• Even if you enjoy only one story, a daytrip to “Super Stories” in Hasselt [B] will have been a day wel spend.

Tugged away on the attick of an the old Jenever brewery museum I found such a story, on which Malin Bülow wrote this essay.

On Azart and the “linguistic relativity principle”

Have you ever pondered about why time is a line, why it is horizontal and not vertical, why future is ahead of you and history behind you?

A fundamental debate in cognitive sciences is the extent to which our language influences or constrains our perception. Benjamin Whorf quite radically argues that “we dissect nature along lines laid down by our native language”(1), meaning that language directly affects cognition, the way we think, how we look at things and experience reality. This way of thinking, referred to as the “linguistic relativity principle”, suggests that we can’t imagine things or events or anything else that does not have a corresponding word in our mental lexicon. Therefore our language influences the manner in which we understand reality and behaviors. Coming back to the initial pondering on our perception of time, the way we talk about time: “timeline”, “looking forward to tomorrow”, “ahead of time”, “behind schedule” etc, explains our cognitive reference of time being a two-dimensional horizontal line. The cognitive visualization of time is then secondary to the words describing time. One can say that our reality is trapped in words, physical letters, which forms and appearance are highly coincidental and not at all connected to the actuality they define. Quite an amount of studies on color perception (2,3), categorization (4,5) and numerical cognition (6) among others support this view.

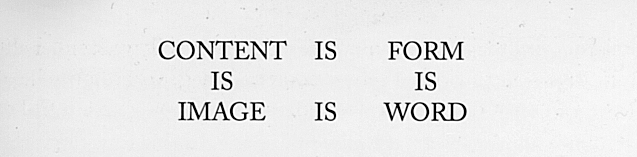

Guy Rombouts, (1940-, Geel, Belgium) seems to make a comment on how the flatness of letters and words can create a reality and make that reality non-existing without the words, in line with what the “linguistic relativity principle” suggests. Rombouts does this by inventing a new alphabet; the Azart, a name that refers to A-Z art, but also to the French word “hasard” meaning coincidence. In Azart each letter is translated by a corresponding line, on the basis of the first letter of the word which describes the line. A is angular, B is barred, C is curve, D is deviation and Z is a zigzag line. When the lines are linked together closed forms or word-images appear. What is going on quite literally on the paper when forming Azart words, goes on in our mind when forming realities of alphabetic words. The arbitrary letters of the alphabet also obtain meaning in our mind.

Words written in Azart visually define them selves, forming isles of meanings, while words of the alphabet is defined by means of other words. These words, however, are formed by the same letters as the word they define. A circle of definitions are formed, referring again literally to the Azart circled words.

Sources:

Cassiman, B. (1989). Guy Rombouts, Narcisse Tordoir. (Dublin: Douglas Hyde Gallery)

some other links: www.hanstheys.be/ (work, movies and interviews): La Paloma part 1 & 2 : SKOR (Art in the Public Space): De Appel (exhibition): Bridge (Java Isle Amsterdam): =vorm=word=image=content= : Guy Rombouts/Azart at Rietveld Designblog researches: at the MUHKA Antwerp: one final image~story……..

you can download this research by Malin Bülow: as a pdf