Why do we build walls, roofs, doors? The same reason we build fires, run air conditioners, blow fans, humidifiers and de-humidifiers: to define and bend the atmosphere to our will. Once it is contained within walls, we change our atmosphere to the conditions we find to be the most pleasing, the most conducive to our continued growth & existence. In a cold place, the walls protect us from certain death at the hands of the wind & the freezing air. But what does the house do but capture the frozen air all around & tame it, domesticate it, as one would a wild animal, with constant care & attention? Human survival nearly everywhere on earth depends on this task.

Keeping air is like keeping the sea–it is all flow and energy, and everything we do to one part of it affects it all, creates a wave of reaction, for air resembles water in its motion: its currents and waves are wind, its warmth and chill move atom by atom up or down, each molecule making way for another as the others make way for it. How do we learn to use the qualities of this substance to our advantage, instead of treating it as something that happens to be there, an inconvenience, a battle to be fought with radiators and air conditioners? We know that this void is no void but a thin liquid in which we swim. Inside and outside, this air-thing called “climate” has finally found a place in the modern imagination, something that has its own identity, something that changes, that must be “saved”, and now that we recognize it, it is necessary to take it into consideration as we continue to build, as we continue to exist and grow.

Philippe Rahm is in some sense an activist for the interior climate, for finding an integrated way to use and not waste the nature of air and to revolutionize the way that we would constrain and encourage its flow with architecture. His focus is not the efficiency of the building for ‘the greater good’, however; he redefines how interior space is conceptualized in order to create a new language of architecture, one that can be equally bent to the need of function, efficiency and art.

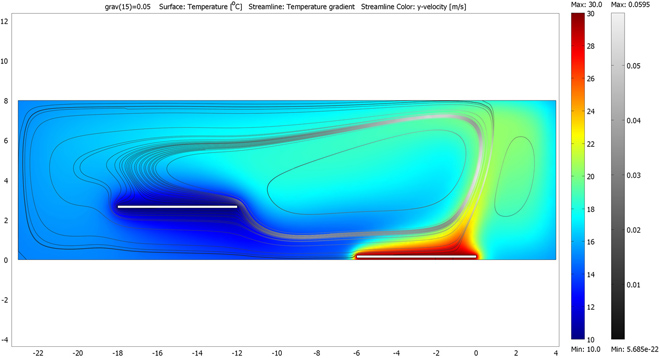

His “Digestible Gulf Stream”, a series of projects begun as an installation for the 2008 Venice Architecture Biennale, is a prime example of this language in use. As opposed to heating or cooling the different spaces in the structure to the optimal temperature for their use (warmer in the bathroom and living room, cooler in the stairways and bedroom), he uses the principles of thermodynamics to create a convection current that is perpetually cycling, aided by the structure of the space and two radiators that are set at a difference of 16 degrees Celsius. The function of the different areas of the house is thus prescribed by their place in this current as much as by their trappings. This is not a new idea, of course, but what is new (at least to this writer) iis the sense that there is a continuity, instead of merely a radiating outward of heat, from cold to warm, or vice versa.

This cyclic flow of air and energy implies an efficiency that is currently being used in sustainable architecture (as well as many traditional types of architecture that are not reliant on central heating and cooling), but with the sun as the warming influence and the shaded area to the north of a building as the cooling influence. The Earthship design concept has been around since the 1970s, and other practices in sustainable architecture and living–using recycled and recyclable materials and determining the form of the building by how to best use the natural forces available in the area, among many others–have been being implemented for millennia. In the industrialized world, however, these considerations have mostly only used as guiding architectural forces by the “hippie” community, but in a very practical way they speak to the same concerns and techniques that Mr. Rahm uses to an expressive end. They both assert the necessity of involving the atmosphere that we capture in our houses in the architecture, involving the living with the rules and patterns of the natural world instead of attempting to deny or fight them.

The concept that nature is a force opposite to the interests of humankind is, to all modern sensibilities, a very dated idea. It is an idea brought on by the industrial revolution, colonialism, an us-vs.-them mentality, one that as the world progresses past fossil fuels, past the ‘civilized man civilizing the savage’, past the need to explore (read: conquer) the unknown and remake it in our own image, we find of less and less value. To see the world as irrevocably “other” is to assume that we are not connected to it, that it is in some sense infinite, & time and technology have taught us that the world is a much smaller place than we think. We must throw our lot in with the trees and the fishes & all the other peoples of the world, because we are all connected and it will be a delicate balance that we strike, if we can strike it at all.

This emphatic need is being recognized in modern architecture and design, characterized by the so-called “green” movements of Slow Design (in the image of Carlo Petrini’s Slow Food movement) and sustainable architecture. Again, though, much of this design is based on a desire to make something that works in the best way, the most efficiently or the most cleanly. Philippe Rahm, although first an architect, is among those who recognize this need as an opportunity to create a new and subtle artistic medium, the chance to bend the very air around us to the task of expressing the human experience.