The project I singled out from the NAI treasure collection is called 15 MILES INTO THE EARTH by Hendrik Wijdeveld.

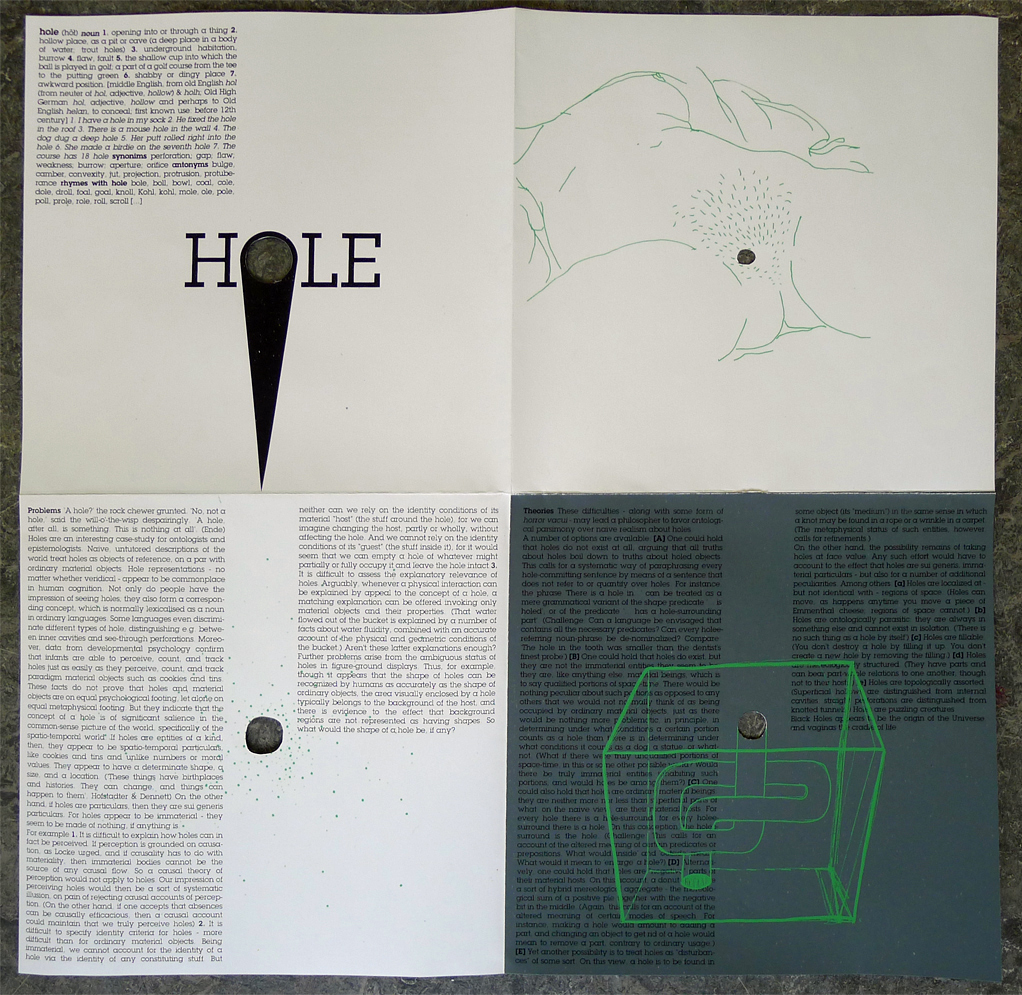

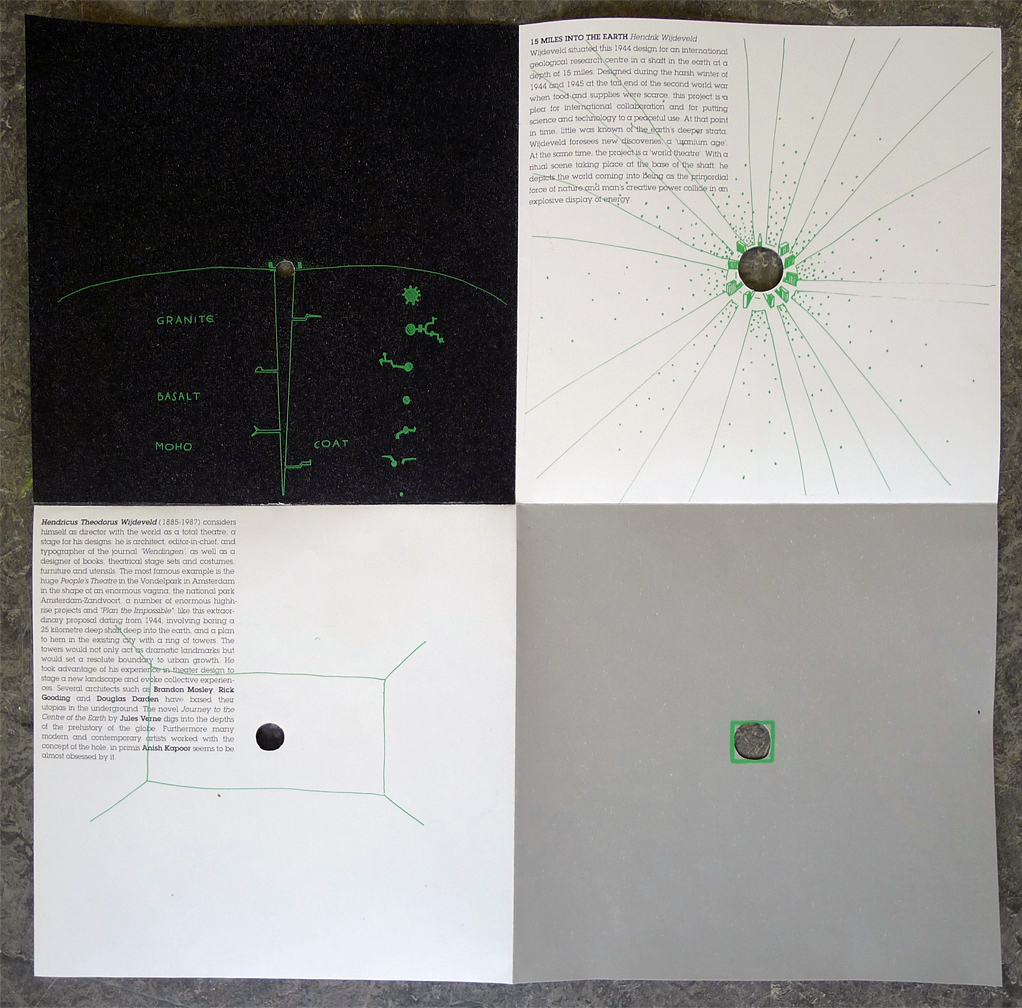

Wijdeveld situated his 1944 design for an international geological research centre in a shaft in the earth at a depth of 15 miles. Designed during the harsh winter of 1944 and 1945 at the tail end of the Second World War when food and supplies were scarce, this project is a plea for international collaboration and for putting science and technology to a peaceful use. At that point in time, little was known of the earth’s deeper strata. Wijdeveld foresaw new discoveries, an ‘uranium age’. At the same time, the project is a ‘world theater’. With a ritual scene taking place at the base of the shaft, he depicts the world coming into being as the primordial force of nature and man’s creative power collide in an explosive display of energy.

Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld (1885-1987) considers himself as director with the world as a total theatre, a stage for his designs: he is architect, editor-in-chief, and typographer of the journal ‘Wendingen’, as well as a designer of books, theatrical stage sets and costumes, furniture and utensils. The most famous example is the huge People’s Theatre in the Vondelpark in Amsterdam in the shape of an enormous vagina, the national park Amsterdam-Zandvoort, a number of enormous high-rise projects and “Plan the Impossible”, like this extraordinary proposal dating from 1944, involving boring a 25 kilometre deep shaft deep into the earth, and a plan to hem in the existing city with a ring of towers. The towers would not only act as dramatic landmarks but would set a resolute boundary to urban growth. He took advantage of his experience in theater design to stage a new landscape and evoke collective experiences.

Several architects such as Brandon Mosley, Rick Gooding and Douglas Darden have based their utopias in the underground. The novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth by Jules Verne digs into the depths of the prehistory of the globe. Furthermore many modern and contemporary artists worked with the concept of the hole, in primis Anish Kapoor seems to be almost obsessed by it.

hole (hõ?) noun 1. opening into or through a thing 2. hollow place, as a pit or cave (a deep place in a body of water; trout holes) 3. underground habitation, burrow 4. flaw, fault 5. the shallow cup into which the ball is played in golf; a part of a golf course from the tee to the putting green 6. shabby or dingy place 7. awkward position. [middle English, from old English hol (from neuter of hol, adjective, hollow) & holh; Old High German hol, adjective, hollow and perhaps to Old English helan, to conceal; first known use: before 12th century] 1. I have a hole in my sock 2. He fixed the hole in the roof 3. There is a mouse hole in the wall 4. The dog dug a deep hole 5. Her putt rolled right into the hole 6. She made a birdie on the seventh hole 7. The course has 18 hole synonims perforation; gap; flaw; weakness; burrow; aperture; orifice antonyms bulge, camber, convexity, jut, projection, protrusion, protuberance rhymes with hole bole, boll, bowl, coal, cole, dole, droll, foal, goal, knoll, Kohl, kohl, mole, ole, pole, poll, prole, role, roll, scroll […]

‘A hole?’ the rock chewer grunted. ‘No, not a hole,’ said the will-o’-the-wisp despairingly. ‘A hole, after all, is something. This is nothing at all’. (Ende)

Holes are an interesting case-study for ontologists and epistemologists. Naive, untutored descriptions of the world treat holes as objects of reference, on a par with ordinary material objects. Hole representations – no matter whether veridical – appear to be commonplace in human cognition. Not only do people have the impression of seeing holes; they also form a corresponding concept, which is normally lexicalised as a noun in ordinary languages. Some languages even discriminate different types of hole, distinguishing e.g. between inner cavities and see-through perforations. Moreover, data from developmental psychology confirm that infants are able to perceive, count, and track holes just as easily as they perceive, count, and track paradigm material objects such as cookies and tins. These facts do not prove that holes and material objects are on equal psychological footing, let alone on equal metaphysical footing. But they indicate that the concept of a hole is of significant salience in the common-sense picture of the world, specifically of the spatio-temporal world. If holes are entities of a kind, then, they appear to be spatio-temporal particulars, like cookies and tins and unlike numbers or moral values. They appear to have a determinate shape, a size, and a location. (‘These things have birthplaces and histories. They can change, and things can happen to them’, Hofstadter & Dennett) On the other hand, if holes are particulars, then they are sui generis particulars. For holes appear to be immaterial – they seem to be made of nothing, if anything is.

For example: 1. It is difficult to explain how holes can in fact be perceived. If perception is grounded on causation, as Locke urged, and if causality has to do with materiality, then immaterial bodies cannot be the source of any causal flow. So a causal theory of perception would not apply to holes. Our impression of perceiving holes would then be a sort of systematic illusion, on pain of rejecting causal accounts of perception. (On the other hand, if one accepts that absences can be causally efficacious, then a causal account could maintain that we truly perceive holes) 2. It is difficult to specify identity criteria for holes – more difficult than for ordinary material objects. Being immaterial, we cannot account for the identity of a hole via the identity of any constituting stuff. But neither can we rely on the identity conditions of its material “host” (the stuff around the hole), for we can imagine changing the host, partly or wholly, without affecting the hole. And we cannot rely on the identity conditions of its “guest” (the stuff inside it), for it would seem that we can empty a hole of whatever might partially or fully occupy it and leave the hole intact.3. It is difficult to assess the explanatory relevance of holes. Arguably, whenever a physical interaction can be explained by appeal to the concept of a hole, a matching explanation can be offered invoking only material objects and their properties. (That water flowed out of the bucket is explained by a number of facts about water fluidity, combined with an accurate account of the physical and geometric conditions of the bucket.) Aren’t these latter explanations enough? Further problems arise from the ambiguous status of holes in figure-ground displays. Thus, for example, though it appears that the shape of holes can be recognized by humans as accurately as the shape of ordinary objects, the area visually enclosed by a hole typically belongs to the background of the host, and there is evidence to the effect that background regions are not represented as having shapes. So what would the shape of a hole be, if any?

These difficulties – along with some form of horror vacui – may lead a philosopher to favor ontological parsimony over naive realism about holes.

A number of options are available: [A] One could hold that holes do not exist at all, arguing that all truths about holes boil down to truths about holed objects. This calls for a systematic way of paraphrasing every hole-committing sentence by means of a sentence that does not refer to or quantify over holes. For instance, the phrase ‘There is a hole in…’ can be treated as a mere grammatical variant of the shape predicate ‘… is holed’, or of the predicate ‘… has a hole-surrounding part’. (Challenge: Can a language be envisaged that contains all the necessary predicates? Can every hole-referring noun-phrase be de-nominalized? Compare: ‘The hole in the tooth was smaller than the dentist’s finest probe’) [B] One could hold that holes do exist, but they are not the immaterial entities they seem to be: they are, like anything else, material beings, which is to say qualified portions of space-time. There would be nothing peculiar about such portions as opposed to any others that we would not normally think of as being occupied by ordinary material objects, just as there would be nothing more problematic, in principle, in determining under what conditions a certain portion counts as a hole than there is in determining under what conditions it counts as a dog, a statue, or whatnot. (What if there were truly unqualified portions of space-time, in this or some other possible world? Would there be truly immaterial entities inhabiting such portions, and would holes be among them?) [C] One could also hold that holes are ordinary material beings: they are neither more nor less than superficial parts of what, on the naive view, are their material hosts. For every hole there is a hole-surround; for every hole-surround there is a hole. On this conception, the hole-surround is the hole. (Challenge: This calls for an account of the altered meaning of certain predicates or prepositions. What would ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ mean? What would it mean to ‘enlarge’ a hole?) [D] Alternatively, one could hold that holes are “negative” parts of their material hosts. On this account, a donut would be a sort of hybrid mereological aggregate – the mereological sum of a positive pie together with the negative bit in the middle. (Again, this calls for an account of the altered meaning of certain modes of speech. For instance, making a hole would amount to adding a part, and changing an object to get rid of a hole would mean to remove a part, contrary to ordinary usage.) [E] Yet another possibility is to treat holes as “disturbances” of some sort. On this view, a hole is to be found in some object (its “medium”) in the same sense in which a knot may be found in a rope or a wrinkle in a carpet. (The metaphysical status of such entities, however, calls for refinements.)

On the other hand, the possibility remains of taking holes at face value. Any such effort would have to account to the effect that holes are sui generis, immaterial particulars – but also for a number of additional peculiarities. Among others: [a] Holes are localized at – but not identical with – regions of space. (Holes can move, as happens anytime you move a piece of Emmenthal cheese; regions of space cannot.) [b] Holes are ontologically parasitic: they are always in something else and cannot exist in isolation. (‘There is no such thing as a hole by itself’) [c] Holes are fillable. (You don’t destroy a hole by filling it up. You don’t create a new hole by removing the filling.) [d] Holes are mereologically structured. (They have parts and can bear part-whole relations to one another, though not to their hosts.) [e] Holes are topologically assorted. (Superficial hollows are distinguished from internal cavities; straight perforations are distinguished from knotted tunnels.) Holes are puzzling creatures.

Black Holes appear to be the origin of the Universe, and vaginas the cradle of life.