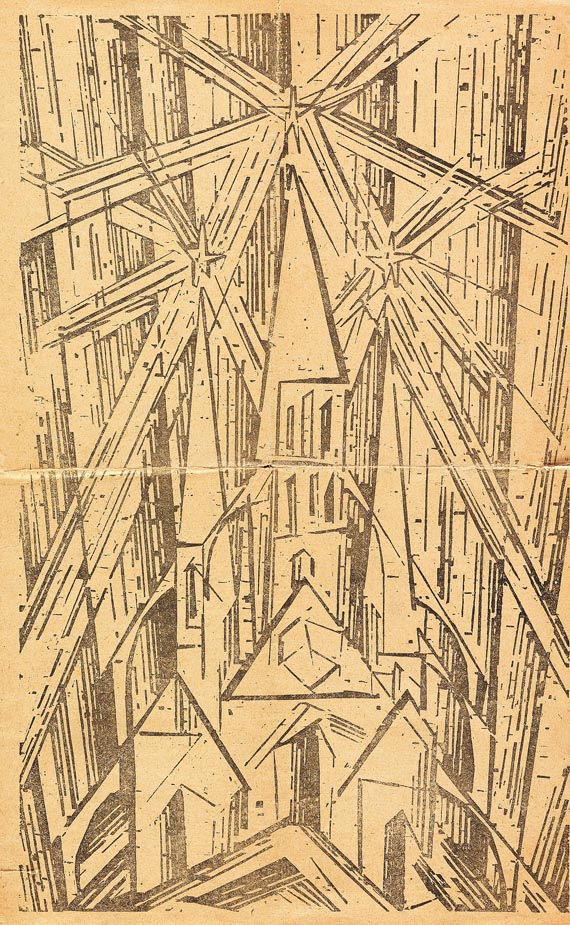

The Bauhaus manifesto published in 1919 outlines basic traits of the school. Headed with the Lyonel Feininger Cathedral (Kathedrale), the reader faces three stars shining above the turrets of the fictional basilica.

Lionel Feininger, Kathedrale, 1919, Cover of the Bauhaus Manifesto.

Programme of the Bauhaus.

The three stars are said to represent the main three elements of painting, architecture and sculpture. All of which fall under the main concept of ‘building’. The Bauhaus was dreamt up upon a basis of creatives coming together, in alliance. To build work in an evolving space, a cathedral of mucky boldness, master among student, declaring craftsmanship and building as the basis of all learning.

Bauhaus itself is a blend of the word ‘to build’ and ‘house’. It takes semantic place as a ‘building house’. Now we can see the offspring of the school stretching from Berlin to Chicago, Pittsburgh and the Netherlands. Amsterdam is home to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, which too was birthed from the wave of Bauhausian teachers and students left itching to scatter and inform after the original disbanded.

The school, mostly founded on modernist[1] design still has it’s reverberations. Is it just names that live on? Is the branding of Gerrit Rietveld, the only thing that links us to it’s educational model origins? Or is there still a cry of modernist education professing ‘building and making’ over all students?

It occurs that in the postmodern[2] world, the act of ‘building’ is seemingly scattered. Questioned theoretically. Few are painters, sculptors or architects now. Monogamous artists are perhaps becoming a thing of the past, steadily becoming toast along with craft in art. Perhaps we aren’t building physical practices anymore – emerging in the form of degree courses like ‘Autonomous Sculpture’ surfacing at the Rietveld, a subject so loose – almost transient. The focus here is on concept, as opposed to physicality.

The original Bauhaus manifesto is not something that presents a package of transience, but one of definitive action – “Architects, sculptors, painters—we must all turn to the crafts. … The artist is an exalted artisan.” The stress is on doing. Less on thinking.

The question I would like to pose is ‘what really happened during this rework?’ In the move from modernity to postmodernity, the focus has changed. Does this mean compromise? The change has happened in many forms, yet using the policy and attitudes towards ‘building’ in the two schools, we can evaluate them on a level playing field.

In my personal day to day experiences of the school, I have never been encouraged to ‘build something’. However, I have been encouraged to think reflectively, as if constructing something from thought. Within Itten’s original preliminary base course structure, the idea of elementarization[3] of basic artistic means plays a large part. I question wether this is still relevant with postmodernity. Elementarization was a method of finding the core of things. That could be related to shape, colour, and formal elements much better than thoughts, concept or theories. Deconstruction of colour, according to Itten’s book ‘The Elements of Colour’, allows you to provide “general rules and laws of colour, yet also relate it to subjective opinion”. Elementarization is a bid to find the root of something, the truth in which the experience lies. However, within a postmodern (Rietveld) structure, ‘truth’ itself is something shied away from. Instead of trying to find ‘the truth about colour (or making)’, we are left trying to find ‘the truth about thinking’, left ‘thinking about thinking’.

It is important to mention that even just through the existence of the Basic Year, and the formation of classes, teachers and subjects, it is apparent that the Rietveld does honour the idea of a ‘good education’, over a ‘bad one’. They have, after all applied this structure to the course based on reason and pedagogy[4] study (or so I would assume). Thus, the structure must be based on certain means that deem it useful or good to us as students. This leads me to believe that there is indeed a right and a wrong way to educate young artists. In other words, there is a true art education to be obtained. In the Gropius manifesto of 1919, ‘What is Architecture’, this truth lies in “architecture, painting and sculpture”. But the world today demands a wider spectrum of conversation. I personally think that it is more than okay to dedicate oneself to finding a real trade, or becoming the master of something, as opposed to a jack of all trades.

I can see both sides of the story in so much that The Rietveld has to keep up to date with the process’ of the current art world, but coming from a somewhat dated model. When beginning this essay, I was under the impression that the school was undergoing some kind of identity crisis. Attempting to link themselves to their withering ancestral roots in Bauhaus. I would argue that the link is indeed withering. That can be seen in their policies on ‘making’. It is perhaps more of a historical connection now. In truth, if I wanted to become a master woodworker, I could. But it wouldn’t line up with the philosophy of the school. I have personally received criticism for dedicating myself towards attempting to become a kind of master in one material.

In conclusion, Gropius himself would suggest that the Rietveld needs a re-work if we are to base our education on a Bauhausian model. I think he would suggest that there are no ‘master craftspeople’ being raised up.

The Rietveld Academie has not explicitly chosen to follow the Bauhaus manifesto like some kind of Bible, so, from the perspective of a student studying here now, the school is allowed to deviate from the original blueprints due to societal changes. I personally think it’s great that we aren’t all sold into unpaid labour making zig-zag chairs. Yet, the school should probably analyse its withering links to the past. Just like inevitably a grandson will probably have different interests to his Grandfather. The Rietveld is not in an identity crisis, but slowly developing the ability to keep proud the family name, yet not live in the shadow of it’s ancestry. There will probably be a time, when the Rietveld’s education model will bear no similarity at all with that of the Bauhaus.

[1] Modernism(ism) – Modernism refers to a global movement in society and culture that from the early decades of the twentieth century sought a new alignment with the experience and values of modern industrial life. These were often utopian, and modernism was in general associated with ideal visions of human life and society and a belief in progress.

[2] Postmodern(ism) -Postmodernism was a reaction against modernism. While modernism was based on idealism and reason, postmodernism was born of scepticism and a suspicion of reason. It challenged the notion that there are universal certainties or truths.

[3] Elementarization – The reduction of artistic elements to their most basic or original form.

[4] Pedagogy – The method and practice of teaching, especially as an academic subject or theoretical concept.

-

Johannes Itten, The Elements of Color, John Wiley and Sons Inc, Hoboken, 1970

-

CityLab. (2019). Western Pennsylvania’s Bauhaus Town. [online] Available at: https://www.citylab.com/design/2019/03/bauhaus-pennsylvania-gropius-breuer-aluminum-city-terrace/584485/ [Accessed 20 May 2019].

-

Moss, C. (2019). 100 years of Bauhaus: Berlin and beyond. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2019/mar/16/100-years-bauhaus-germany-berlin-weimar-dessau [Accessed 20 May 2019].

-

The New Bauhaus. (2019). The New Bauhaus. [online] Available at: https://www.thenewbauhaus.com/ [Accessed 20 May 2019].

-

Gropius, W. (1919). Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Manifesto (1919). [online] Adepratt.weebly.com. Available at: https://adepratt.weebly.com/uploads/3/7/7/1/37716215/bauhaus_-_manifesto__program_statement.pdf [Accessed 20 May 2019]

-

Bauhaus-imaginista.org. (2019). The Bauhaus Manifesto – Articles – bauhaus imaginista. [online] Available at: http://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/1771/bauhaus-manifesto-re-cap [Accessed 21 Apr. 2019]

-

Danchev, D., 2011. 100 Artists’ Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists. (s.n.). p159-p161 (M33 Walter Gropius – What is Architecture? 1919)

-

Gerrit Rietveld Academie. (2019). Home. [online] Available at: https://rietveldacademie.nl/ [Accessed 20 May 2019]