"Readable or Legible" Category

Research David Keshavjee & Julien Tavelli

Sunday, March 6, 2011

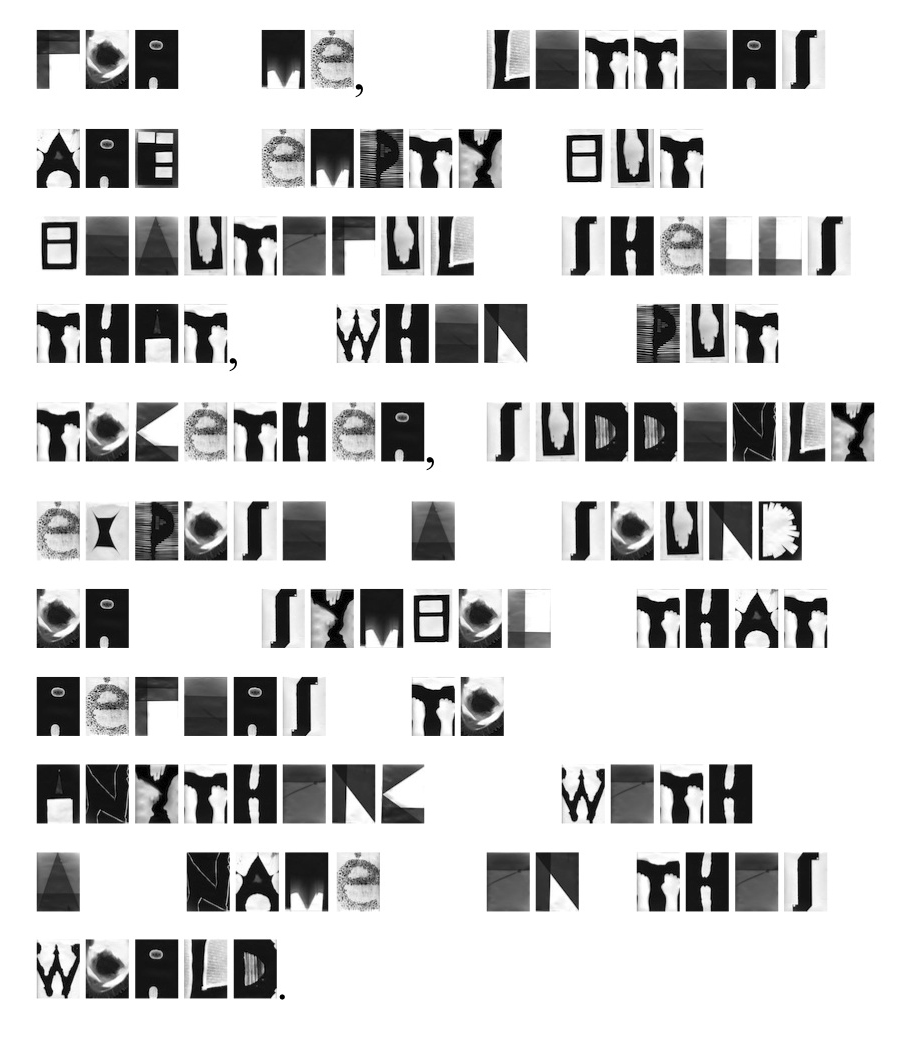

David Keshavjee (born 1985) and Julien Tavelli (born 1984) are two Swiss graphic designers/typographers, they both studied at Ecole Cantonale d’Art de Lausanne (ECAL) They where one of the winners of the Swiss Federal Design Award with their graduating project, ‘Using Tool,’ in 2009. They just made a pedagogic booklet at the Federal Office of Culture in New York, Acid Test. In collaboration with Körner Union and Tatiana Rihs they made offset cmyk experiments. Later they printed a reproduction of that handmade booklet, “Les impressions magiques“. They are part of Maximage Société Suisse, an exploration in the field of emotion and technology.

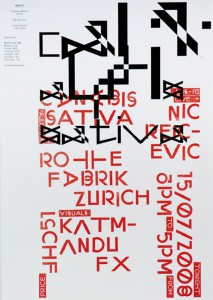

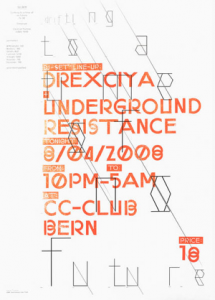

Their Using Tool project is, I think, the most interesting thing to discover about them, it explains a lot about how they work and how their poster series for music concerts where build up. The posters where published in Wallpaper and in the book ‘Typeface as Program,’ witch was published by Ecole Cantonale d’Art de Lausanne (ECAL) Especially the last one is very related to their process and what they are designing. They also explain in this book how Keshavjee and Tavelli approached their works by using half digital half manual tools during the process.

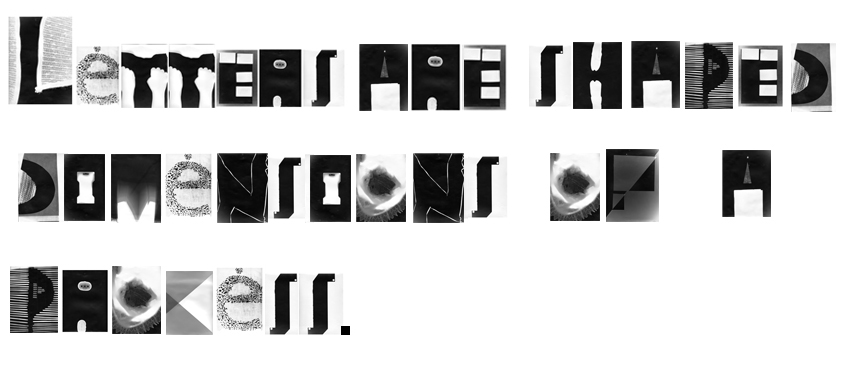

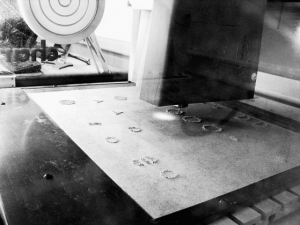

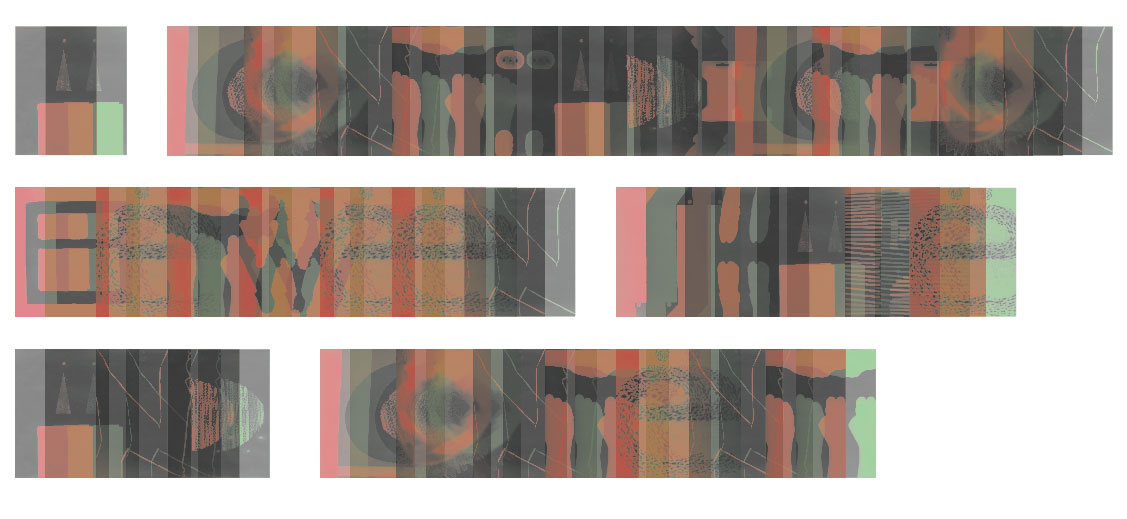

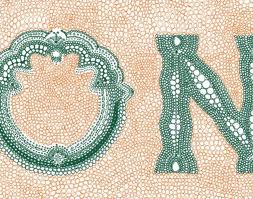

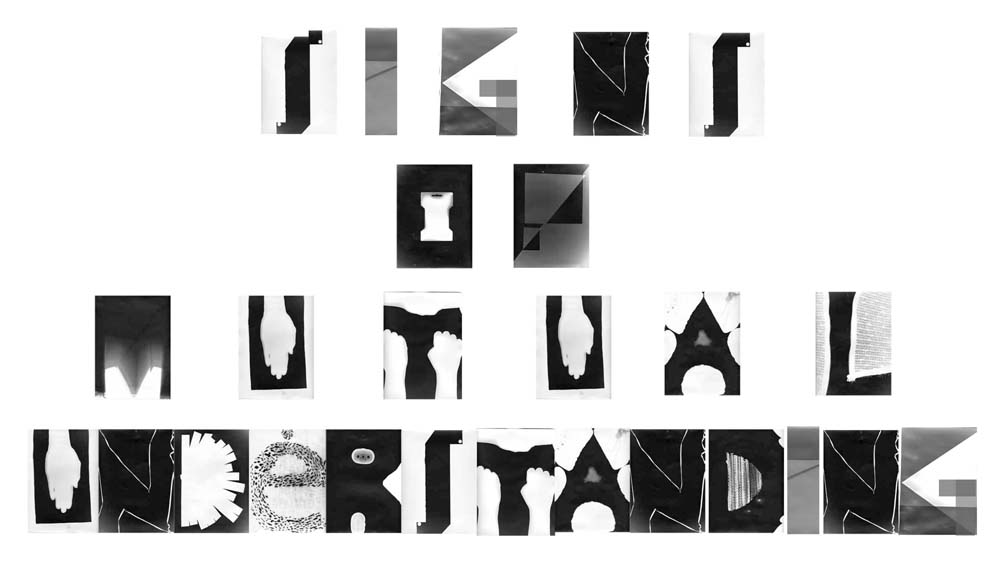

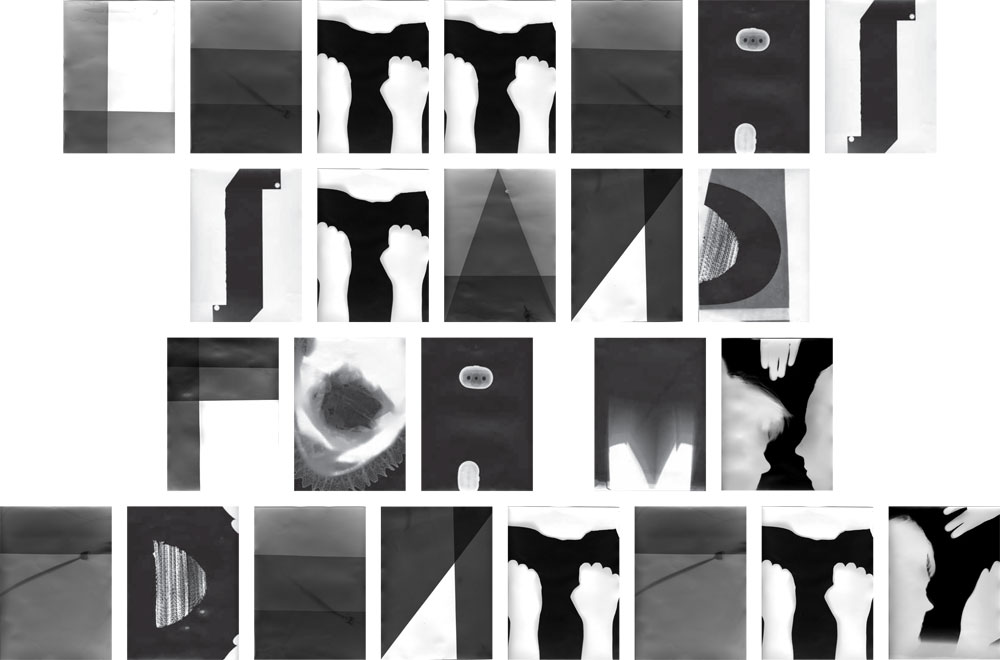

They started in their design process of the posters by first programming a script, inspired by a workshop of Frederik Berlaen on ECAL, that could automatically create a system of characters by using the already by Keshavjee and Tavelli designed ‘o’ and ‘n.’ Those two are the essence of the typeface, so with this characters the script is able to create the other characters of the alphabet. Keshavjee and Tavelli like to keep the random and uncertain factor in this system and in their font by giving the computer the control of the typeface. I think the script also helps them to design the first layer of the poster, the digital printed part, the black thin lines. When their computer created the characters they use a machine next to the computer that cut the letters out of a 2mm thin wooden plate what is still very raw then, but they do the final touch by hand. After they manufactured the wooden characters they cut pieces wood all the same size to glue the 2mm thin wooden characters on it. After they did this crucial step, they can think and work with the spacing of the letters, and build up the composition. The last step for them is to combine the background layer and the composition of the typography, the wooden characters into the final poster.

I think with the combination of manual and digital processes that are repeated at each step, from the production and application of the typography until in the composition and final print, Keshavjee and Tavelli create a refreshing and inspiring result of the raw woodcut with the smooth digital print. They work according to the principle that the means influence the form and that new forms of expression in graphic design can be created by combining different tools. These ideas are applied to the poster series as well, it’s the essence of their project. The posters are also published together with the thoughts about this series and an interview where they explain more in the book, ‘Typeface as Program.‘ There is also an interesting article on boston.com about the swiss designer thoughts of typography by Cate McQuaid.

For me they work a bit like typographic engineers I would say. They really are working with developing scripts and systems to help them approach typography in another way, not very usual and practical way, but an interesting one. You could think if you read about how controlled they work in a way, that they are probably to much controlling their work. But their prints are very open for unexpected accidents within its system, there is a lot that can go wrong, all trough this process the accidents are creating new opportunities in the creative process of their typographic experiments, that’s a good value of their work I think. They also always start projects by experiments. It could be interesting to learn and see more of the projects of David Keshavjee and Julian Tavelli, and see how they treat their project during the process of designing typography.

Hansje van Halem

Sunday, March 6, 2011

De computer heeft gezorgd voor drastische wijzigingen in de manier waarop lettertypes worden ontworpen en gebruikt. Het lag voor de hand dat grafische ontwerpers zouden reageren op de ontwikkelingen die hun traditionele manier van werken bedreigden. Ze ontwikkelden andere, soms ook traditionele, oplossingen voor de nieuwe weg naar de toekomst. Dit deden ze omdat ze bang waren dat mechanisatie tot een verdwijning van standaarden en gevestigde typografische regels zou leidden.

Tegenwoordig integreren veel belangrijke grafisch ontwerpers typografie, belettering en beeldproductie, waardoor ze meer opschuiven in de richting van de beeldende kunst dan in die van de vormgeving. Microsoft kwam in 1996 met het “Core fonts for the Web-project”. Microsoft wilde hiermee een standard set lettertypes gratis verspreiden. Deze lettertypes moesten goed leesbaar zijn op het sherm, verschillende stijlen bieden en ook geschikt zijn voor internationaal gebruik. Uiteindelijk zijn de volgende lettertypen hiervoor gekozen: Andale Mono, Arial, Comic Sans MS, Courier New, Georgia, Impact, Times New Roman, Trebuchet MS, Verdana en Webdings.

Dit zijn nog steeds de meest gebruikte fonts op het web. Bovengenoemde lettertypes zijn natuurlijk ontworpen om een tekst makkelijk leesbaar te maken, zodat je als lezer snel informatie kunt opnemen. Maar niet alleen handige fonts worden ontworpen. Er is namelijk ook behoefte aan sierletters, of aan letters die interesse wekken en waarnaar je aandacht getrokken wordt. Deze letters kunnen goed gebruikt worden op bijvoorbeeld posters.

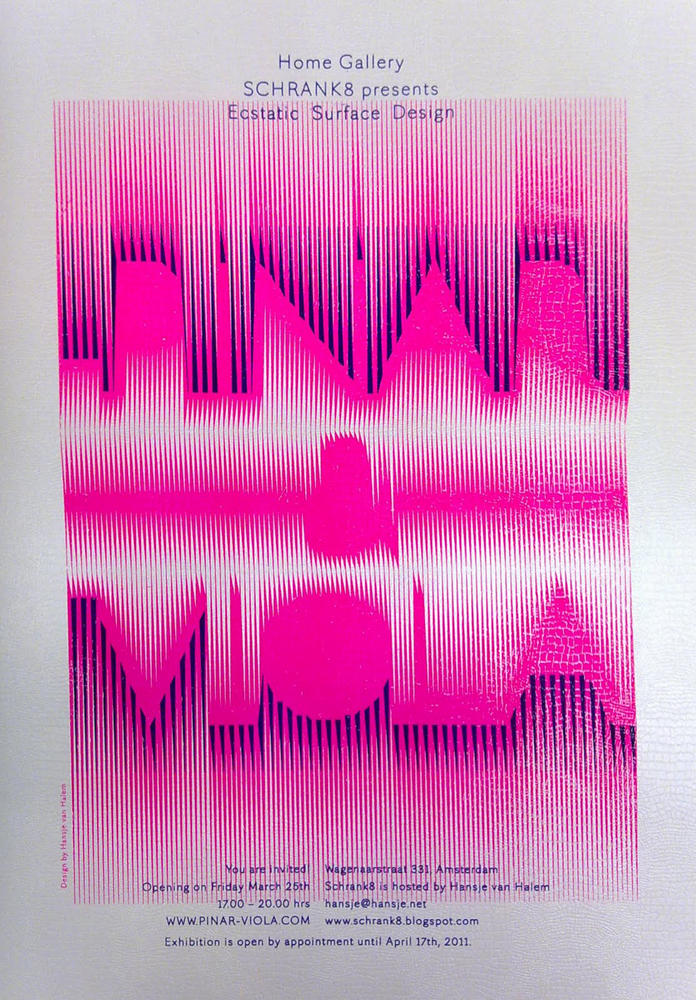

Een voorbeeld van een ontwerper van sierlijke letters is Hansje van Halem. Zij is afgestudeerd aan de Rietveld Academie afdeling grafisch ontwerpen met een vorm van typografie in het jaar 2003. Ondertussen heeft ze nog een aantal letters ontworpen, maar ze richt zich tegenwoordig vooral op het vormgeven van boeken en ontwerpen van patronen.

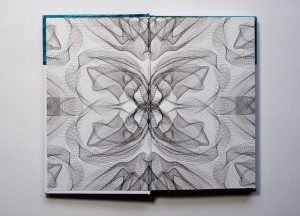

Sommige van haar ontworpen letters zijn ontstaan in opdrachtverband, of tijdens het tekenen van hun plek binnen een andere opdracht. Het afstudeerproject is een alfabet, opgebouwd uit een x-aantal lagen geschetste letters. Ze nam het frame van de letters van een al bestaand lettertype en tekende vervolgens deze letter daarin op de computer. Door een aantal lagen te kiezen is het mogelijk om heel precies te zijn met de dikte van de letter. Dit maakt het erg interessant, want zo kan het er telkens weer uniek uitzien door te spelen met de aantal lagen. Dit font is de enige die ze als totaal alfabet heeft ontworpen.

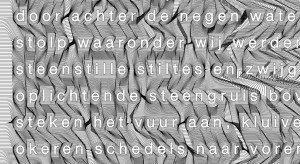

Verder heeft ze eigen ontworpen letters gebruikt voor posters of boeken, maar hiervoor alleen de letters getekend die ze nodig had. In deze voorbeelden komt ook meer haar algemene stijl naar voren dan bij haar afstudeerproject. Bij het zien van haar werk, is het duidelijk dat ze onder andere inspiratie bij ouderwetse technieken vind, zoals breien en kantklossen. In haar ontwerpen werkt ze niet zo zeer aan de vorm van de letter, maar meer met de invulling. Ze gebruikt bestaande letters en “tast” die vervolgens aan door middel van een systeem of regels die ze zelf bedenkt. Hansje van Halem gebruikt voornamelijk lijnen in haar werk. Dit doet ze, omdat ze op deze manier makkelijk met zwart en wit grijswaarden kan bepalen. Er is een constante spanning tussen dikte, schaal, structuur en handschrift. Door de computer is het mogelijk om met haar systemen ervoor te zorgen dat er geen onregelmatigheden ontstaan, maar juist dat vind ze erg interessant. Hierom gebruikt ze vaak kleine tekens van oneffenheden, verloop, zichtbare vermoeidheid en ontwikkeling en zorgt ervoor dat het nog een extra laag krijgt, wat de aandacht van de lezer langer vasthoudt.

Naast haar interessante afstudeerproject heeft ze onder andere ook het ontwerp gemaakt voor de Nederlandse postzegels van 44 cent en 88 cent. Bij de zegel van 88 cent heeft ze de cijfers zelf ontworpen en de tekst in het lettertype “Spectrum” erbij gezet. De ronde vormen van de achten komen terug in de kleine tekst eronder. Bij de postzegel van vierenveertig cent is het lettertype “Johnston” gebruikt. Het patroon op de achtergrond van beide zegels heeft ze ook zelf ontworpen. Deze zorgen ervoor dat de speelse, schijnbaar met de hand getekende cijfers toch een zakelijk/serieus uiterlijk hebben. Later heeft ze ook de aanpassingen gemaakt naar de nieuwe 1 en 2 zegel. Vooral de toegevoegde kleuren vallen daar in op

De letters van Hansje van Halem zijn sierlijk en interessant. Kleine krabbeltjes maken een letter gedetailleerd, maar storen de eesbaarheid niet. Soms is het zaak een moment te focussen om te ontdekken hoe de letter werkt, hoe het is opgebouwd, anderen laten duidelijk een systeem zien. In ieder geval is de concentratie en een passie voor ontwerpen in elk ontwerp terug te vinden.

Meer voorbeelden van het werk van Hansje van Halem en ook de periodieke tentoonstellingen die ze organiseerd met mede kunstenaars en

ontwerpers in haar huiskamer SCHRANK8  kun je bekijken op haar site

kun je bekijken op haar site

monospaced

Saturday, March 5, 2011

Monospaced Fonts.

The horizontal space that a letter occupies in a monospaced font is the same for every letter.

Meaning that wider letters are cramped into a smaller space, and thinner letters have more white space around them, so they will all fit in the same box.

Monospacing first occurred when the typewriter was invented, because the typewriter had to use the same space for every letter, a good example can be found in WordPad on Windows the standard font is still monospaced.

When looking at the shapes of letters it’s not hard to see that some letters need more horizontal space because they are more complicated in their shape, compare for instance the letter ‘m’ to the ‘i’ it seems obvious that the letter ‘m’ needs more space because it has 3 vertical lines opposed to one in the ‘i’, when these two letters need to be fitted into the same width then the ’m’ has to be cramped and the ‘I’ stretched, or the white space around it needs to be wider.

Is monospacing more easy and clear then variable-width fonts?

When seeing a monospaced font it immediately reminds me of old fashioned computers or typewriters, and it does not have any ‘flow’.

Most people will assume that the subject of the text corresponds with the typeface, making a text that is written monospaced unattractive for many people. Writing monospaced does give a certain structure to a text , although I doubt if it would become more clear, because it does more justice to the personality of a letter to give it the space that it needs and deserves, then to force it into a pre-defined space.

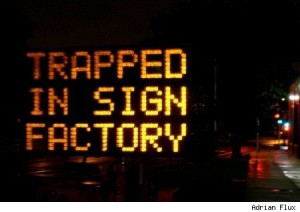

Using a monospaced font can serve some particular purposes, for instance when a text on a sign needs to be changed it is easier to work with when it’s possible to predict if a sentence fits when all letters have the same width, the same goes for some type of documents and other formal writings.

Concerning monospaced fonts it seems that technological reasons are more important than readability, although in bringing across a quick message they could work well.

Monospaced fonts can be strong when communicating short messages, but because it doesn’t ‘flow’ as nice as variable spaced fonts it can be more tiring to read long tekst written in monospace, because the words don’t become words but remain more separate letters.

What is important for readability of text is how letters form words when they are combined and here the white space in between is as crucial as the individual letter, monospaced fonts eliminate these characteristics and therefore it can take more effort to read a long text in a monospaced font.

In a monospaced font the letters have equal space, but why would an I or J or L need the same space as letters like W and M ?

If letters get the amount of space that they need instead of the amount that a technology allows them to have they can function more strong because they keep their own

characteristics, this way words can function as words instead of a combination of letters.

Why use monospaced fonts? I found out is mainly because of technological limitations, and in some cases to make it easier to know whether a text fits into a frame, although it seems there are more reasons to not use monospaced fonts but instead variable width fonts, because the main reason of text is communication and readability and they are stronger in variable width fonts.

Bob Vos

references:

list of monospaced fonts and a description.

http://www.fontsquirrel.com/fonts/list/style/Monospaced

this website contains many examples of monospaced fonts.

http://www.quora.com/Why-is-it-important-to-have-a-monospace-font-in-a-text-editor

text explanation about why monospaced fonts are used.

New eyes

Friday, March 4, 2011

Looking back in time, trying to remember how I’ve learned to write and read, no memories appears. At least no memories that create a clear image of the learning process.

In elementary school we learned the letters. We learned how they look like, how they sound, how to write them and connect them into words. This process took quite long time I think and it’s difficult to be described in retrospect. In these classes, we all had to study on writing the same letters, but we all created different handwriting. Some could do it beautifully, some ugly to unreadable. How a handwriting can be unreadable?

Now, reading a ‘small’ book from a ‘big’ man – Gerrit Noordzij, helps me to realize why and how I can do this today. A book written even before I was born answers the question as simple as ‘the space’ and with writing especially the ‘white space’.

In our current time we see hundreds of images every day. Some we remember for a reason, some we forget immediately. How does our human brain read those images? What helps it in this process?

The “boom” of a new ways to process images started in the second half of the 19th century, when people started creating more spaces for museums and galleries. Later on with the use of architectural deconstructions, making them fairly big and “clean”, with the only purpose to contain some of those special images for us.

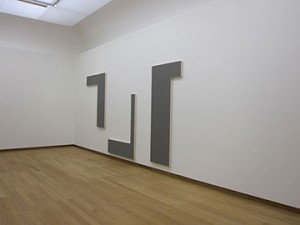

The use of space is very common in modern art. In some cases we actually perceive the space as a piece of the art. For example, if a work of art is placed in surrounding A, which is empty, it will be processed in your mind differently than in surrounding B, which is full with other objects.

In modern art we refer to surrounding A as the ‘White cube’, with its square or oblong shape, white walls and a light usually coming from the ceiling. A book from Brian O’Doherty (Inside the white cube – 1976), in which he confronted the modernist obsession with the white cube arguing that every object became almost sacred inside it, making the reading of art problematic.

As surrounding B was more standard in the few centuries before that. Then the exhibition space was the salon, a dark space so filled with works that it was difficult to see the beautiful, detailed paintings.

The importance of space can be found in different forms. Also in writing it plays a crucial roll in getting the message across, in other words: reading. In his book ‘ The stroke of the pen’ Gerrit Noordzij emphasise how the space in and around letters can make or brake the word and therefore the text.This space has to be put in rhythm. He writes: “The rhythmic connection of the white shapes in the word is the condition of the rhythm of the black shapes and vice versa.”

So this rhythm can be seen only in combination of letters. If a letter and subsequently a word doesn’t have its own space in and around it, then the white cube that belongs to the letter is impaired. As a result the word becomes just like an image hanging in saloon from 18 century.

Trying to understand this theory is like learning to read and write all over again. That opens a new perception on all written letters and words, how are they made and how they come across. Always look around and you’ll might see things in a new way…

We love geometry

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

Geometry appeals to us. When I was very young, I remember playing with wooden squares, circles and triangles, trying to find the right hole for them. Apparently, we learn to recognize geometry’s basic shapes from an early age. Not only is it one of the oldest mathematical sciences, it provides practical knowledge to interpret size, volume and relative position of figures in all kinds of situations. Through the axioms of geometry, measurements can be reduced to a simple set of lines, making our world a very synoptic place and providing us with a feeling of – why not – security and intelligent understanding.