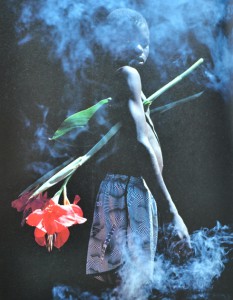

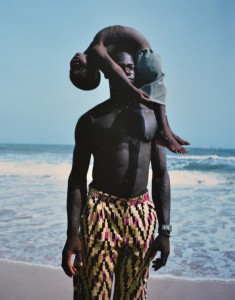

Viviane Sassen photographs people. But she doesn’t consider her photographs as portraits. Her models are more composition than persons. They are never photographed in close-up: it is always a total or semi total scene in which they figure. She almost uses her models as sculptures. Bodies always have a very sculptural aspect. She underlines that with very contrasted pictures. The faces of Sassen’s character’s are often no more than suggestions. They are surfaces and contours, black holes that contrast sharply with the bright, colorful surroundings. She uses a technique that could be called “the revered Clair-obscur”. While Rembrandt and Caravaggio used the light of a candle or their characters to emerge from dark decors, Sassen drapes a veil across the face. A tree, the edge of a roof, bystanders of whom only the legs are visible – they suggest eyes, mouth and nose with the echo of their presence.

Sassen makes 3 kinds of photographs: recumbent figures, lying with their head turned away from the viewer; intertwined bodies; and “Mystified portrait”: individuals who cannot be identified as such, who avert the camera’s gaze, who have a plant or a shadow of a plant where you expect a smile or a frown.

Between the age of 2 and 5 Sassen lived in a village in Kenya. It was a world of skinned goats’ head on market stalls, morning dew on the red earth, and sweet soft drinks in glass bottles and the smell of burnt charcoal. Her father worked in a hospital, and she herself played with the young patients from the polio clinic next door to their house. For a child of that age, who has not yet made the distinction between I and the other, the identification is complete.

She left Africa quite young and only came back there with a camera in 2001. During this in-between period, she flirted with the profession of fashion designer and became acquainted with photography. She sucked up the work of Araki, Nan Goldin, Thomas Ruff, Andres Serrano and Wolfgang Tillmans. Besides her autonomous work, she worked on assignment for progressive fashion labels like Miu Miu, Viktor & Rolf, Diesel, So, Adidas and Stella McCartney.

It is tempting to give an autobiographical interpretation to the images of her African’s work. But that would be too easy, opening the doors to accusations of navel-gazing and narcissism. “I’m attempting to recreate the images of my youth”, she says. But because of a lack of precisely determined locations these images have a universal charge, transcending personal ups and downs. And there’s a particular, political meaning behind them.

Sassen avoids all the stereotypes of Africa (bone-dry savannas with elephants and herds of zebras, or starving children with distended bellies) by focusing on the normal, the everyday. She then adds to this a strong dose of her own fantasy and memories.The difference between Sassen and her African colleagues is that they opt for a form of direct evocation, giving an explicit face to this seldom shown part of the world. Sassen’s work is much more implicit. She shows what it means to live in the pressure of African urbanization, the gulf between poor and rich, the contrast between black and white, the aftershocks of colonialism, the impact of HIV/AIDS. They are all hidden in the photographs, not immediately apparent but as an atmosphere. Sassen leaves space for the viewer to construct his own story.

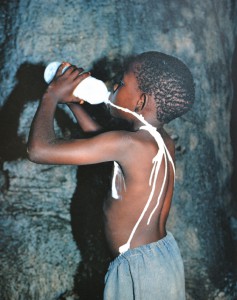

There is a strong evolution in the way she does that. In her earliest African work, the Cape Flats series from 2002 in South Africa, she works in a fairly documentary manner. These images are very factual, made with a sharp eye that ensures that the viewer is drawn into the image. In the series Flamboya made in East Africa between 2003 and 2006, the directing hand of the photographer is more evident: the pictures are more constructed and there is the continuous promise of a story (e.g the boy drinking milk from a bottle, the liquid flowing like rivers over the dark landscape of his back). In her series made in Ghana in 2007 entitled Ultra Violet, Sassen pushes her work method to the extreme, even working with members of a theater group from Accra. The poses are extreme, almost surreal. Sassen manipulates the malleable part of the reality she encounters and adds extra layers to this. We can see this particularly well with Rubedo (the red-painting girl busy, concentrating on her mobile phone). This picture evokes very strongly the contrasts poor versus rich, the old slow Africa versus the new fast generation, the proud yet vulnerable femininity versus tough but unbending masculinity, the mystery of animistic ritual versus the rationalism of the machine. The redness of her skin, moreover, evokes numerous associations (passion, AIDS).

By working in a visual idiom that falls outside the stereotypes, she questions the viewer’s gaze, particularly that of Western viewers. What images of Africa do we actually have and why? Why do we have no idea of what an ordinary shopping street in Cameroon looks like, a birthday party in Chad or a classroom in Gabon?

Sassen herself is aware that she has no moral safe conduct in this. A white person wandering around in Kenya, Ghana or Zambia has, whether they want it or not, a dominant position. The only thing that stand between her and a tourist is her intention. And nothing is more difficult to make clear than this. Where does interest end and exploitation begin? Sassen’s solution to this ethical dilemma is a particularly intensive collaboration with her models, bordering on co-authorship. The chemistry of an image has to be built up slowly, taking lots of polaroids before the final result, requiring effort from all the parties involved. This is all very different from Carter-Bresson’s “decisive moment”.

Sassen does not call herself a fashion photographer, nor an artist. She moves between a white and a black world. She accuses, but also listens. And somewhere along the lines her photography is born. In the shadow that is always there but never lets itself be fully captured.