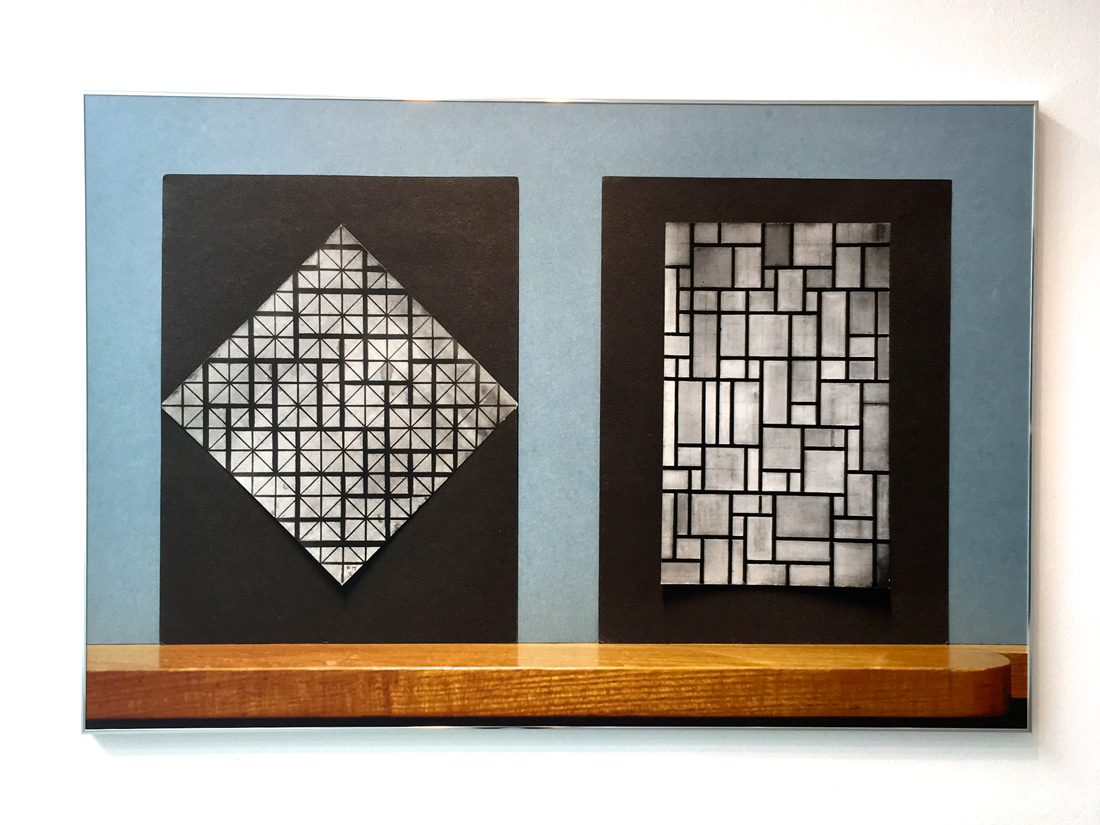

From 1908, Mondrian began to work in search for a truly form of painting. The artist came to the conclusion that the pure, intense, inner colours (the primary colours) and a simple manifestation of the line (horizontal and vertical) could help reach an abstract form of art that would be suitable to the spirit of the new modern age.

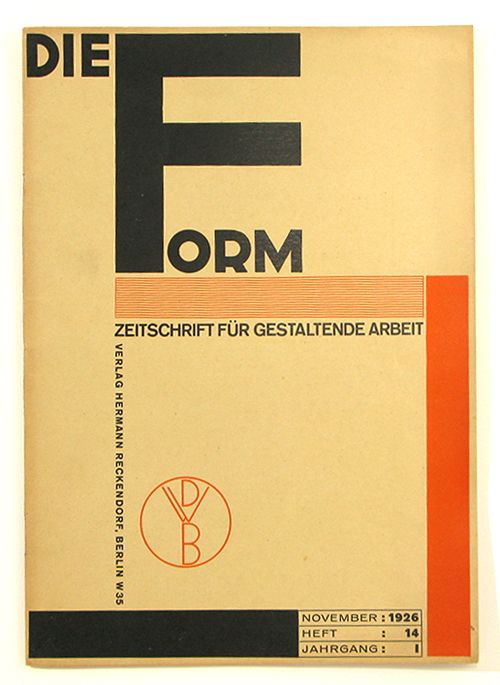

In 1917, Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg founded the group De Stijl. Mondrian used this magazine as a vehicle for his ideas on art, and it was actually in the magazine where he defined his aims and the term Neoplasticism. Though Mondrian established his only visual manifestation/painting style: Neoplasticism, based on philosophical and moral considerations associated with theosophy, this name was also applied not only for his work, but also for the art that the De Stijl circle practised in the different areas.

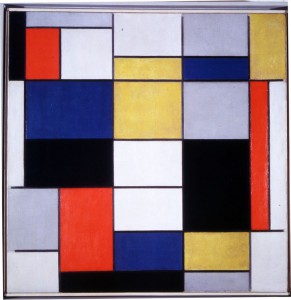

The intention would be to use the form and line to reduce the visible reality to its essence. So, in Neoplasticism, all the abstraction is connected with the reality. The elements are displaced from their visible form, but reflected in an abstract dimension.

As Mondrian himself considered:

”As a pure representation of the human mind, art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form. The new plastic idea cannot therefore, take the form of a natural or concrete representation – this new plastic idea will ignore the particulars of appearance, that is to say, natural form and colour. On the contrary it should find its expression in the abstraction of form and colour, that is to say, in the straight line and the clearly defined primary colour.”

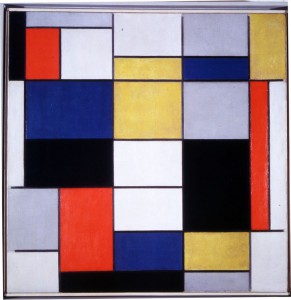

Mondrian uses the basic elements of painting: line, form and colour in their purest, most fundamental state, creating compositions with different lines and planes, verticals and horizontals, neutral and primary colours in a universal visual language that everyone could understand intuitively.

Two years later, the architect- designer Gerrit Rietveld joined De Stijl, which had a significant impact on the Neo-plasticists’ ideas and production.

Influenced by theosophy’s ideas, Mondrian reduces all elements to straight lines that cross and form various sized squares and rectangles and restricts the palette to pure neutral primary colors and black, white and grey. This was his proposal to represent the universal order, rather than the physical meaningless world.

Modrian’s texts on Neoplasticism

How is Neoplasticism connected with theosophy?

Piet Mondrian was raised in the protestant church and later on, in 1909, joined the Dutch Theosophical Society, which was one of the main spiritual movements in the Western society at the end of the 19th century. This Society was founded in the United States but quickly spread throughout Europe and had an immediate influence on art, particularly in the Netherlands. In fact this influence was so visible that forty Dutch artists participated in the exposition organized in 1904 in Amsterdam for the Theosophical Society’s International Convention.

From this time on, theosophy was to be a major influence in life and work of Mondrian.

In the journal De Stijl [x], Mondrian published some articles about the influence of Theosophy. In this articles, the artist analyzes the role of traditional art that he considers as a consequence of the lack of harmony inside of man (conflict between matter and spirit) and the imbalance between man and nature. For Mondrian, theosophy was the answer to this imbalance. Theosophy principles could, in his ideas, bring consciousness of the self, and as a result, bring the harmony in this relations.

For him, when the consciousness of individuality or, in other words, the concept of spirit emerges, two conflicts emerge with it. The first one would be the conflict between this individual spirit and his physical body. The second one, as a consequence of the first one, is a confrontation between man and nature, generating a ‘disharmony between man and his surrounding,’ or simply ‘the tragic in life’ as the artist considered.

In this way, we can consider that Neoplastic art arises from the same principal as traditional art does- from the perception of an imbalance inside of man. However, Neoplastic art tries to represent an absolute truth directly: the idea that if the artist represents it, is because he knows it, and not just some partial and accidental truth as traditional art seems to do it.

The aim of Neoplastic art is the representation of the absolute, almost like religion. By reaching this goal, he would be able to help the common man finding his inner balance. How? Modifying the external world to another one capable of bringing some inward balance: by transforming the surrounding environment, he would transform the man itself, and consequentially the society.

“Art –although and end in itself, like religion– is the means through which we can know the universal and contemplate it in plastic form.” (Mondrian, 1918)

Neoplastic art’s objective is to restore in man a balance with his environment, lost when man gains consciousness of his own individuality. Neoplastic art should be dissolved and fused into and with life.

For the artist himself, neoplastic art shouldn’t be limited to painting but rather extends to architecture and urbanism, and in this way make a real change in the environments. Mondrian considered that each artistic disciplines should perform a specific role, and together they should reflect the common harmony of the universe.

Therefore, for Mondrian, painting’s task would be to act as the guide for the rest of the other disciplines and eventually be dissolved, if the task is successful, into architecture, urbanism, life.

We can consider that theosophical beliefs are expressed in Mondrian’s neoplastic work, both, theoretically and concretely, in a constant demand for a true theosophical art.

Art is, in this way, a reflection of the absolute, “the Radiating Center” (as Theosophy calls it), which is the original force, creator of everything (idea that nature and spirit are manifestations of the same original whole: universal/cosmic order).

The artist, thereby, is the “translator” of a higher reality, and his works must repeat the representation of this “Radiating Center”.

Art should reproduce the conflict between opposing elements and the solution for that same conflict. The image of harmony cannot be static, but represented by multiple dialectics: two levels of elements, among which, simultaneous oppositions are produced (line/plane, vertical/horizontal, female/male, color/colorless…) The universal force/cosmic order/ the harmony, is so expressed in the duality between this contrasts.

While searching fot the harmony between opposites, Mondrian aims to help common man access his own inner harmony. By transforming the entire natural environment, the artist would establish the balance and reflect the image of the common origin of all creation: of the absolute. In this balanced environment, the common man can reach his inner equilibrium.

Composition A, Piet Mondrian (1920)

Gerrit Rietveld as another member of De Stijl

He was born in Utrecht in 1888. His father was a cabinet maker and when just a little child, Rietveld joined the family workshop. His apprenticeship was steeped in the traditions of the Arts and Crafts movement which can be seen in his early work (first attempts of furniture design).

In 1911 he opened his first shop in Utrecht and started studying architecture. As many others, he was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture. By 1919 he became a member of De Stijl and became friends with its members Huszar, Theo van Doesburg, Robert van t’Hoff and others.

What influenced Rietveld’s work?

Theosophy played a major role in Mondrian’s art, but since Rietveld was a member of De Stijl too (although he never actually met Mondrian), we can also see the influences of the proclaimed philosophical ideas in his work.

In De Stijl architecture and design, Cubism was again influential but so also were Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie House designs, with their asymmetric free-flow of interior and exterior spaces. Despite all that, Rietveld’s ideas were more down to earth and less philosophical that the ones of Mondrian and Doesburg. He didn’t speak frequently about his work. Therefore the interpretation of it is based on the more philosophical tenets of the other De Stijl artists (members were very different considering a way of thinking) and it sometimes seems as if the designer’s voice may have been overshadowed.

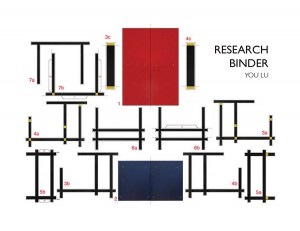

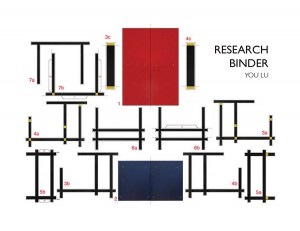

Rietveld’s painted Red/Blue chair became the archetype of the movement, it was also the first time that the De Stijl colours, usually used 2D, (on Mondrian and van Doesburg’s paintings) were applied to a three-dimensional object. It was the first major piece of furniture to accord with the movement’s principles – conceived as a spatial composition, conspicuously disregarding comfort, traditional construction techniques and concepts of decoration (built on a series of horizontal and vertical planes, provides a clear expression of the group’s ideas).

Gerrit Rietveld: Red and blue chair

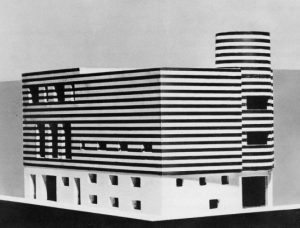

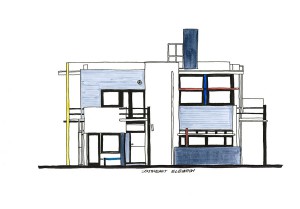

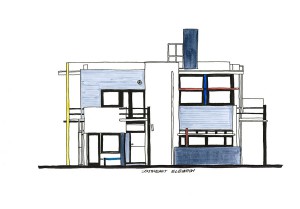

With the Schroder’s house Rietveld created a totally original vocabulary in building construction and in the treatment of interior living space. The complex, asymmetric cubic construction of horizontal and vertical planes and lines encloses and releases space in a three-dimensional equivalent of a Mondrian painting. Linear elements are red, blue, yellow or black; surfaces white or grey.

Gerrit Rietveld: Schroder house

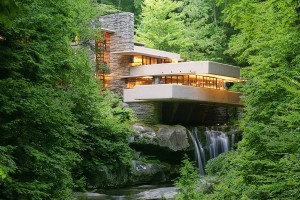

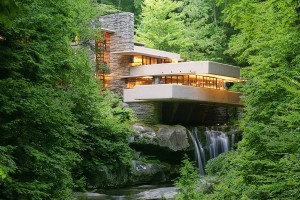

A major effect on Rietveld was also Frank Lloyd Wright’s work who was a functionalist and a part of an International style. The most influential details from his work were the flow he produced between interior and exterior and also the use of verticals and horizontals. You can also see that in Rietveld’s last work, Gerrit Rietveld Academie where glass surfaces are made in a way you can see through the building, therefore it merges with surrounding nature.

Frank Lloyd Wright: Fallingwater Frank Lloyd Wright: Robie house

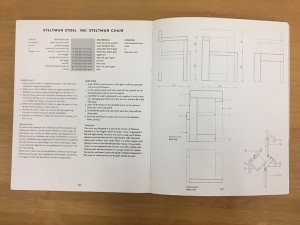

While quickly recognized as a major contributor to the development of Modernist architecture, interior and furniture design, Rietveld’s later work was largely confined to furniture design. Most known examples are his tubular steel and wood Beugelstoel chair, wooden Zig-Zag chair and wooden Crate chair. Among his other design work was the Netherlands pavilion for the 1954 Venice Biennale and a sculpture pavilion in Arnhem, Holland, built in 1955.

His furniture was designed for a mass production to be available to a large audience, even though at the end is wasn’t mass produced nor standardized – no two versions had the same dimensions.

It’s funny how when you see buildings, you mostly don’t think about the theoretical background of their form. Until we started making this research, we were more focused on functionalist features of buildings and which movement or era they belong too, but now we find ourselves thinking: ” Do this shapes represent some philosophical ideas?”

To conclude …

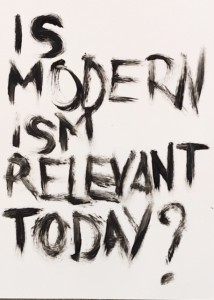

It’s interesting how the abstraction of Mondrian and Rietveld’s work seems to be so far from theosophical ideas – when you see the chair or a painting you don’t make an instant connection.

Mondrian and Rietveld both seems to try to make art that could reach the majority of people –a painting that would have an universal meaning (Mondrian) and a furniture that would be available for masses (Rietveld) – Art for everyone, art that would make life better. In a way, one can consider it an utopian idea, since the majority of people does not really understand the theosophical thinking … So the question remains: How educated should someone be when experience their art? Or in other words, to what point do you have to be aware of the purpose of the work to have the full experience of it? [x]

Now you know. Awesome, isn’t it?

a cooperative research by Neza Kokol and Carlota Bóia Teixeira Neto