Her Previous Incarnation

Sunday, April 17, 2016

"Don't ask from where I have come,

My home is far, far away.

Why do you wander so far? Wander so far?"

- "Olive Tree" by Sanmao

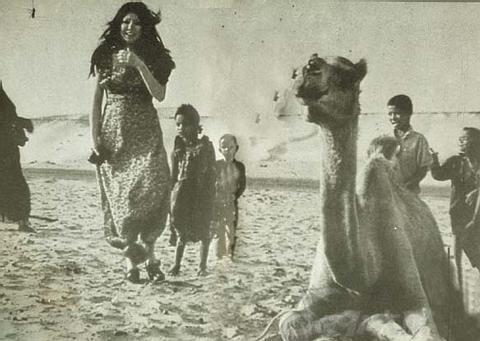

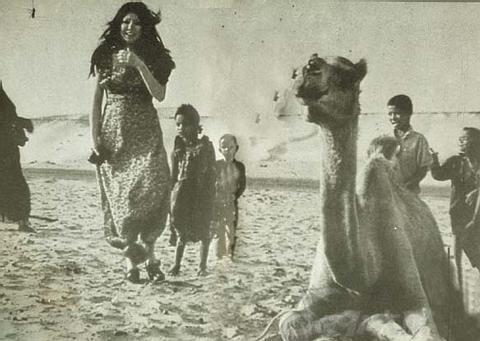

Sanmao to me was an incurable romantic, a lonely dreamer and a gifted drifter who had spent most of her life travelling and writing. The stories and the journals she wrote beautifully reflected the unforgettable journeys she undertook, the incredible places and people she had seen. Sanmao studied philosophy in Taiwan and continued her education later on in Spain and Germany. After her study and the tragical loss of her fiancé, Sanmao returned to Spain and there she made up her mind to follow the sunset of Sahara . Her life as a drifter and a writer then began.

I’ve always been very much moved and inspired by the stories of her life journey, as her writings didn’t only describe the wonderful experiences of her trips but also illustrated the difficult realities she had to deal with. (Here is one of her stories – “The Mute Slave” collected in the book “The Stories of Sahara”.) Because of her kindness and courage, she was able to prepare herself to face all the challenges and risks of her adventure. To me Sanmao’s writings mean much more than a travelogue, significantly they stand for her values of life. Therefore, I decided to take Sanmao as the person/source of my inspiration for this “Identity” design project.

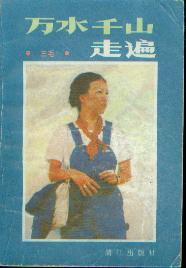

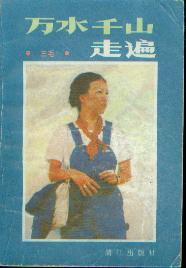

As I was quite familiar with her books, in her writings what interested me the most was her fascination with her previous incarnation. In the book “Wan Shui Qian Shan Zou Bian”, she wrote that she had always believed she was an Ecuadorian Indian girl in her last life. When she traveled to one remote village hidden in the Andes, she felt immensely connected to the highland, as if she had come back to the homeland of her previous life. As she wrote, in her last life she was a Cañari (“an indigenous ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the territory of the modern provinces of Azuay and Cañar in Ecuador”) girl named Hawa. The name Hawa in their language means heart. She was a pharmacist’s granddaughter who lived her entire life happily and peacefully in the village of the silver lake (also known as the lake of heart) till her death.

As her imaginary previous life fascinated me so much, I decided to design the headpiece based on her last life story and research on the indigenous inhabitants of Ecuador as a starting point. It was at first difficult to figure out the ethnicity of Hawa in English and there was no Chinese information regarding the ethnic group she belonged to. However, after several rounds of research on the history of the indigenous people of Ecuador, I was able to confirm that Hawa’s ethnicity was Cañari. Research on history, culture and custom of the Cañari was then further conducted.

Interestingly, I found the Cañari indians loved wearing hats. “Those of you who have been following our South American journey know how important, and ubiquitous, hats are to the people of the Andes. Fedoras are to be found everywhere, stovepipes are not uncommon, and the Cholas of Bolivia have turned blower hats into a jaunty fashion statement of national pride. Many wear straw hats, and in Ecuador at least, have them refurbished by painting them to make them last longer. I must also mention Panama hats, which are not from Panama at all, but are exclusively an Ecuadorian creation”, Alison and Don wrote in their post “The Cañari of Ecuador, a ‘palace’ and a pig”.

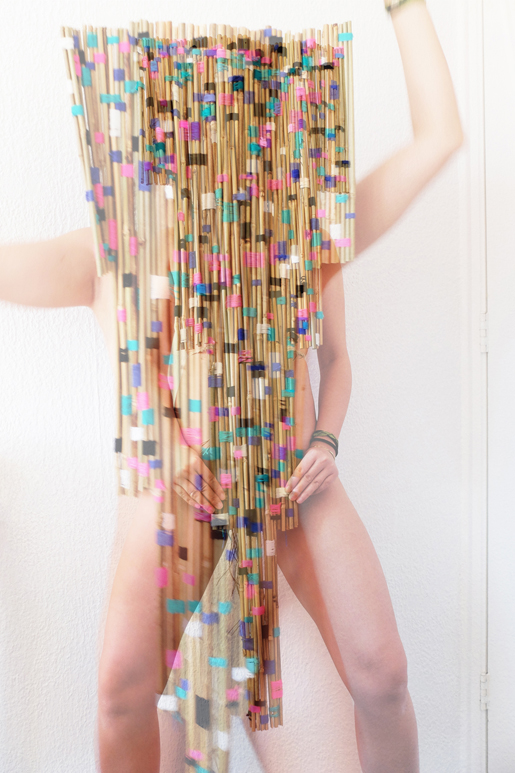

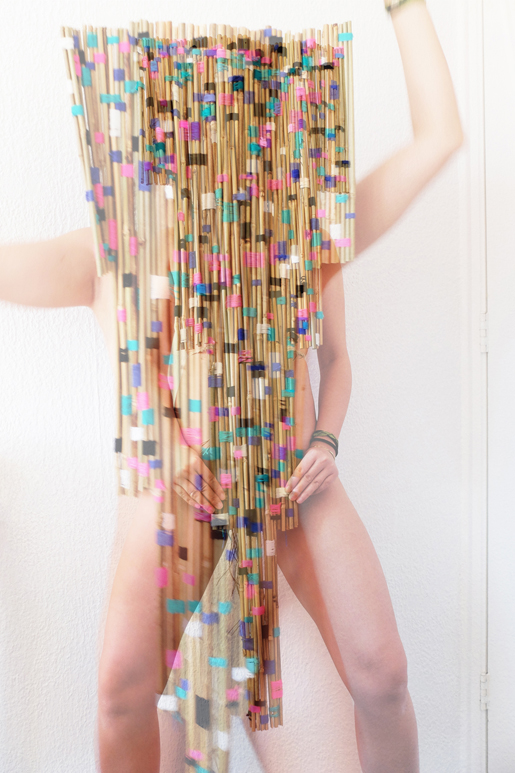

Nevertheless, among the different types of hats they wear, I found one kind that was particularly special. The hat is made with a wide brim and many strands of colourful yarns falling from the edge. The Cañaris usually wear it for festivals and celebrations.

On the other side of my research, I discovered the Cañaris created a very unique moon worshipping system using large rocks. “The Incas worshipped the sun, but the Cañaris worshipped the moon. There are 28 holes on the larger rock, one for each day in a lunar month. Each hole is drilled at a different angle and when water is added, the Cañaris would look at the reflection of the moon in the small pools. This was their way of receiving messages from their god. The other “holey rocks” were most likely used to hold paint (for painting faces, textiles, etc), “ Mellisajane14 wrote in her blog “Ingaprica: Incas in Ecuador”.

After a few rounds of research, I began to develop ideas for the design of the headpiece for Hawa. In the end I decided to make masks for her to wear, as I believed Hawa – the preexistence of San Mao should be a vague figure without revealing a clear face.

Meanwhile, inspired by those bright, colourful yarns and holy rocks, I planned to seek and experiment with similar and relevant materials so as to resemble the Cañari elements. Wood and bamboo were selected due to their primitiveness associated with the Cañari indians. Clay and small rocks were also applied, echoing those incredible rocks.

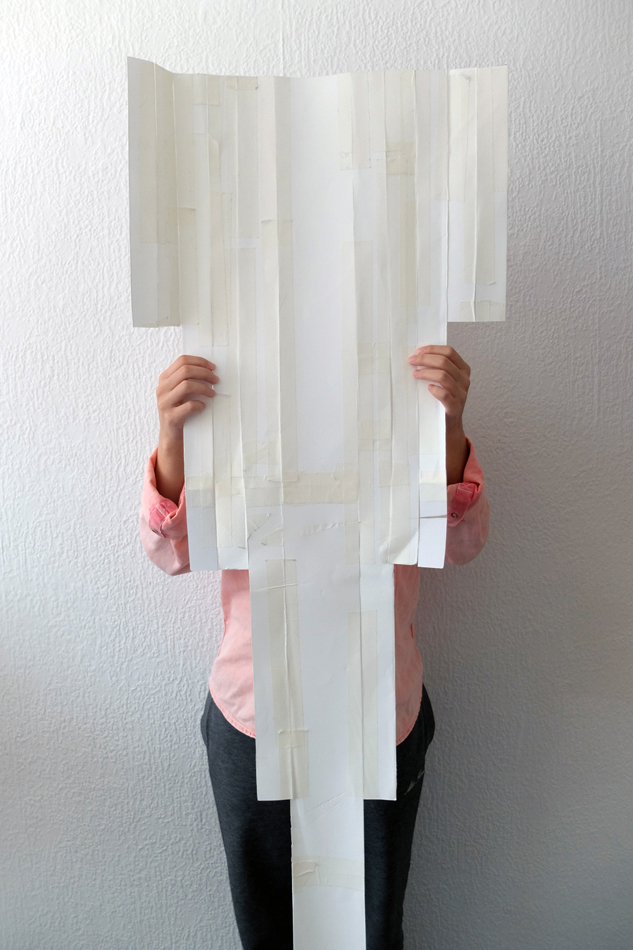

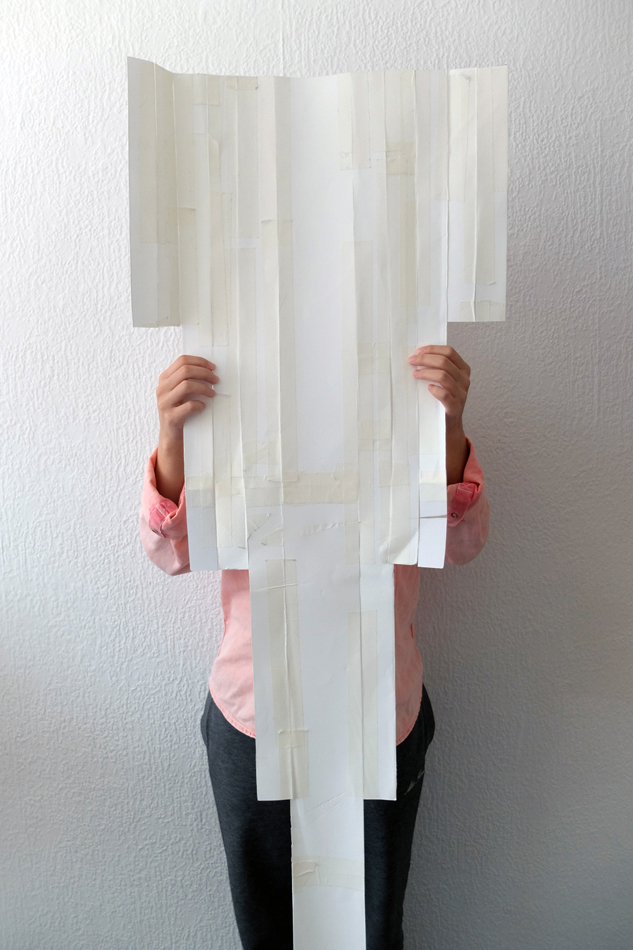

After the experimental trials with materials, a clearer image of the mask that I wanted to make gradually emerged. The try-outs with the clay mask as well as the small rocks didn’t turn out strong enough to mirror the Cañari moon worshipping system. However, the results of colourful yarns in combination with wood and bamboo were quite intriguing. Hence, I decided to further continue the mask concept mainly using yarn, bamboo and wood. As the techniques of applying yarns I developed during the experiments were different, I was suggested to make two masks using both techniques (yarn with wood and yarn with bamboo). In the first technique, long strands of yarn in selected colours were made and locked to an organic-shaped wooden stick that was found in the street, creating the idea of a mask that could cover most of the body. While in the other one, yarns were applied as components to bind the bamboo sticks.

As I discovered that yarn strands in volume and layers would turn out more visually powerful in the form of masks, and bamboo sticks bound with brightly coloured yarns placing vertically would create a refreshing effect. Therefore, I decided to continue working on the mask of yarn strands by creating more volume in layers. On the other hand, I tried to come up with a few scale models to explore the overall shape of the bamboo mask. I found that a mask of bamboo sticks in different lengths and a more or less geometric shape could be primitive and fit well in the Cañari vibe. I eventually chose one shape that I thought would connect to the story the best and made a paper mock-up of it.

Simultaneously, I kept working on the mask with layers of the yarn strands. In the initial plan, hemp rope was used to coin around both the ends of the wooden stick, building a vast contrast between the fineness of the yarn and roughness of the rope, while small gaps were left between the yarn and the rope for hair fixation, creating a way for Sanmao/Hawa to put the mask on. However, I discovered it would be even stronger to leave out the hemp rope and cover the rest of the wooden stick using only hair.

As for the bamboo mask, I continued building and finishing it according to the mock-up and came up with another means of fixation by attaching a few strands of straw rope to tie around Sanmao/Hawa’s body. The process of building was a bit struggling due to the difficulty of binding the slightly bended bamboo sticks.

Nevertheless, after two months of efforts, the masks were eventually finished. Although there were struggles and doubts, I was quite happy with the process as well as the results. After finishing the works, I decided to try them on for photo documentation. As you can see, the photos were taken in different settings. Wearing the colourful headpiece with the long yarn strands, I thought that it was necessary to feel the wind and frame the yarn flying moment at my balcony. I felt spiritual and being transformed into a shaman from an Andes tribe. It was incredible. When I firstly put on the bamboo mask, I felt the urge of being completely natural. I wore the bamboo mask naked and did some tribal dancing and humming in my room. I felt happy and free then. In the end, I decided to keep the pictures taken at the balcony original and fresh, while adding some effects to the photos of the bamboo mask, making it a bit strange and whimsical.

I’m certainly glad that my father introduced Sanmao’s books to me at my younger age, when talking about the relations between writing and experiences of life. Without her journeys, I believe that she couldn’t have told so many wonderful stories. And it definitely helped me to rediscover myself and to a certain extend shaped my view/values of life. To me life is a long journey after all. I made these two masks for her/ her previous incarnation in remembrance of her free spirit. These two masks carry special meanings to me, as they were made for Sanmao – an incurable romantic, a lonely dreamer and a gifted drifter who I feel deeply in common with.

Goodbye Sanmao.